1684 Gore-Tex and infidelity

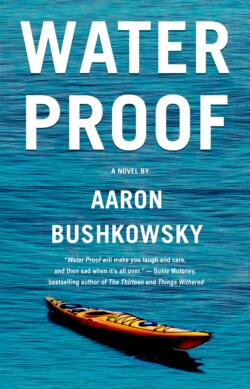

Water Proof

by Aaron Bushkowsky

Toronto: Cormorant Books, 2021

$24.95 / 9781770866362

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

When Shakespeare created a pair of hapless sidekicks called Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, he little knew how similar pairs would proliferate through the following centuries. Samuel Beckett’s Gogo and Didi, like Hollywood’s Laurel and Hardy are amongst the best known bumbling sidekicks, mutually dependent and capable both of minor cruelties and muffled humanity. In his novel Water Proof, Vancouver playwright, poet, and novelist Aaron Bushkowsky cheerfully contributes to the tradition, creating Andy and Will, irascible buddies who spend the novel lurching from one misadventure to the next.

When Shakespeare created a pair of hapless sidekicks called Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, he little knew how similar pairs would proliferate through the following centuries. Samuel Beckett’s Gogo and Didi, like Hollywood’s Laurel and Hardy are amongst the best known bumbling sidekicks, mutually dependent and capable both of minor cruelties and muffled humanity. In his novel Water Proof, Vancouver playwright, poet, and novelist Aaron Bushkowsky cheerfully contributes to the tradition, creating Andy and Will, irascible buddies who spend the novel lurching from one misadventure to the next.

This is not the only easily recognizable tradition that Bushkowsky taps into, however. In a contemporary milieu such as ours, where dark humour seems only too appropriate, the author makes no bones about creating a story that both humorous and dark — very dark. Andy, responsible for almost all the humour, tells us, “Some things aren’t funny. Wolf packs, for example: not funny.” The irony, of course, is that the very way Andy makes the claim is hilarious. And that, in a nutshell, is more or less how this novel works.

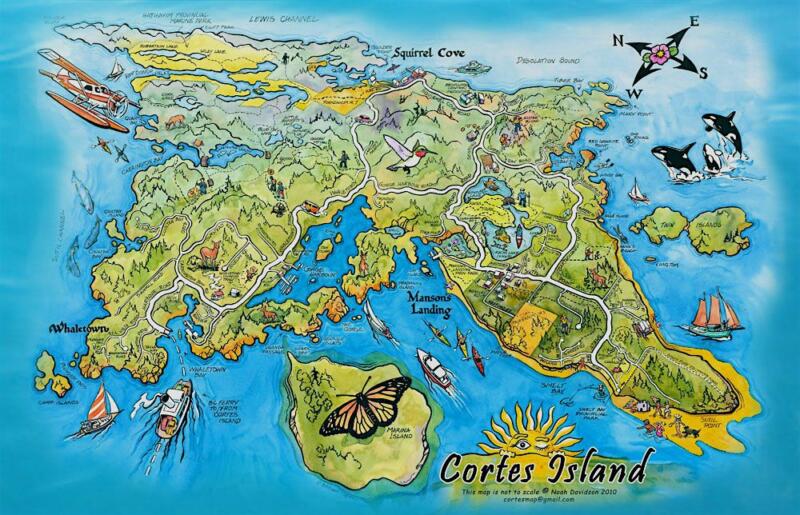

Consider the other “wolves”: the novel begins with a disappearance and apparent drowning. In quick succession it mires the reader in a bog of infidelity and the nearly fatal injury of a young girl. Added to the mix is manipulative drugging, mean-spirited blackmail, incipient bankruptcy, a hostile takeover, unhinged public accusations, deranged suicide attempts, and more. Even the natural world, besides dishing up a threatening wolf pack, complements that with a devastating windstorm, icy, penetrating fog — and, as a bookend to the wolves, a stalking orca. It is not incidental — as Andy darkly points out — that the novel takes place on the shores of a piece of geography called Desolation Sound.

Yet Desolation Sound can be beautiful. This also Andy points out. He also points out much that isn’t dark, but that is almost the opposite of dark. Almost.

In fact, it is one of the traditions of another traditional form, pure comedy, that, whatever the twists and turns of human folly, in the end, some kind of harmony emerges, and, most important, couples unite — or reunite. It would be a bit of a stretch to say that this is, amongst other things, a comedy about love. It would not, however, be a stretch to say that Bushkowsky counterbalances much of the grim and grisly with something altogether more mellow about the possibility of mutual affection and bonding. Of sorts.

