1105 Lives of Victoria sex workers

Victoria Unbuttoned: A Red-Light History of BC’s Capital City

by Linda J. Eversole

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2021

$20.00 / 9781771513388

Reviewed by Patrick A. Dunae

*

For over a century, Victoria, British Columbia has promoted itself as a city of gardens, as a haven for genteel tourists and wealthy retirees. But as Linda Eversole reminds us, there was a seamy side to the city’s social character. Victoria was a seaport and in the late nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century its population included a large number of single men. Prostitution, not surprisingly, was prevalent. Street prostitution was always discouraged, but brothels abounded. In the 1880s, Victoria was the sexual emporium of the Pacific Northwest. The sex trade expanded during the Klondike gold rush: in 1900, Victoria’s police chief estimated that there were nearly 300 ‘known prostitutes’ in the capital city. The sex trade was eventually curtailed by economic factors and a moral reform movement prior to the First World War. But in its heyday, the sex trade in Victoria was flagrant.

For over a century, Victoria, British Columbia has promoted itself as a city of gardens, as a haven for genteel tourists and wealthy retirees. But as Linda Eversole reminds us, there was a seamy side to the city’s social character. Victoria was a seaport and in the late nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century its population included a large number of single men. Prostitution, not surprisingly, was prevalent. Street prostitution was always discouraged, but brothels abounded. In the 1880s, Victoria was the sexual emporium of the Pacific Northwest. The sex trade expanded during the Klondike gold rush: in 1900, Victoria’s police chief estimated that there were nearly 300 ‘known prostitutes’ in the capital city. The sex trade was eventually curtailed by economic factors and a moral reform movement prior to the First World War. But in its heyday, the sex trade in Victoria was flagrant.

In recent years, the historical aspects of prostitution in Victoria have been considered by several writers, including this reviewer, but Linda Eversole is peerless in describing the women who comprised the demi-monde of the city. She brings formidable research skills and an engaging writing style to her narrative. Her abilities were demonstrated in her previous book, Stella: Unrepentant Madam (TouchWood Editions, 2005). It described the tumultuous life of Estella Carroll, a feisty brothel owner in Victoria in the early 1900s. Victoria Unbuttoned: A Red-Light History of BC’s Capital City covers a longer chronological period and involves a larger cast of characters. It is informed by an impressive number of primary and secondary sources. While the book is mainly descriptive, it provides a cogent analysis of contemporary activities, attitudes and societal values.

The author’s research skills were honed during her career as a public historian. She worked as an assistant to Victoria’s first archivist, Ainslie Helmcken, and for many years was a research officer for the BC government’s Heritage Branch. She has also worked at the Provincial Museum and several smaller museums. Her knowledge of archival government records and legal documents – such as transcripts of court proceedings, probate files, chattel mortgages, and inquests – adds authority to her work. Her expertise as a genealogist provides depth and detail to her character sketches. She has used her skills in “forensic genealogy” (p. 6) to track present-day descendants of some of the women featured in this book.

The author provides biographies and vignettes of over a dozen women to discuss the dynamics of the sex trade in Victoria, beginning with the colonial period and concluding with the closing years of the Edwardian era. In the opening chapter, she describes dance houses, where miners consorted with Indigenous women, and music halls that were associated with licentious activities. Here we meet Nettie Sager, an exuberant music hall performer who provided sexual services from the Star & Garter, a saloon on Government Street, in the mid-1860s. She was described in police court as “‘a notoriously bad character.’” “Where Nettie originally came from, and where she ended up, is lost in the historical records, perhaps to be discovered one day” (p. 39).

Most of Victoria’s prostitutes came from the United States. In the 1870s, this sorority included Martha Gillespie, who grew up on a farm in Iowa. Her life began in an unremarkable way but she flouted conventions when she came to BC. Brazenly, she married more than once even though her spouses were living. “Martha went on to become a well-known participant in police court with charges of stealing and the use of loud and obscene language in the streets” (p. 53). She disappeared from Victoria in the mid-1880s and may have engaged in the sex trade in Portland, Oregon. Victoria had close ties to Portland during these years.

