1703 The Holocaust past and present

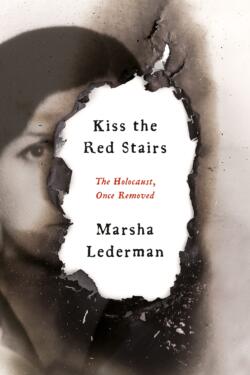

Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed

by Marsha Lederman

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (McClelland & Stewart), 2022

$35.00 / 9780771049378

Reviewed by Charlotte Schallié

*

“Kiss the Red Stairs. The Holocaust, Once Removed” is a deeply resonant memoir exploring the interconnectedness of history, memory and lived experience in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Marsha Lederman, who is the Western Arts Correspondent for The Globe and Mail, is a skilled storyteller and investigative journalist; it is in this dual role that she bridges a memoirist’s need for introspection with the study of history and her own pursuits aimed at unearthing the remnants of her family’s missing past. As the daughter of Holocaust survivors, Lederman faces an inherent conundrum. The Holocaust has been both all-consuming and elusive for much of her adult life. While the history of her parents’ survival is intertwined in her present-day life, it is also filled with blind spots, silenced voices and unknown knowledge. She writes, “[t]he past that I haven’t lived, but that I think lives in me” (p. xv). Children of Holocaust survivors know this all too well. It is unbearable to one’s own soul and conscience “to ask the right questions and find out what exactly happened to your parents, from your parents” (p. 17) if it will reignite the pain and memory of sustained degradation and dehumanization. It is thus not until the breakdown of her marriage and the onset of an intense and prolonged period of grief that the author begins pondering how the absorption of “these stories through some sort of domestic osmosis” (p. 14) impacted her identity, wellbeing and resilience as the child of Holocaust survivors.

“Kiss the Red Stairs. The Holocaust, Once Removed” is a deeply resonant memoir exploring the interconnectedness of history, memory and lived experience in the aftermath of the Holocaust. Marsha Lederman, who is the Western Arts Correspondent for The Globe and Mail, is a skilled storyteller and investigative journalist; it is in this dual role that she bridges a memoirist’s need for introspection with the study of history and her own pursuits aimed at unearthing the remnants of her family’s missing past. As the daughter of Holocaust survivors, Lederman faces an inherent conundrum. The Holocaust has been both all-consuming and elusive for much of her adult life. While the history of her parents’ survival is intertwined in her present-day life, it is also filled with blind spots, silenced voices and unknown knowledge. She writes, “[t]he past that I haven’t lived, but that I think lives in me” (p. xv). Children of Holocaust survivors know this all too well. It is unbearable to one’s own soul and conscience “to ask the right questions and find out what exactly happened to your parents, from your parents” (p. 17) if it will reignite the pain and memory of sustained degradation and dehumanization. It is thus not until the breakdown of her marriage and the onset of an intense and prolonged period of grief that the author begins pondering how the absorption of “these stories through some sort of domestic osmosis” (p. 14) impacted her identity, wellbeing and resilience as the child of Holocaust survivors.

The headings of the three parts comprising the memoir (Generations, Trauma, Home) gesture toward an entanglement of seemingly separate strands of narrative. Lederman compellingly shows that past and present experiences are interconnected including moments of sorrow, solace and joy. The ripple effects of mass atrocities are profound; they cannot be erased through geographical separation or temporal distance. As Lederman retraces her parents’ lives and the circumstances of their survival in German-occupied Poland and Germany (Part One: Generations), she collects and reassembles fragments of recorded history and living memory. We learn about Jacob Meier Lederman — Marsha Lederman’s father — his survival in the Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto, his escape, and his use of falsified documents purporting to be Polish Catholic. Jacob became Tadeusz (Tadek), made his way to Germany and survived on a farm in Holsen, North Rhine-Westphalia. While much of Tadek’s story can be recovered, critical details remain unknown. For Lederman, the retelling of her father’s biography is thus tinged with sadness and regret; she repeatedly blames herself for not having asked more questions during his lifetime. For not having been closer to him. Similarly, as the author uncovers more details about her late mother’s harrowing experience as a slave labourer at a munitions factory near the Radom Ghetto, in Auschwitz and Lippstadt, she questions her own reluctance to explore these stories together with Gitla Lederman while there was still time to do so in the past, “during the many years I had with my mother” (p. 50). Lederman recollects that when she was finally prepared to sit down with her mother for an in-depth one-on-one interview in Florida, it was too late. Gitla Lederman had died of a heart attack a few days prior to her daughter arriving in North Miami.