How readers experience the grim and grisly and, simultaneously, the merry dance of folly and affection is the result of clearly calculated narrative strategies. As a fundamental strategy, the author breaks his story into a relatively small number of long, almost cinematic, “scenes”, stuffed to the gills with dialogue and descriptive action. Further, he chooses to play with the chronology in such a way that he maintains a kind of suspense, while entangling the action in thorny revelations from the past.

The opening scene, the fulcrum of the whole narration, begins, theatrically, with a moment of crisis during a commercial kayaking trip off Cortes Island, by Desolation Sound. Sarah, one of the kayakers, disappears inexplicably. Sarah, as Bushkowsky soon reveals, is the former secret lover of Andy, our narrator, and, to boot, best friend of Andy’s wife, Anna. In the subsequent search, Andy discovers Sarah’s camera and furtively removes the memory card, the very card, it is soon revealed, that records in awful detail his sexual romp with Sarah.

The plot takes a twist: a local woman, called Holly, has spied Andy’s quick handedness and, in keeping with her identity as a kind of Cortesian holistic witch, takes to her lair, drugs (and seduces) him, and, hey presto, snaffles the memory card. Might there be blackmail in the offing?

Jump to a scene, months before, in a sweaty Vancouver: Andy is busily shooting a commercial for a self-driving car — until everything goes horribly awry. A child actor is nearly killed. A lawsuit impends. Might Andy lose all his savings? He decides to rope in his sidekick Will, and make the feature film he has always wanted to make — but not, of course, if, he is blackmailed for all he is worth.

Scenes from the past that reveal what had gone nastily wrong in his affair with Sarah play off against later scenes as he and sidekick Will head off to Cortes with the double purpose of working on his film and, by means of a preposterous scheme, of recovering the digital equivalent of an incriminating sex tape.

This forward-driving plot is further darkened and entangled by such scenes from the past as one early in the fateful kayak trip, when Sarah has a suicidal breakdown.

The rest of the novel can best be described as … unpredictable. In fact, most readers by now will have twigged onto the fact that, whatever narrative traditions it may milk, it is as far away from formulaic as Bushkowsky’s soggy Cortes Island is from his heat-baked Vancouver.

While many readers will find these — and many more — narrative complications enough to keep them engaged, there is a good argument to be made that the major impact of the novel is not the action-packed-oddball story, but the voice through which the story is told.

Andy, after all, is a scriptwriter. It is his words and his sensibility that colour every word. Andy loves words, especially words that he both takes seriously and really, really doesn’t. Many writers are told that they need to develop a voice. Andy has a voice in spades.

First, comes the very sound of words and the way their sounds intersect. Compressed puns like “we lumber through the lumber” or “I think I need better internal thoughts, I think” demonstrate the point. Although Bushkowsky rather than Andy has to take responsibility for the book’s title, all too clearly it jauntily tilts against counter-meanings — and all the more wickedly because Gore-Tex, of all things, becomes the book’s central motif. While the rest of Canada may be padded to the nines in down, coastal British Columbians put their stakes on … Gore-tex, expensive, yes, but … waterproof.

In many other ways, words thrive in the novel: some of the most resonant passages serve as a reminder that Bushkowsky is also a poet: “The wind parts her bangs. She grimaces or smiles or does both and lets the fog into her open mouth, swallowing the air with her eyes closed. The camera around her neck knocks at her heart over and over again.”

This unusually lyric passage is more often counterbalanced by more ironic ones, though equally cadenced: Andy’s kayaking group, he observes, is “a small Gore-Tex murder of colour along the pale grey of the rocks. Some stand with paddles still in hand; others sit like they’re roman gladiators on individual stone seats to watch us send somebody to their death.” With passages like this over which to lick their lips, some readers might not care particularly about the main story line.

Many a poet works, as here, through analogy. Bushkowsky mainlines analogy like few others. In some passages, it is all too easy to be dazzled and delighted by the almost overwhelming sequence of wildly inventive similes: “He talks like a deposed general.” “She sips her tea like a queen taking a break from beheadings.” “We rip pieces [of our pretzel] like it’s a twisted, stupid heart and shove them into our mouths like we’re unemployed werewolves.” In many passages, the similes almost replace the narrative altogether: “Sarah slugs back more valerian like she’s a deep-sea mariner on a bender in Calcutta…. She throws back her head as if loosening the grip of a hidden octopus.”