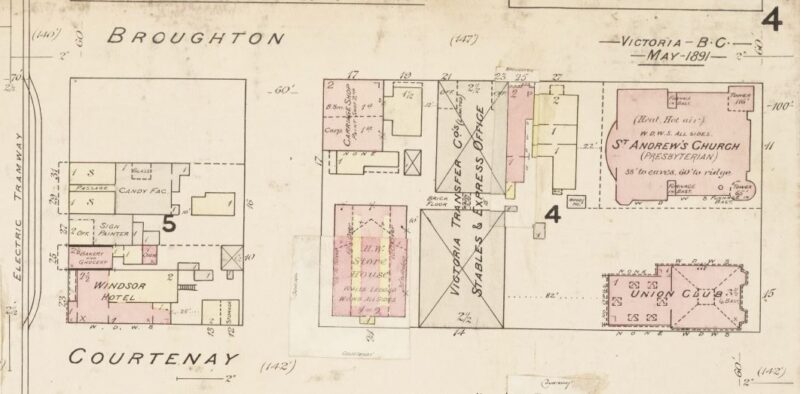

There were also close ties to San Francisco, California, and many madams and brothel prostitutes from the Bay City feature in Victoria Unbuttoned. By way of introduction, the author reproduces a list of ‘houses of ill fame in the City,’ compiled by the chief of police in April 1886. It records the names of over a dozen brothel operators, the street location of their premises, and the names of property owners. The owners include a city alderman, a provincial government cabinet minister, and a recent mayor. The ex-mayor, who was also a former police officer, rented his property on Broughton Street, between Government and Douglas streets, to Fay Williams, a well-known madam from San Francisco. Henrietta Morgan’s name is on the list. Morgan, who came to Victoria from San Francisco, was one of the “owner-operators” in the brothel business (p. 61). A few months after the list was compiled, Morgan died, apparently of natural causes. Her estate was contested and the author has used court records to illuminate aspects of her life. Henrietta Morgan is buried in Ross Bay Cemetery, her resting place marked by “a small, ornately carved gravestone” (p. 64).

The author recalls some of the “lost souls” of the demi-monde – that is, the sex trade workers who were addicted to drugs and alcohol and suffered from depression. Edna Farnsworth was one of these unfortunate women. In June 1889, she died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound in a Broughton Street bordello. She was twenty years old and a sojourner from San Francisco. The tragic event of her suicide and the subsequent inquest were covered extensively in Victoria’s two daily newspapers. The circumstances of her death and burial have been discussed in several historical works. Edna Farnsworth is buried in Ross Bay Cemetery. The headstone on her grave was expensive (p. 79) and is quietly impressive to this day. Questions remain as to who paid for her funeral and grave marker.

The sex trade, as the author points out, was vexatious to churchmen and their respectable congregations in the centre of the city. Brothels on Broughton Street bedevilled St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church; Broad Street brothels were noxious to the Methodist Church on the corner of Pandora Avenue; and ‘disorderly houses’ on View Street were anathema to St. Andrew’s Roman Catholic Cathedral. Pastors, priests and prelates complained about them constantly. Periodically the police would raid them and close them down, briefly. On these occasions, the female occupants would be arrested and charged for being a ‘keeper’ or an ‘inmate’ of a ‘common bawdy house.’ Sometimes, but not often, male customers would be charged with the offence of being a ‘frequenter’ in a bawdy house. The miscreants were brought before a police court magistrate and, if found guilty, they paid a fine of between $10 and $50. The financial penalties were not onerous: for sex trade workers, it was the cost of doing business. Brothel operators and employees might also be sentenced to jail, but the punishment was perfunctory. The author mentions a case in the 1890s when a madam known as Maud Lord was fined $50 and sentenced to just one hour in jail (p. 89).

Civic authorities in Victoria were rather permissive because prostitution was regarded as a ‘necessary evil,’ to protect the dignity of respectable females; and because the sex trade was important to the local economy. During the Klondike gold rush, when the sex trade burgeoned, Victoria merchants asked the local constabulary to go easy on the prostitutes who worked from small, one-room premises known as ‘cribs’ on Chatham Street. The merchants were concerned that men bound for the Yukon would purchase their provisions and mining equipment in Seattle or Vancouver if sexual services were not easily available to them in Victoria.

The landscape of sexual commerce in Victoria changed, physically and politically, around 1910. A conflagration in July 1907 wiped out the cribs on Chatham Street. Fortunately, there were no casualties from the fire but the cribs were never rebuilt. [The parking lot of Capital Iron in Victoria marks the spot where the wood-frame cribs once stood.]

About the same time, a civic reform movement that sought to promote ‘social purity’ swept through American and Canadian cities, including Victoria. Reform-minded councillors endeavoured to restrict the sex trade to the western end of Chatham Street and Herald Street, where brothels were tolerated for a while.

