1523 Along the empty corridor of British Columbia

MEMOIR: Along the empty corridor of British Columbia

by Richard Mackie

*

In January 1989, while researching in Winnipeg as part of my doctoral dissertation in Canadian history and historical geography, I had a vivid and unusual dream. My hosts, John and Katherine Selwood, had turned the sunroom at the back of their house in Wolseley into a guest room and, though comfortable, I was acutely aware of the frigid temperature just outside the curtains and the thin pane of glass beside my bed. The rubber tires of cars and buses squeaked over the frozen snow and ice. I shivered in bus shelters on my way downtown to the Hudson’s By Company Archives.[1]

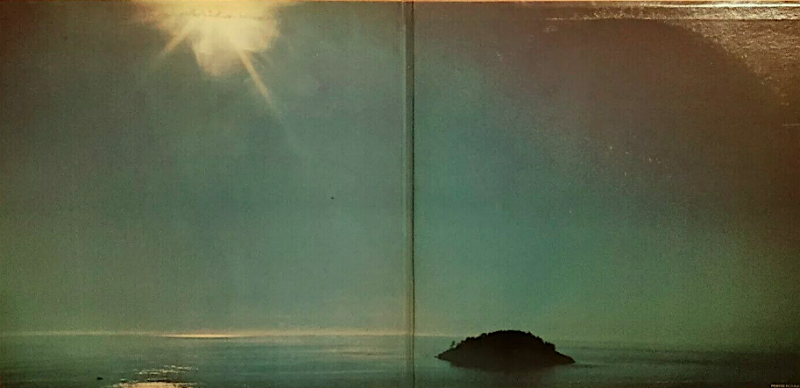

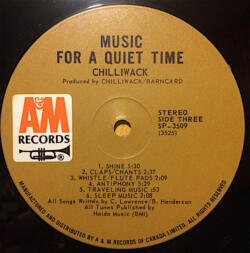

I dreamed that I was standing on the west coast of Vancouver Island looking out to the Pacific Ocean. It was a dazzling postcard view: the setting sun was still bright but sinking, and the near side of small islands turned dark in the shade. I recognized the view: it resembled the inside panoramic photo of Chilliwack’s double album, Chilliwack (1971), one of the first records I ever bought, when I was 14. I used to gaze at this evocative image while listening to my favourite Side 3, “Music For A Quiet Time.”

What was startling was that this view was captioned like a scene from a foreign movie. The caption read, in bold letters, ALONG THE EMPTY CORRIDOR OF BRITISH COLUMBIA. But there was nothing empty in this view of an abundant and verdant maritime coastline. Puzzled, I woke up, wrote the words down, and went back to sleep.

Words, let alone sentences, don’t often appear in my dreams. I assumed that the west coast vision, all greens and blues, was a compensation for Winnipeg’s bone-chilling midwinter, a reassuring reminder of the temperate west coast thousands of miles away. The contrast also seemed connected to my dissertation. I was developing an argument that the fur traders of the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies broke free of the inhospitable and hidebound regions of the continental interior when they reached the lower Columbia River, and then took advantage of an accessible, mild, and resource-rich North Pacific to trade with wealthy and established Indigenous economies, and then initiate ocean-going commerce with diverse commodities including salmon, lumber, coal, and wheat. One of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) men, Duncan Finlayson, wrote, “By its overpowering abundance all nature here demands attention” when he reached Fort Vancouver in 1831.[2]

But if anywhere was empty of accessible resources, especially in winter, surely it was Winnipeg, where nothing was green at that time of year. The BC coastline was always alive, even in winter. So why did the dream combine a quiet and serene vision with a menacing and apocalyptic caption?

While still in Winnipeg the penny dropped. The previous spring, 1988, when I was 30, I had worked as a tour guide on a ship called Clavella on what was then known as the central coast of BC; the “Great Bear Rainforest” would not be coined (by environmentalists Peter and Ian McAllister) until 2006.

The events of this tour, I decided, explained the jarring caption. On the central coast I’d found desolation everywhere: a landscape recently stripped of its natural abundance and emptied of its recent human history. Ghost towns remained where thousands had lived and worked. The logging, pulp and paper, and fishing companies involved had left crumbs and edges behind for the gyppo loggers, small-time operators, and depleted and disinherited Native communities. The central coast had been plundered and the signs of physical trauma were on the land everywhere.