Marsha Lederman’s gift as a storyteller is to create a cohesive patchwork of interlocking narratives. Oftentimes, in the absence of first-hand accounts, she approaches the stories of her parents through stories of them being told by others. A common thread are chance encounters, serendipitous discoveries, unexpected parallels and missed opportunities. For example, she retraces how her displaced parents incidentally met one another in Kaunitz, fell in love and started a life together in the country of their former perpetrators. Her parents’ love for one another is one of many “little miracles”, as she describes them. These are random moments of beauty and new beginnings in the aftermath of unimaginable loss and devastation.

Another thread, both consistent and haunting, is the author’s inability to connect with the emotional truth of her parents’ lived experiences. “Their history was like an ominous shadow that hung just beyond reach, and well beyond comprehension” (p. 91). Lederman amasses copious amounts of research literature, connects with experts in the field, and conducts her own primary source research. Yet, it never seems to be enough. There is always a new inquiry, a new relentless quest fuelling her obsession with the Holocaust. Can she find the battalion that liberated her mother on April 1, 1945, in Kaunitz? There are questions abound: What was it like for her father to be sheltered in a German farmhouse? Did his protectors know that he was Jewish? For Lederman, these are not just relevant fact-gathering questions to recreate lost family histories, but also urgent interrogations in order to tackle her own “issues” (p. 92). Repeatedly and throughout her memoir, she brings up the possibility that these issues – she recognizes them with emotional honesty and unflinching self-awareness — are somewhat related to her parents being Holocaust survivors. It is this deep and unsettling intergenerational connection that sets in motion her own pursuit to study the role and impact of epigenetics trying to understand the ripple effects of trauma for the second generation. “Always, always expecting the worst. The glass wasn’t just half-empty; it was half-full of poison. Or Zyklon B” (p. 93), Lederman writes deadpan. She frequently uses her signature-style dark humour when it becomes too unbearable to bear witness to the residual effects of the Holocaust in her own life.

As she grapples with the idea of trauma leaving a biological imprint on the second generation (Lederman is not convinced that the theory of epigenetics is conclusive), she documents the various manifestations of “triggering Holocaust associations” (p. 97) in Part Two: Trauma. Lederman takes stock of her life, but she also engages rigorously with the seminal research in this field citing works by Helen Epstein, Natan Kellermann, Rachel Yehuda and Zahava Solomon. However, it is a personal encounter with Indigenous artist, master carver and filmmaker Carey Newman, whose traditional name is Hayalthkin’geme, that affects Lederman most profoundly. “Carey and I were both suffering in a next-generation way at a time when I didn’t have the language to understand it” (p. 192). Learning from and with Carey Newman and his family — Carey Newman’s father is a residential school survivor — Lederman envisions the possibility of creating stronger bonds between Indigenous and Jewish communities while she also acknowledges her own responsibility to create space for pathways toward reconciliation here in Canada.

Ultimately, it is the power of community care that shape Lederman’s post-separation identity allowing her to appreciate a newly found communal sense of being in the world (Part Three: Home). The heartbreaking experience of rupture, both in her marriage, and in her family’s history are countered by many interpersonal acts of kindness. After Lederman’s travel plans to Europe are thwarted by the outbreak of the pandemic, she postpones her visit to her father’s childhood home in Poland (the site of the “red stairs”) and the place in Germany where her mother had been liberated and fell in love with Tadek. It is only now that the significance of the author’s home in East Vancouver (the place she cannot leave due to the pandemic) takes on centre stage. In this final section of the memoir, Lederman confronts her own emotional vulnerability, which (she might not agree with this assessment) is her great strength and source of resilience. As she is able to accept the community support and care during times of intense sorrow, she can gradually allow herself to move toward a place of healing and recovery. Reflecting on the larger implications of kinship and solidarity, Lederman suggests that interpersonal connections across communities are also at the heart of collective forms of witnessing and healing in the wake of genocide and mass violence: “We are all witnesses” (p. 351). As such, both personal and communal expressions of grief, hope and resilience have the potential to transcend boundaries and become deeply intertwined. It is thus fitting that “Kiss the Red Stairs” concludes with the author, her son and his father standing on the bimah at the occasion of her son’s Bar Mitzvah, reading Torah in community. Honouring those who are no longer alive and surrounded by those who are loved and cherished in the present, Lederman writes: “I felt whole. And I felt joy, pure joy. Something that has become part of my life, once again” (p. 362).

*

Charlotte Schallié is a Professor of Germanic Studies and Chair of the Department of Germanic and Slavic Studies at the University of Victoria. Her teaching and research interests include memory studies, visual culture studies & graphic narratives, teaching and learning about the Holocaust, genocide and human rights education, community-engaged participatory research and arts-based action research. She is the editor of But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust (New Jewish Press [University of Toronto Press], 2022).

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster