1733 Maintenance and sustenance

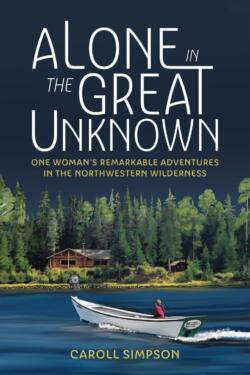

Alone in the Great Unknown: One Woman’s Remarkable Adventures in the Northwestern Wilderness

by Caroll Simpson

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2022

$26.95 / 9781550179941

Reviewed by Catherine Owen

*

As I load birch logs a local woodsman has chopped into my wood pit bin, groaning slightly at the work in only minus three conditions, I think about this book and feel ashamed. Narratives of wilderness survival on a range of levels, from Cheryl Strayed’s real life memoir Wild to Cormac McCarthy’s imagined post-apocalyptic novel of endurance amid perils known as The Road, all feature such incredible accounts of persistence against insane weather, brutish beasts, human encroachments and the basic and relentless demands made by the need for shelter, food and other essentials that one remains utterly astonished, and, at times, appalled. Caroll Simpson’s tale of buying a fishing lodge on Babine Lake, BC, dealing with her husband’s death only eighteen months later, and yet continuing the fight to thrive (for nearly a decade on a solo basis) in such an exquisite, dangerous land is a prime example of this genre.

As I load birch logs a local woodsman has chopped into my wood pit bin, groaning slightly at the work in only minus three conditions, I think about this book and feel ashamed. Narratives of wilderness survival on a range of levels, from Cheryl Strayed’s real life memoir Wild to Cormac McCarthy’s imagined post-apocalyptic novel of endurance amid perils known as The Road, all feature such incredible accounts of persistence against insane weather, brutish beasts, human encroachments and the basic and relentless demands made by the need for shelter, food and other essentials that one remains utterly astonished, and, at times, appalled. Caroll Simpson’s tale of buying a fishing lodge on Babine Lake, BC, dealing with her husband’s death only eighteen months later, and yet continuing the fight to thrive (for nearly a decade on a solo basis) in such an exquisite, dangerous land is a prime example of this genre.

The book is divided into five parts, with the first, “The Dream,” recounting the eighteen months Caroll lived at Ookpik Lodge with her husband David. Buying it off a couple who were forced to sell due to injury, the two were at first slightly naïve about the struggles that would ensue. Beauty can fool one. Simpson includes a plethora of description throughout detailing the gorgeousness of everything from sunsets to birds to trees, her depictions both glorious and irksome at times when clichés abound: pristine shorelines, the lake “smooth as glass,” heavens on earth, scampering squirrels, beautiful rainbows, soaring eagles, or sentences like “summer consumed us with its grandeur and was a precious reward.” The writing tightens up (though is inconsistently edited, especially numerically-speaking) when she recounts the wealth of activities required to sustain this existence, from splitting wood and maintaining boats, to schlepping provisions, to painting the cabins and, later on, hosting the variety of guests who come to stay with Caroll to dine on one of her fantastic meals (“candied yams topped with marshmallows and ginger … braided rosemary bread”) and to fish in the unnamed lakes. Throughout the earlier parts of the narration, after David’s unexpected death at 47, Simpson’s grief is filtered through this pell-mell of maintenance and sustenance.

When she adds being a forest defender, along with camp cook, grocery worker and later bridge guarder, to the list of jobs she must pursue to financially and ethically preserve her way of life and the natural world surrounding her, the story becomes even more incredible. And when you read of her torturous wrangles with black flies, grizzlies, bats, moose and most rupturously, the pine marten, an animal (times six of them!) who literally ravage her home, leaving “a frozen whirlwind of chaos,” necessitating Simpson’s ingenuity, fierceness and eventual death methods from shotgun blasts to bathtub drowning attempts, one is flabbergasted. These parts simmer with ferocious tension, akin to scenes in the film, The Revenant, where one frequently gasps in horror-wracked shock, wondering how the protagonist will ever escape “nature red in tooth and claw.”

Simpson displays a stunning empathy at these moments towards the beasts she has no choice but to slay in order to survive. She feels less empathy, however, for those men who greedily slash down the trees, refusing to consider the long-term consequences for any other species but themselves. No, she deduces, they don’t even care about their own long-term survival: muddying creeks, inviting the pine beetle with their monocultures, wrecking sources of oxygen, deleting sustenance of all kinds. I was adrift in admiration at Simpson’s ability to continue to hold faith in the land and to maintain the often-futile tussle against the logging executives who are always found not-guilty of breaking environmental laws. “To leave without a fight would be unthinkable,” she states, “I was raised to take responsibility.” No doubt about that. Not for an instant in this account does Simpson shirk one demand, and within the challenges, she continues to take pleasure in her dogs, her family, nature and that steaming cup of coffee that usually awaits her at the end of tumult or duty.

Alone in the Great Unknown is illustrated randomly with dreamy watercolour sketches Caroll painted (yet another talent!) of the lodge, a blue jay, her dory, and looming bears, along with a few maps pinpointing the location of this region and, although it needed much more stringent editing for stylistic laxness and a lack of consistency, this narrative remains a tale that etches itself in the mind like a drawing and a scar. By the final chapter, when Simpson is in her fifties, she has found love again with a wilderness guide, Helmut, with whom she remains at the lodge until 2018, taking satisfaction in how much of the land her persistence was able to save. Eventually tearing herself away from this quarter-century obsession to live a less arduous life on a sailboat, she concludes with the acknowledgement that “all the pain and the beauty of wilderness-living has filled my heart, which will beat forever in the rhythm of the northern lights.”

*

Catherine Owen was born and raised in Vancouver by an ex-nun and a truck driver. The oldest of five children, she began writing at three and started publishing at eleven, a short story in a Catholic Schools writing contest chapbook. She did her first public poetry readings in her teens and Exile Editions published her poetry collection on Egon Schiele in 1998. Since then, she’s released fifteen collections of poetry and prose, including essays, memoirs, short fiction and children’s books. Her latest books are Riven (poems from ECW 2020) and Locations of Grief (mourning memoirs from 24 writers out from Wolsak & Wynn, 2020). She also runs Marrow Reviews on WordPress, the podcast Ms Lyric’s Poetry Outlaws, the YouTube channel The Reading Queen and the performance series, 94th Street Trobairitz. She’s been on 12 cross-Canada tours, played bass in metal bands, worked in BC Film Props and currently runs an editing business out of her 1905 house in Edmonton where she lives with four cats. Editor’s note: Catherine Owen has also reviewed books by Hilary Peach, John Armstrong, and Jason Schneider for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1733 Maintenance and sustenance”

We were on holiday from the UK in Terrace BC and popped into Misty River books and asked for some recommendations to give us a local flavour for our holiday reading – and this was in the pile. Both my husband & I read it through in almost one sitting – it was quite captivating, and enlightening as it really shed a different light on the logging that we saw as we travelled.

Book sounds fascinating! The author is a neighbour here in Mexico.