The captioned dream seemed to demand a published article, and as soon as I got back to Pender Island in June 1988 I wrote to a BC publisher, who replied, “Your article could be interesting. On the other hand it could be a cheap shot. Cant about the noble savage vs. the rapacious white I find too boring to read, let alone publish.” Not a promising start! Discouraged, I put the idea aside. I seemed to be barking up the wrong tree, but the publisher wrote back in January 1989:

Last June you wrote me about a possible article on the dubious nature of the whiteman’s [sic] achievement on the central coast. While cautioning that the approach could be spoiled by making it too black and white, I said we would be happy to look at it. Perhaps I should have been more encouraging. The question does in fact interest me very much – it’s THE question in fact. I still hope to read your views on it.

Soon I had a draft ready and sent it to this publisher. He was not impressed. It proved all his worst fears. We had an exchange of letters by Canada Post. He thought my account was unbalanced and that I had insulted the working settlers of the central coast. I replied that I’d presented the trip as I’d experienced it. He wanted me to make a silk purse from the sow’s ears I’d been handed, but I couldn’t invent stories about the “settler achievement” when I hadn’t heard or seen any. Maybe 4 or 5 days on the central coast was not long enough, but what I experienced in that time was a tour of ransacked and depleted resources and abandoned company towns and work camps, their discarded remains rusting and crumbling, their histories consigned to nescience and lost to past inhabitants and future historians alike, and surrounded by resilient Indigenous communities and economies on their postage-stamp-size reserves. That was the reality of what I saw. The publisher’s verdict went against the evidence.

So I kept at it. Over the next two or three years I submitted the essay in turn to Beautiful British Columbia, Canadian Geographic, Canadian Forum, Equinox: The Magazine of Canadian Discovery, This Magazine, and Raincoast Chronicles. I was aware that the content might not match their upbeat visions, but no one wanted it from anywhere on the political spectrum. Nothing else I’d written had met with such a chorus of refusal. Maybe it was nutty to base an essay on a dream? Maybe travel writing was just not my métier? I had articles published in the early 1990s in Beautiful BC, BC Studies, BC Historical Review, The Beaver, and elsewhere, but no one was interested in “The empty corridor.” Maybe it was jinxed. Maybe it needed more work. Maybe it was idealistic, preachy, privileged, pretentious.

After these rejections I showed it to a few friends. A member of my PhD committee at UBC found it “too polemical” and “too harsh on the settler achievement.” I protested that the essay was an accurate account of what I’d seen: I’d encountered a representative sample of human settlements on BC’s central coast and tried to report accurately and fairly on them. Finally, puzzled at the response, I shelved the essay.

I publish it here with some hesitation as a memoir. I hesitate because earlier drafts were turned down many years ago by leading provincial and national publications. The lengthy and pointed comments of the initial publisher still smart when I read them. I would not write the same essay now, 33 years later. But maybe the sentiments expressed were somehow legitimate and even prescient? Maybe the essay and the tour itself were somehow ahead of their time? Maybe its tone and content will now seem more palatable — or even innocuous? It has become almost an orthodoxy to contrast ancient and resilient Indigenous cultures with colonizing, dispossessing, transitory, and despoiling settler societies existing on and drawing wealth from unceded Indigenous land. This essay might even seem polite and tame compared, for example, to the analytical substance of Ian and Karen McAllister’s The Great Bear Rainforest (1997) or Cole Harris’s Making Native Space: Colonialism, Resistance, and Reserves in British Columbia (2003). The coast I visited in 1988 had indeed been emptied of its wealth in salmon and timber — a topic I would later explore in detail [3] — but since that time, concepts of conservation, sustainability, and eco-tourism have taken hold. – Richard Mackie, July 11, 2022

*

In May 1987 Jo Ledingham of the UBC Centre for Continuing Education asked me to be a tour guide the following spring on an expedition tentatively called “Coastal Villages of the Pacific Northwest,” a title I objected to right away for its lumping of BC into what is primarily an American subregion. BC seemed, and seems even more now, quite large and varied enough all on its own without grafting it onto someone else’s bailiwick.

Jo and I were kept busy in the months before the trip, which was soon booked for the week of May 31 to June 6, 1988. We hired a yacht (the 57-foot Clavella, out of Nanaimo) and planned a route from Port Hardy to Bella Bella via Rivers Inlet, Bella Coola, and Ocean Falls. We had no trouble finding seven adventuresome guests willing to forego their annual jaunts to Hawaii or Europe in favour of a local holiday. Every bunk on the ship was occupied. I was one of two tour guides; the other was David Hill-Turner, an industrial historian.

As a student of British Columbia history and archaeology, I was keen to visit the central coast, anxious to visit places that had always exerted romantic and historical fascination. I also hoped to see what remained of the great primary industries of the west coast: logging, pulp and paper, and salmon canning. I did my homework by phoning Gunnar Tosten, BC Packers’ manager at Namu; Jennifer Carpenter at the Heiltsuk Cultural Education Centre at Bella Coola; and a range of experts including SFU archaeologist Philip Hobler and information centres at Port Hardy and Bella Coola. Jo Ledingham also had contacts in Indigenous communities and in coastal tourism and transport. I talked to my archaeologist brothers Alexander Mackie and Quentin Mackie. Quentin had been part of a coastal rock art survey on the central coast a few summers before and was especially helpful and generous.[4]

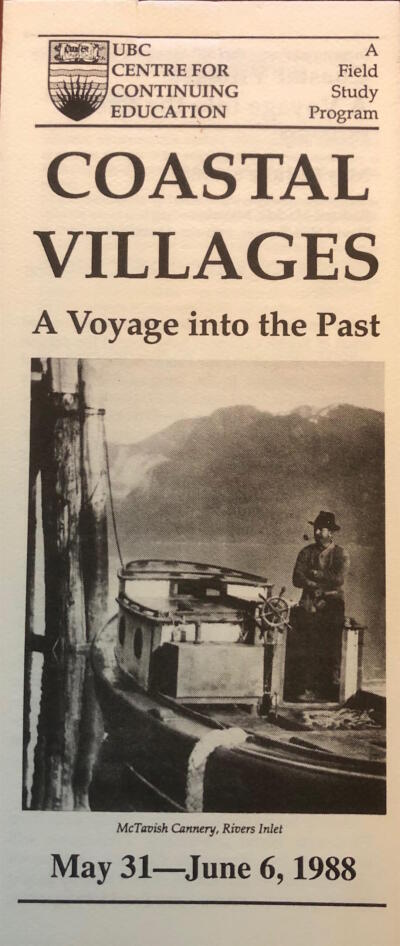

We gave the tour the name “Coastal Villages: A Voyage into the Past.” There was no need to muddy the analytical waters by situating the central coast of BC in the Pacific Northwest. We wanted to emphasize the Native and Euro-Canadian settlements along the way. We designed and circulated a pamphlet bearing a BC Archives photograph of pipe-smoking H. Holland posed in his gas boat Jewel at the McTavish Cannery on Rivers Inlet, as if meditating on the cannery pilings and towering mountains around him.

At this stage I felt a sense of excitement. I was also nervous; this would be my first teaching job of any kind. I read widely in the Indigenous and settler history of the central coast and Jo and I sent a reading list out to the guests. It included Beth and Ray Hill, Indian Petroglyphs of the Pacific Northwest (1974), Cliff Kopas, Bella Coola (1970), Bruce Ramsey, Rain People: The Story of Ocean Falls (1971), and Captain John Walbran, British Columbia Coast Names, 1592-1906 (1909). We received permission from the-then Bella Coola and Bella Bella Indian Band Councils to visit their lands. Jo wrote to me in April 1988:

I’ve approached people in Bella Bella and Bella Coola for tours, etc. Both requests met with considerable interest. The people at Bella Bella would like to put a couple of elders aboard for part of a day which would be terrific. I’ve asked for a traditional feast there, as well. Bella Coola contact suggested a hike up to some petroglyphs and storytelling with an elder. Sounds great. Nothing confirmed yet but looks good.[5]

*

The journey began at Port Hardy, near the northeast tip of Vancouver Island, on May 31 1988, and ended in Bella Bella on June 6. The guests flew or drove in from Vancouver, Seattle, and New York, and the Clavella’s crew brought the ship up from Nanaimo. I drove up-island from Pender Island, where I lived, a couple of days early to meet the crew and get acclimatized.

I stopped on the way at two places I’d long wanted to see: Fort Rupert and Telegraph Cove. Fort Rupert (Tsaxis) was the site of the HBC’s first venture into coal mining in 1849. The one coal seam – exposed on the beach in front of the fort — turned out to be of poor quality, and the HBC moved its mining personnel and equipment to the superior coal deposits at Nanaimo in 1852. Telegraph Cove, formerly the site of a salmon fishery and cannery, was one of many settlements on the BC coast devoted to salmon exploitation during what historians have called the “Great Potlatch” (Margaret Ormsby) and the “Great Barbecue” (Martin Robin) of natural resources in the few decades before 1914.

I met the guests and crew of the Clavella at Port Hardy after dinner on May 31. The crew consisted of John de Boeck (captain), Jack Pearson (first mate), and Nicky Smith (cook), all from Nanaimo. The guests were Jean Beatty (Vancouver), Mary Plumb Blade (Vancouver), Barbara Brown (Orcas Island WA), Eleanor Clifton (Friday Harbor, WA), Sara Jane Johnson (Seattle), Margaret Murdoch (Vancouver), and Barbara Prete (New York).

June 1, 1988. After breakfast the next day we headed across Queen Charlotte Strait for mainland British Columbia. Clavella, built in Vancouver in 1937, proved her seaworthiness in the rolling ocean swells we encountered off Cape Caution. Miraculously no one was seasick.

David Hill-Turner, who had worked on the Clavella before, had sent me what turned out to be an accurate heads up about the ship:

Apart from shore preparations, boat travel is a relaxed unstructured affair. The Clavella has a large wheelhouse where people can gather, there is a comfortable lounge and for the warm sunny days there are pew-like benches on the stern of the boat. Some people might be content to just rubber neck and have their questions answered, others will just chat and sometimes people just want to read or nap.[6]

A few hours later we entered Rivers Inlet on the mainland coast, once the location of the greatest concentration of salmon canneries north of the Fraser River, but now known for its exclusive fishing resorts housed in converted canneries. Fortunately a friend, Ed Higginbottam, had given me maps and aerial photos of the Rivers Inlet cannery sites, and I could provide names to clusters of pilings or rotten old wharves. The Rivers Inlet canneries – all long-gone – were Brunswick, Beaver, Goose Bay, Kildala, McTavish, Provincial, Rivers Inlet, Strathcona, Wannock, Wadham’s, Boswell, Le Roy Bay, Margaret Bay, Good Hope, Victoria, and Vancouver/ Green’s.[7]

We put in to the abandoned Goose Bay Cannery, then a fishing lodge, but were told by the caretaker not to set foot on the property. The owners had given him strict orders to keep the place private. The resort season had not yet started so we contented ourselves by cruising up and down the inlet in front of Goose Bay before going to Duncanby Landing further up the inlet. Formerly a cannery, this site was now a refrigerating facility owned by BC Packers of Vancouver. The couple who managed the place let us wander around and even opened their tiny general store for us.

We had hoped to go further down the inlet to Wadham’s Landing and Dawson’s Landing, but a storm was approaching outside and the skipper thought it best to go straight to Namu at the north end of Fitz Hugh Sound.

We reached Namu at dinner time. Owned, like Duncanby Landing, by BC Packers Namu was an ice station and cold storage plant for coastal fishermen. Most of this large town had been abandoned; schools, stores, and government offices pulled down or boarded up, some buildings still showing the green and white company colours. I was unprepared for the scale of the industrial remains. Blocks of devastated hotels and other wooden buildings, locked and disintegrating in the wind and rain, lined the waterfront on rotting pilings. Boardwalks still enclosed much of the shoreline. Grizzly bears lived in the woods behind Namu and sometimes wandered down.

Depleted salmon stocks and improvements in technology combined to put canneries on the central coast out of business in the 1960s, forcing non-Indigenous fishermen and their families to move elsewhere. In the old days, salmon was caught, sold, and canned locally while the fish was still fresh. Now, in 1988, salmon was preserved in ice produced at Namu and Duncanby Landing and taken to Prince Rupert or Vancouver for processing. Most was caught in the open sea; little came from the river mouths and coastal inlets.

