1721 Naming British Columbia

An essay by Patrick A. Dunae

Naming British Columbia

*

The British Columbia Review is a year old. Previously known as The Ormsby Review (2016), it was renamed The British Columbia Review on February 10, 2022. The new name was greeted enthusiastically, for the most part.[1] A few readers were unhappy that it had ‘British Columbia’ in the title. They were unhappy because, to them, the name evoked colonialism, Christopher Columbus and the discredited doctrine of discovery.[2]

Recent debates about ‘de-naming’ and ‘re-naming’ British Columbia involve modern connotations of the name and some historical misconceptions.[3]

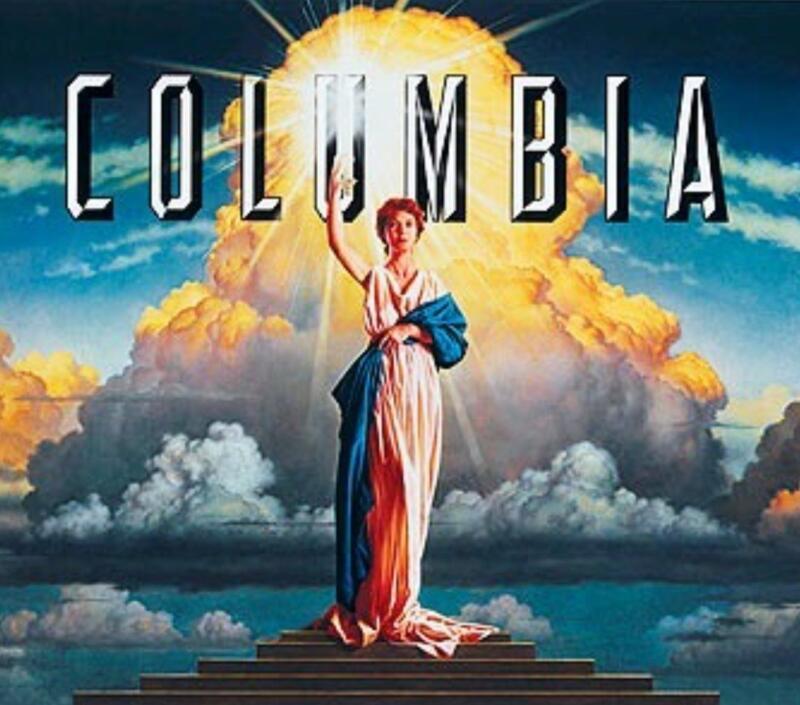

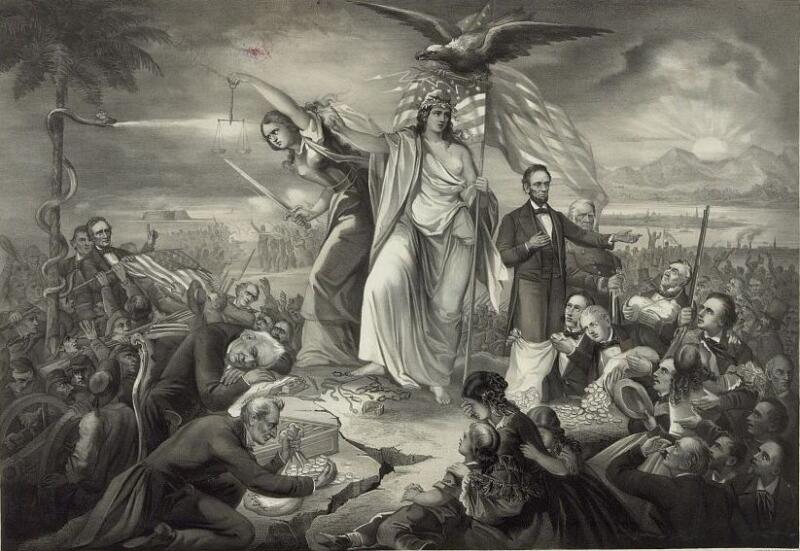

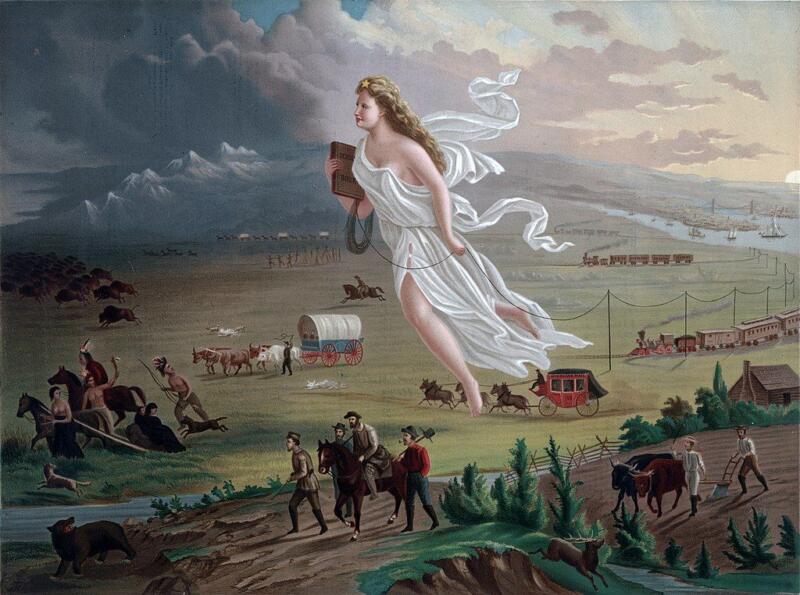

The Knowledge Network documentary series, British Columbia: An Untold History (2021), was not helpful in explaining the derivation of the name.[4] In the episode that touched on the topic [Episode 1, part 2], Coll Thrush, an historian at The University of British Columbia, associates the name ‘British Columbia’ with American ‘manifest destiny’ and westward expansion. The images that illustrate his commentary are drawn from American popular culture. The images include a recruiting poster for the US Army and the logo of Columbia Pictures film production studio.[5]

In fact, British Columbia takes its name from the Columbia Department of the Hudson’s Bay Company, as Richard Somerset Mackie explained in Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997). The Columbia Department was an administrative unit defined by natural terrain and watersheds and by diplomatic treaties and conventions. It was “intersected by major salmon rivers, which drained southward and westward through perpetually mountainous country to the Pacific Ocean…The department extended, officially, from the northern frontier of Mexico at the forty-second parallel to Russian America, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean” (p. 70).

The Columbia Department was named for the largest river in the region, which had been named in 1792 for an American trading vessel, Columbia Rediviva. The region, which was known in the United States as the Oregon Territory, was jointly occupied by Great Britain and the United States, without regard to its Indigenous inhabitants, from 1818 to 1846. It was then divided along the 49th parallel and apportioned between Britain and the USA by the Oregon Treaty (aka Treaty of Washington, 1846). A dozen years later, in 1858, the Fraser River gold rush prompted the British government to forestall US ambitions north of the 49th parallel by creating a new colony called British Columbia.