The more fashionable ‘parlour houses,’ which had been operating near the commercial centre of Victoria for many years, were also affected by a chilly moral climate and increased property values. Between 1912 and 1914, several prominent madams sold their houses or terminated their leases and returned to the United States. As the author observes, the sex trade in Victoria was not eradicated, but it became a sub rosa activity that was conducted with discretion (p. 169). It was never as flagrant or flamboyant again.

Victoria Unbuttoned is concerned primarily with heteronormative sex between white men and women, although brothels in Victoria’s Chinatown are described (pp. 43-46) and a controversy involving a rescue home for Chinese girls and women is discussed at some length (pp. 149-157). “A lack of primary material and my own lack of cultural understanding precluded my including more in-depth stories on women from the Indigenous, Chinese, and Japanese communities in Victoria,” the author writes. “I hope in time others will follow – those who can dig deeper and find equally compelling stories to join the ones in this book” (p. 172).

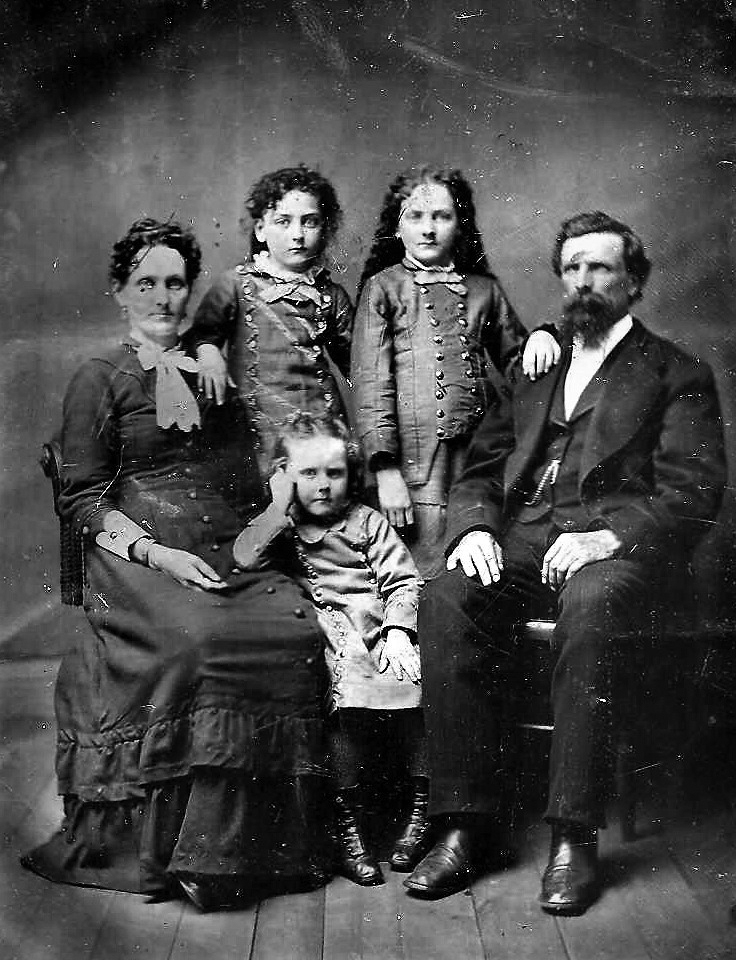

The stories in this book are indeed compelling. The author has extended her research scope from newspaper reports, nominal census records and police charge books (which are still important sources for historians) to family lore and personal keepsakes. In so doing, she demonstrates her skills in forensic genealogy.

Consider, for example, the author’s account of Maud Lord, aforementioned, who ran a brothel on Broughton Street. The woman’s real name was Dora Son and she was born in Ogden, New York. She came to Victoria in 1890 and died there of meningitis in 1898. Her life might have been forgotten but for the author’s assiduous research. Linda Eversole traced the deceased woman to her daughter, who grew up respectably and eventually settled on Orcas Island. When the daughter passed away in 1954 “her family honoured her last wish to be buried with her mother in Victoria’s Ross Bay Cemetery” (p. 94). The family provided the author with striking photographs of Dora Son – aka Maud Lord – that are reproduced in this book.

Forensic genealogy also reveals the life of Lillian Gray, of Tampico, Illinois, who came to Victoria via San Francisco in the early 1900s. After working with Stella Carroll, she opened a brothel in Vancouver’s red-light district. In 1913, after repeated run-ins with the law, Gray went back to California. Years later, she returned to her home state of Illinois where she died in 1948. The author located her descendants and found correspondence and a family portrait. Pictures of Lillian Gray, provided by her descendants, grace the front cover and back cover of this book.