This meant that there was no further need for canneries on the central coast, or for many workers, whether settler, Indigenous, Chinese, or Japanese, as in the canneries’ heyday. Namu is an extensive ghost town. Only a few families remain. I walked down to what looked like a natural beach beneath the docks and wharves, and found to my amazement that it consisted entirely of generations’ worth of eroded and broken bricks, glass, and rusted twisting metal. This would be an Eden for an industrial archaeologist.

This half a mile of water-worn industrial detritus was actually stained throughout the intertidal zone a uniform rust-coloured red with the occasional mottled green patch caused by discarded copper piping.

In the 1970s Simon Fraser University archaeologists found the remains at Namu of an ancient Indigenous settlement. I had written to archaeologist Philip Hobler of Simon Fraser University for more information. “There are 400 archaeological sites in the Bella Bella-Bella Coola part of the Central Coast,” he replied. “It is hard to know where to start…. Namu has the oldest dated archaeological site on the coast. People were living there at least 9720 years ago. Take your people up the boardwalk toward the lake and someone can point out the site.”[8] This site, the lower portions of which rested on glacial till, was located within a sprawling industrial ghost town that had not even existed a hundred years previously.

June 2, 1988.

We left Namu in midmorning of June 2nd and headed up Burke Channel — one of those “Majestic Fjords of British Columbia” marketed so effectively between the wars by the Union Steamship Company.

In the late afternoon we anchored near a logging show at Kwatna Bay, off Burke Channel. We learned from the ship’s library that the Native people of Kwatna were relocated, in the late nineteenth century, to Bella Coola and Bella Bella by the Department of Indian Affairs. The site still looked habitable. Where the meandering Kwatna River entered the bay was a wide delta, and at low tide mudflats and grasses made their appearance.

We took the small boat ashore to the logging camp, where the foreman showed us around his muddy and utilitarian industrial settlement. He told us that an abandoned logging railway can still be followed up the gentle valley floor, a remnant of an earlier era of coastal logging. His crew was working far up the Kwatna River. We watched a logging truck rumble in from the upper valley and drop its load near the water, where the logs were sorted and boomed before being taken to sawmills in the south.

I asked if Indigenous people still visited the river. The foreman hadn’t seen any, but he remarked casually that men from the camp had found and ransacked burial caves near the river mouth.

Thirty men were employed here, as well as an unfriendly mongrel whose job it was to keep the grizzlies at bay. With its trailers and its transient, cut and run, scorched earth premise, this community was meant to be the very opposite of permanent, unlike the Native community that had preceded it for about 10,000 years.

Everything about the camp was transitory. It was a textbook study in impermanence. The men, who lived in ATCO trailers, came by floatplane from the Vancouver area, where they left their girlfriends, wives, and children. They were lured north by short-term and high-paying contracts. When they had taken the last merchantable trees from their lease, the camp was closed, the men went home, they took their dog, trailers, and pay cheques with them, and perhaps in fifty years’ time another logging company will have a go at the second growth trees and burial caves in Kwatna Valley.

The Clavella was a well-known whale tour boat; John de Boeck, our skipper, was pleased when a photo of the ship appeared in National Geographic. We were thrilled to be able to follow a pod of killer whales down North Bentinck Arm to Bella Coola on June 3rd. John, Jack Pearson, and Nicky Smith knew the killer whales by name. Since it became illegal to shoot these creatures they have multiplied, and this pod was following the salmon up to the Bella Coola River.

At Bella Coola we were met by Jennifer Carpenter and a Heiltsuk colleague who took us to the Thorsen Creek petroglyph site. “The Thorsen Creek petroglyphs 2 miles from Bella Coola are excellent, a provincial reserve,” advised archaeologist Philip Hobler. “You would need a car and someone that knows the way as there are no signs.”[9] Here, high up, we visited one of the most impressive displays of Indigenous rock art on the continent.

Before we walked up the long road and trail to the site we received permission from a group of Bella Coola elders, who performed a roadside ceremony in their language. The elders asked us to form a large circle, join hands, and stand quietly while they explained the spiritual and cultural importance of the petroglyphs. This physical contact seemed to dissolve the formal relationship between tourists and Indigenous residents. They explained that the non-Indigenous owner of the site had recently hired a backhoe to dig trenches across the gravel road to keep trespassers off his property. We skirted the trenches and made our way to the petroglyphs.