Other passages pull in almost the opposite direction. Suggestive of free verse, sentences of almost staccato brevity manage simultaneously to create a fluid cadence. It may, at this point, however, hardly need pointing out that the most distinctive watermark of Andy’s voice is irony. “Could you for once in your goddamned life not be so cynical?” growls Anna at one point. And for good reason. Slightly earlier he has said, “I always try to make things funny. It’s a thing I do.” Note, however, what he says next: “I’ve been doing it regularly since my father stopped hitting me at thirteen.” It is important to hold onto that detail because, to hear Andy’s voice fully, readers need also to hear that shard of pain.

When, at another point, he claims he has turned into Jack Nicholson to the extent that “just like him … I love golf and sarcasm,” his use of deflation is telling. As much as he uses irony, he uses this kind of deflation for his chief target — himself: ““Deep inside…I know what kind of flawed human I am. Well, mostly on weekends on Friday nights after work. And vodka is involved. And rum. And then Riesling.” Out-Hamleting Hamlet in self-loathing, he repeatedly scratches at the open wound of his own guilt and all round despicability.

The same major principle, but in a minor key, is Andy’s disinclination to strike manly poses, particularly against a backdrop of forest and ocean: “My feet feel like they just went to the dentist, completely numb. I stumble getting to the shore and look amateurish because I drop my sunglasses a couple of times. I want to throw up. I might be seasick. My fingers are white raisins.” It is one of the pleasures of spending time with Andy that he’s good at making fun of himself.

Further to Andy’s credit, it is hardly as if Bushkowsky makes a contrast between a deeply flawed Andy and admirable characters around him. Once readers have experienced each one of the women with whom Andy has had some sort of intimate past — not just Anna, his wife, and Sarah, her friend, but also Gil, an actress and, more alarmingly, Holly — they may feel reluctant to judge Andy harshly.

And, as if to make Andy additionally sympathetic, the author prompts his creation to recall, briefly, but repeatedly, the mean-spirited judgmentalism of his religiose father. Perhaps the grimmest of these is Andy’s reliving a particularly dark moment:

I hear my father’s slippers now sliding across linoleum.

It’s Christmas Eve, and I’ve just knocked over the tree.

He’s coming for me. He’s mad as hell.

Yet Andy doesn’t (detectably) feel sorry for himself. Bushkowsky is clearly nudging his readers to make allowances for his heavy-drinking and deeply flawed narrator.

Arguably most important, though, in turning the tide of readers’ exasperation with their narrator is the fact that clearly he is capable of depths — depths of understanding, depths of appreciation, even depths of thought. This comes in two forms, one negative, one positive. On the negative side is the fact that Andy sizzles with contempt in the face of phoniness and abuse.