The name was chosen quickly but not carelessly. The Colonial Secretary, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, initially considered the appellation ‘New Caledonia,’ a name used earlier in the Pacific fur trade for territory in the northern part of the Columbia Department. However, France objected since it had recently (1853) established a colony by that name in the south Pacific. Accordingly, Lytton asked Queen Victoria to recommend a different name. She conferred with her husband, Prince Albert, on the matter.

After studying maps of the region, Albert suggested ‘British Columbia.’ The suggestion was conveyed to the Colonial Secretary in a letter over the Queen’s signature on July 24, 1858:

If the name of New Caledonia is objected to as being already borne by another colony or island claimed by the French, it may be better to give the new colony west of the Rocky Mountains another name. New Hanover, New Cornwall and New Georgia appear from the maps to be names of subdivisions of that country, but do not appear on all maps. The only name which is given to the whole territory in every map the Queen has consulted is ‘Columbia,’ but as there exists also a Columbia in South America, and the citizens of the United States call their country also Columbia, at least in poetry, ‘British Columbia’ might be, in the Queen’s opinion, the best name.

The proposed name was suitable and legislation creating a new colony called British Columbia received Royal Ascent on August 2, 1858.

The story behind Queen Victoria’s choice of the name was not widely known until John T. Walbran’s compendium, British Columbia Coast Names…Their Origin and History, was published in 1909. Captain Walbran’s source was a newly-published collection, Letters of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty’s Correspondence Between the Years 1837 and 1861 (London: John Murray, 1907).[6]

Walbran’s account was confirmed and enlarged by a British historian, Ged Martin, in a scholarly essay with a straightforward title, “The Naming of British Columbia.” The essay was published in 1978 in Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies.[7] It was based on Martin’s research with primary documents in the Royal Archives in Windsor Castle, British Parliamentary records and contemporary newspapers.

As Martin notes, some of Lytton’s political opponents derided the name of the new colony for being dull and unimaginative. Alternative suggestions offered by government critics included “Pacifica” and “the anglicization of some Indian name.”[8] Had the Colonial Secretary accepted one of the alternative suggestions in 1858, the name of our province might not have been as prosaic or as problematic.