The site itself was magical. A trail wound between the exposed bedrock, sections of which contained petroglyph panels. Thick moss covered much of the ground, and the air was filled with the roar of Thorsen Creek, which at that time of year was more like a river. It had cut for itself deep and clear pools in the bedrock of the creek bed.

On our way back to the boat we were taken to the Band’s new school and cultural centre. This magnificent building consists of three large longhouses built side-by-side with the inner walls knocked out or opened up to form spacious classrooms. The central longhouse is taller and larger than the other two and resembles the nave of a church; the smaller longhouses on either side are like church aisles.

Later, one of the tourists remarked that of course “they” wouldn’t have been able to build such a school without federal money, a remark that to me cheapened the whole enterprise and negated the kindness we’d been shown. And shouldn’t we congratulate “them” for using the sources of funding available to them, and for exhibiting some of the entrepreneurial spirit that is so valued in our society?

It was here that I first realized the full extent of the difference between those Native cultures and our own. Native societies and economies did not look to the outside world for their cultural and economic identity, such as we look across the 49th parallel for our popular culture, and in that Free Trade era, for economic salvation. The central coast of British Columbia is inhabited by a resilient, confident, and rejuvenated Indigenous culture existing alongside the detritus of a transient economic order that had already moved on to greener pastures.

June 4, 1988.

We were up early on June 4th and heading through North Bentinck Arm to Labouchere Channel and Dean Channel. We stopped briefly at the sulphuric hot springs at Eucott Bay, where some of us wallowed on the beach amid hot and salty mud and seaweed. From the forest on the other side of the bay several men emerged. We watched as they lined up a row of shiny metal pipes near the top of the beach. Later we learned that they hoped to turn the hot springs into a commercial venture.

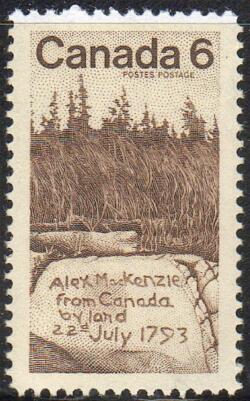

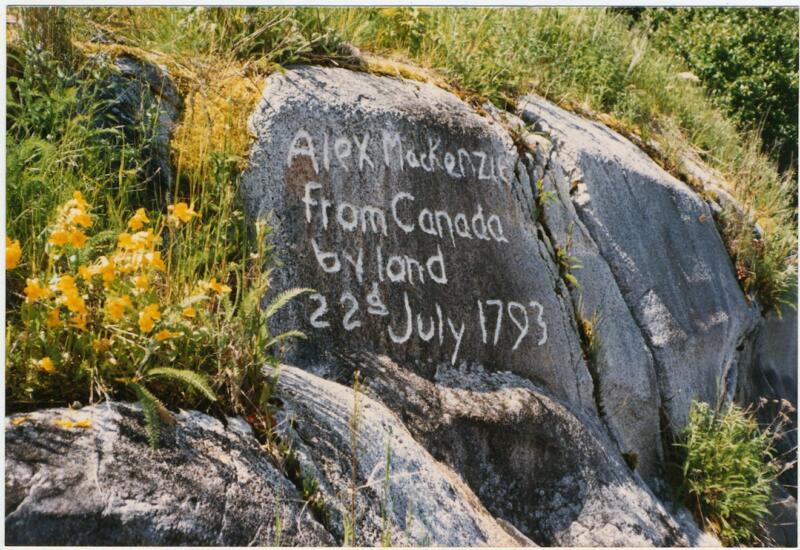

In the afternoon we reached Mackenzie Rock, half way along Dean Channel between Bella Coola and Bella Bella. I’d wanted to visit this site since I was a kid, when the rock appeared on a Canadian postage stamp. It was here that Alexander Mackenzie ended his transcontinental voyage, mixed some vermillion and grease, and wrote his famous inscription about reaching the Pacific from Canada by land in 1793. After scanning the channel walls with binoculars from the ship we located the site, and took the small boat ashore. Mackenzie Rock can only be reached from the water and is marked by a rusting cairn erected seventy years ago by the federal government.

The plaque states that this first transcontinental crossing was achieved thirteen years before the Americans Lewis and Clark made their crossing. This gratuitous display of old-fashioned patriotism — so foreign to a Free Trade era when continental integration was emphasized — left the Americans on our tour silent and puzzled. They had never heard of Alexander Mackenzie.