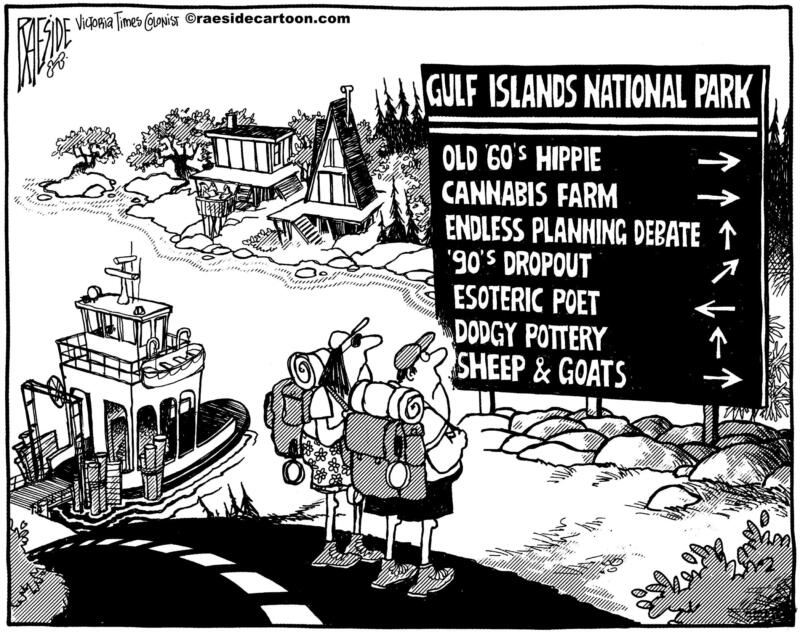

He (with the author pushing him along) can’t help but make wonderfully wry observations on fads of social conformity. As almost a caricature of the all too recognizable Gulf Islands Type, Holly “wears a long, grey dress that looks vaguely Amish with big boots underneath, like workman boots … she stomps from rock to rock like a really pissed Morissette at a stadium concert after a breakup.” His wry take on other equally recognizable Gulf Island stereotypes is just as funny (if a little unfair). As he sees them, they “are a nasty bunch of adamant environmentalists, retired people and yoga instructors wearing Gore-Tex hand-me-downs and man buns.” Norm, leader of a meditation retreat, simply cannot be summed up: he needs to be encountered full strength.

And, lest Andy seem a condescending city slicker trash-talking rural folk, Bushkowsky also makes clear that his withering contempt is equally enthusiastic for city manners, and, especially, hipsters and “foodies”: “We…watch the hipsters walk by pulling on their beards and taking selfies,” he says at one point, and at another, “It’s the kind of bar where chefs go to do shooters after their long, horrible shifts frying halibut to perfection with a Chardonnay reduction cream sauce and capers.”

On an entirely different plane, and far more principled, are Andy’s outbursts against environmental abuses. Walking along the shore at one point, for example, he mutters, “Coke bottles, lids from yoghurt containers, coffee cups. That shit is everywhere….What is it with people? Why can’t we be more responsible? Where is our fucking humanity?”

More important, though, is, not the values he deplores, but those he embraces. When, for example, he says of his surroundings, “Its beauty is almost impossible to capture.…It’s so perfect,” he allows sincerity to ooze through a crack in his habitual irony. And when, later in the same conversation, he adds, ”sometimes I think we’re all on a ferry and we’re all lost souls,” he takes his perception further, even beyond his own ego. In some ways the most highly charged such moment in the novel arises in the form of an encounter, on the small ferry to Cortes Island, with a huge pod of dolphins. His claim of the whole boatload of stunned fellow passengers that “we are all changed” taps into, in fact, one of the most important principles of the book — transformation.

In its most direct and explicit way, transformation is the purported theme of the feature film Andy and Will plan to make. The two-timing protagonists are, in the course of the narrative, to transform. What is framed at one point as “two assholes looking for redemption” at another becomes, disarmingly, “These dudes need to find their hearts.”

And yet Bushkowsky has made not Andy, but his sidekick Will the more extravagant vehicle of transformation. After a numbingly fast romance with the local RCMP woman, Will not only chooses to abandon the film project, but also to change the whole direction of his life and become an environmental activist. Like Andy, he is capable of deflating his own declaimed apotheosis: “Fuck me, he says…. That was embarrassing. Wasn’t it?” Still, he is determined to dedicate the rest of the life to alleviate humanity’s “plundering the planet.”

It is thus through Will’s transformation that the sinister oil tankers that have been ploughing purposefully through the adjacent waters during the whole mad adventure blaze into thematic significance, carrying in their tanks not just oil but also the whole environmentalist weight of the novel. Even the preposterous new director of the proposed movie claims to hope that making the film at Cortes will bring “enough publicity to stop the oil tankers from coming through.”

The oil tankers serve Bushkowsky’s purpose well. Most readers will feel it to be very much beside the point that oil tankers don’t, in fact, at present go through the Strait of Georgia (just as they will feel it to be very much beside the point that Bushkowsky uses a more than free hand with the geography of Desolation Sound and the actualities of kayak touring in the area, not to mention the behaviour of orcas and wolves).

Yet what probably matters even more is the fact that the book ends with a quiet, reflective passage, again presented as something akin to free verse. The final words, “we drift into the unknown” shows how much Bushkowsky wishes to leave his readers neither with a pat resolution to all of the events of the novel, nor with a neatly contained vision of the whole world he has created. In fact, it is only the last words of the Acknowledgements immediately after that allow the end of the novel to drift quietly beyond the storyline, and even its characters.

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at the University of Victoria. Editor’s note: Theo has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has recently reviewed books by Devon Field, Pirjo Raits, Vince Ditrich, Madeline Sonik, Alex Rose, and Frances Peck for The British Columbia Review. Theo Dombrowski lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1684 Gore-Tex and infidelity”