As for the name on the masthead of this publication – when the new title was unveiled last year, Richard Mackie, the editor and publisher acknowledged, in a jocular comment to a contributor, that there was an antiquated or anachronistic feel to the name, ‘British Columbia.’ Yet the name was significant to him as a BC historian for being a legacy of the fur trade and an inheritance of the political and commercial entity known as the Columbia Department, which had also, by 1846, seen the ethnogenesis of distinctive mixed-blood communities west of the Rocky Mountains derived from the Iroquois, French Canadian, Kanaka (native Hawaiian) and Metis employees of the North West Company and Hudson’s Bay Company.[9] And from a publisher’s perspective, the title British Columbia Review telegraphs clearly its inclusive intent. “Our new name,” Richard wrote in Issue No. 1367, “confirms and reflects the true scope and breadth of our engagement with British Columbia.”

*

Patrick A. Dunae was born in Victoria and lives there now. He taught BC history at the University of Victoria and Vancouver Island University. Previously, he was an archivist in the Manuscripts and Government Records Division of the British Columbia Provincial Archives. Editor’s note: Patrick Dunae has also reviewed books by Sean Carleton, Linda Eversole, Bethany Lindsay & Andrew Weichel, Jenny Clayton, and Valerie Green, and he has recently reviewed the television docuseries British Columbia: An Untold History for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] “The new British Columbia Review,” The British Columbia Review, formerly The Ormsby Review, 1376 (10 February 2022).

[2] Michael Turner, Websit: https://mtwebsit.blogspot.com/2022/03/iron-goddess-of-mercy-2021.html.

[3] Jennifer Cole, “It is time to rename British Columbia,” Toronto Star (29 June 2021); Andrew Fleming, “Making the case for renaming British Columbia,” iPolitics.ca (4 August 2021); Robert Jago, “Renaming Places: How Canada is re-examining the map,” Canadian Geographic (22 July 2021); Ry Moran, “De-Naming British Columbia,” Canada’s History, 101:4 (August-September 2021).

[4] Knowledge Network. British Columbia: An Untold History. https://www.knowledge.ca/program/british-columbia-untold-history.

[5] The segment with Professor Coll Thrush opens with the image of Columbia, as depicted in the 1992 version of the Columbia Pictures logo and segues to a print by Charles Kimmel, published in 1865, about the American Civil War. Thrush then expounds on an allegorical work created in 1872 for an American publisher by John Gast, a Brooklyn-based painter and lithographer. Entitled “American Progress,” it shows an ethereal female figure in classical garb, usually identified as Columbia, with the star of empire on her forehead and carrying a coil of telegraph wire. She floats over railways, advancing white settlers and retreating bison, bears, and Indigenous people. This segment of the Knowledge Network documentary about British Columbia history concludes with an image of a recruiting poster from the First World War, with the exhortation “Columbia Calls: Enlist Now for the U. S. Army.” The poster, created by Vincent Aderente in 1917, features an image of Columbia bestriding North America, holding a sword and billowing American flag. [British Columbia: An Untold History, Episode 1, part 2, 14:06 – 15:06 minutes].

[6] John T. Walbran, British Columbia Coast Names, 1592-1906…Their Origin and History (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1909), p. 63. Walbran was citing Letters of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty’s Correspondence Between the Years 1837 and 1861, edited by Arthur Christopher Benson and Viscount Esher (London: John Murray, 1907), Volume 3, 1854-1861, chapter XXVII, p. 376.

[7] Ged Martin, “The Naming of British Columbia,” Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Autumn, 1978): 257-263.

[8] Martin, “Naming of British Columbia,” 259.

[9] Richard Somerset Mackie, Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific 1793-1843 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997), p. 322. See Tom Koppel, Kanaka: The Untold Story of Hawaiian Pioneers in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: Whitecap Books, 1995) as well as Jean Barman’s trilogy: French Canadians, Furs, and Indigenous Women in the Making of the Pacific Northwest (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014); Abenaki Daring: The Life and Writings of Noel Annance, 1792-1869 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016); and Iroquois in the West (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019).

2 comments on “1721 Naming British Columbia”

Please tell me where I can obtain a copy of Patrick’s essay.

Really good analysis. I flipped when I saw that “Columbia” bit on Knowledge Network. Thanks for the timely and synchronized essay that corrects the nonsense. Incidentally, the 49th parallel work was done by David Thompson but he didn’t reckon on a little southerly jut on the coast — Point Roberts. Now every day, a school bus chugs down to the Peace Arch border with school children to get their daily dose of American education. It just goes to show you what Gore Vidal said is true: they should rename the US political parties the Land Party (one red, one blue — “The United States of Amnesia” documentary) because that is all they’re interested in. Imagine if Washington State north of the Columbia was in current BC territory? If so, it is highly unlikely that Hanford and the nuclear degradation on the Columbia would ever have taken place. Congrats Richard Mackie and BC Review supporters on keeping this digital publication humming along.