Not another boat was in sight. We knew we were the first visitors of the year because we had to beat a pristine path through a healthy crop of stinging nettles to the cairn and petroglyphs. We had been well prepared by Philip Hobler of SFU:

If you are going to Mackenzie’s Rock you will find the three petroglyphs at the top of the intertidal zone at the head of the tiny bay adjacent to the rock. They are some 40 m, as I recall, from the concrete monument. If your group is observant they may find the small set of concrete stairs leading up the back of the rock. The rock itself was an Indian fortified settlement typical of the central coast at the end of the 18th century. Large villages with rows of undefended houses (so characteristic of all of the archival photographs) are a development only of the later 18th century and were not observed by any of the early explorers. In 1983 I conducted archaeological excavations on top of the rock and found at depths of 1.4 m planks and joists of an early house floor dating some centuries before the historical period.[10]

Thus the deep Indigenous presence asserted itself again. Mackenzie had the good sense to make his final transcontinental camp at a location that had been occupied in the relatively recent past. We noted that the historic cairn did not even mention the Heiltsuk people whose territory included Dean Channel. Mackenzie could not reach the open Pacific because the Heiltsuk would not let him go through their territory.

Mackenzie’s inscription was known from his journal but the exact location of the rock remained unknown until the 1920s, when it was found by a government surveyor who made permanent what remained of the inscription by chiselling Mackenzie’s message into the rock face. Thus an eighteenth century pictograph became a twentieth century petroglyph. We found the three much older petroglyphs, mentioned by Hobler, high on the beach in the tiny bay behind the rock, forming one of the few physical unions of old and new cultures on the whole trip.

*

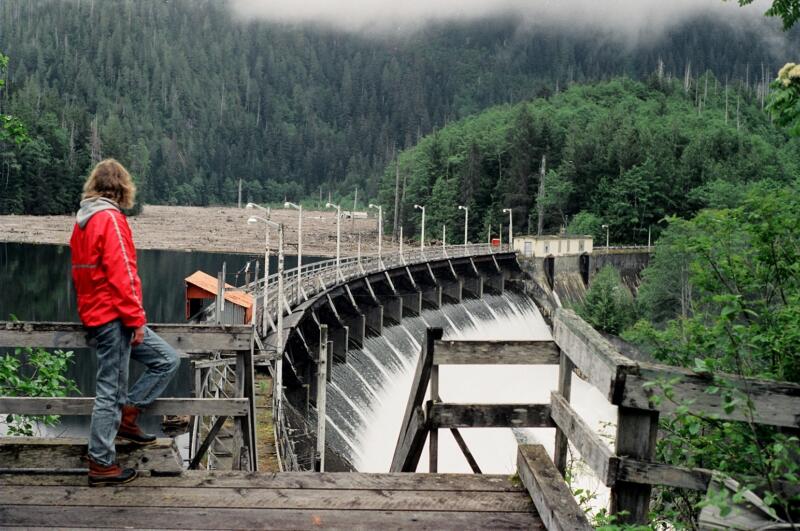

In the evening of June 4th we reached Ocean Falls, a company town built around a pulp mill that was operational by 1912. Subsequently it was owned by San Francisco-based Pacific Mills. By 1973, after seventy years of feverish production, new owner Crown Zellerbach closed the mill after towing pulp timber from as far away as the Queen Charlotte Islands. The provincial government then bought and administered the town and mill until 1980, when it too abandoned the place. In keeping with the reckless use of central and north coast timber resources, the lack of timber supply was the main reason for the closure.

The original company built two mills (pulp and saw) and a town site at the head of the inlet and dammed the Link River, creating the Link Lake Reservoir. Workers were hired on the south coast, and for three quarters of a century the town thrived. After 1945, Ocean Falls was a mecca for new immigrants to Canada, including DPs (Displaced Persons) from central Europe, and in 1950 the town reached its maximum population of 3,500.

A friend from Pender Island, who was born at Ocean Falls in the 1920s, assured me that when she was growing up there in the Depression, the town’s light bulbs were all stamped “Stolen from Pacific Mills” in case anyone felt light-fingered.