Along with pictures from family members, the book includes images from the City of Victoria Archives and other archival repositories. It’s worth noting that none of the illustrations come from the BC Archives, probably because of the prohibitive cost of reprographic fees charged by that public institution.

The book includes Criminal ID photos, commonly known as ‘mug shots,’ from the Victoria Police Museum and Archives and its counterpart in Vancouver. The mug shots of women who were arrested and charged with prostitution-related offences are intriguing. In many cases, the women are dressed in their finery. They strike flattering poses. Typically, the women in these photos were arrested following a police raid on a brothel. Were they given an opportunity to freshen up before their mug shots were taken at the police station?

Fire insurance plans are valuable sources of information for urban historical studies and the author has used plans from the 1880s and 1890s in her research. Details from a couple of fire insurance plans are reproduced on pp. 48 and 84. Unfortunately, the images are so small that they are almost illegible. The original records are large and sumptuous. The plates in fire insurance atlases are 21” x 25” [53 cm x 63.5 cm], drawn to a scale of 1 inch to 50 feet [2.5 cm to 15 m] and were printed in colour. It would be too expensive to reproduce them adequately in this book, but the bibliography might have included a URL to University of Victoria Libraries where high-resolution images of plans created for the firm of Charles E. Goad are freely available. The documents are posted at: https://vault.library.uvic.ca/collections/6cf241ab-b4ef-44c2-8b6c-38a9de32f7d5

To give credit where it is due, the BC Archives provided copies of fire insurance atlases from its collection to the University of Victoria for digitization.

With regard to the bibliography, when Victoria Unbuttoned goes into a second edition, as surely it will, the author and a copy editor need to tweak the list of Selected Sources. Sub-titles matter. Some of the works cited in the bibliography have both title and sub-title, as is proper. Hence, an informative book by Eve Lazarus is listed as Sensational Victoria: Bright Lights, Red Lights, Murders, Ghosts & Gardens (Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2012). But many of the books cited in the Selected Sources section are identified with their main titles only. Valerie Green’s book, No Ordinary People (Victoria: Beach Holm Publishers, 1992) is shorn of its subtitle: Victoria’s Mayors Since 1862. A very useful book by Glen A. Mofford is listed simply as Aqua Vitae, without its subtitle, A History of the Saloons and Hotel Bars of Victoria, 1851-1917 (Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2016).

One of the first scholarly accounts of Victoria’s sex trade was written by an undergraduate student, C. L. (Lacey) Hansen-Brett. The bibliography in Victoria Unbuttoned refers to an unpublished paper that Hansen-Brett submitted for a course at Camosun College (Victoria) in 1984. The paper was revised and published under the title “Ladies in Scarlet: An Historical Overview of Prostitution in Victoria, British Columbia,1870-1939,” in British Columbia Historical News, Vol. 19, No. 2, 1986: 21-26. The published version of Hansen-Brett’s essay should be cited in the bibliography in the next edition of Victoria Unbuttoned. (Hansen-Brett’s essay is now accessible online via the British Columbia Historical Federation portal and UBC Library Open collections.)

A map showing the locations of brothels and other sites of sexual commerce mentioned in the book would be appreciated by readers who may not be familiar with downtown Victoria. A map could also provide the basis of a walking tour in a fairly compact area, starting from Chatham Street and proceeding south via Broad Street to Broughton Street.

Still, without a map, this is a very good book. The author is to be applauded for researching and writing it and TouchWood Editions for bringing it to the public. Engaging and informative, and affordably priced at just $20, it has the hallmarks of a bestseller.

The book is authoritative, with endnotes, an extensive list of primary and secondary sources, and an index. It is an important addition to the historiography of Victoria, BC.

The author concludes her book on an encouraging note, by inviting others to join in the task of “continued and diligent research” and to share their discoveries (p. 173). In this manner, we might tell the stories of those who were denied a voice in the past. Linda Eversole’s new book, Victoria Unbuttoned, is an excellent starting point for a journey of historical discovery.

*

Patrick Dunae was born in Victoria and lives there now. He taught BC history at the University of Victoria and Vancouver Island University. Editor’s note: Patrick Dunae has also reviewed books by Bethany Lindsay & Andrew Weichel, Jenny Clayton, and Valerie Green for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1105 Lives of Victoria sex workers”

Patrick, I enjoyed this excellent, thoughtful review. Well done!