We had with us a history of Ocean Falls done for the 1971 provincial centennial. Bruce Ramsey’s Rain People: The Story of Ocean Falls told of the creation of the clubs, schools, societies, and churches that served the town’s needs. A full-page photo was devoted to a teenaged girl from Ocean Falls who won a swimming medal at a Pan American Games in the 1960s.

Yet we found little left of the society portrayed in Bruce Ramsey’s proud history. We were told that only thirty people still lived there. We encountered a sprawling industrial ghost town in the wilderness. Wooden houses, concrete hotels and apartment buildings remained, their windows smashed for several floors up, their gardens supporting miniature coastal forests. When Crown Zellerbach and the government left they bulldozed whole streets of houses of recent construction; they feared squatters, injuries, and lawsuits. We walked through the deserted streets, examined the gaping basements, the red paint peeling from fire hydrants barely visible in the forest next to the skunk cabbage, and realized that in another few decades the forest would have taken over much of the town.

The pulp mill, an abandoned factory many acres in extent, sat in silence while the water of Link River fell with a roar from the dam behind. This cascade lent a false sense of haste and activity to the town. The dam was still structurally sound — unlike the local version of the settler culture that produced it.

Something about the place reminded me of the sites where I worked during my six years of archaeology in British Columbia. It was the sad sense of emptiness and desertion, the quiet where there had once been voices, the absence of stories and the tangible printed word, the mute puzzles and riddles of cold artifacts of stone and, in this place, of concrete and rusted metal. I used to gaze down at communal hearths or structural post-moulds that were thousands of years old and wonder to myself, is this all we leave behind, this hard-packed, mottled, fire-stained earth? How can we translate the data derived from archaeological (or historical) surveys or excavations into accurate, suitable, appropriate words? And here at Ocean Falls I had the same sensation: I wanted to reach out, to understand the people who devoted their lives and life energy to this place until the pulp timber ran out and they dispersed.

Any settlement abandoned for long enough will become an archaeological site. Ocean Falls was well on its way to being one. The segment of settler culture that existed at Ocean Falls for most of the twentieth century had moved on. Settler culture still existed, but not here . There is no critical mass left here for a historian to get his teeth into. Who will write this history when Ocean Falls memories and photo albums exist in a hundred places, but not here?[11]

At Ocean Falls an Indian Reserve was annulled when the pulp mill licence was granted. The Native inhabitants were relocated to Bella Bella. An elder at Bella Bella told us that before the dam was built, Indigenous women used to pick berries on the Link River. When they returned for berries they found the river flooded. The surface of the reservoir was stained red with pollen that had drifted up from their berry bushes, which had continued to grow underwater. Link Lake also contained a submerged forest for many years: in their haste to build the dam the company hadn’t bothered to harvest or even fell the trees.

A dozen or so loggers and their families remained at Ocean Falls. They were cutting the second and third growth timber around the reservoir, the inlet, and the town. Much of this timber must have been left standing for aesthetic reasons.

Recently someone developed a scheme to export fresh water by tanker from Ocean Falls, but the plan floundered when it was realized that large ships would be unable to turn around in the narrow inlet. I reflected that in British Columbia, technology and capital yield only to geographical constraints.

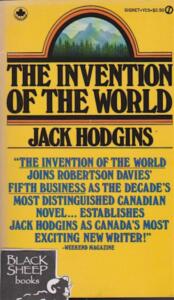

As an aside, I brought with me as reading material Jack Hodgins’ first three books: Spit Delaney’s Island (1977), The Invention of the World (1978), and The Resurrection of Joseph Bourne (1979). One of the tourists, Barbara Prete, devoured all three books — which are set in the stable rural communities of the Comox Valley on Vancouver Island, where mixed economies of farming and logging prevailed. Jack Hodgins grew up on a rural acreage at Merville in a family that logged, farmed, fished, and hunted; his father Stan, a member of the “Comox homeguard,” ran a yarder and later a steel spar for the Comox Logging Company. Jack Hodgins’ books are the kind of local literature that can form when generations of extended families put down roots and embrace the land — the very opposite of the unnatural abandonment and alienation of communities like Ocean Falls and Namu.

It turned out that Barbara was the executive director of the National Book Awards in New York City. She told me that if The Invention of the World had been eligible, it might well have won the competition.

June 5, 1988. At Bella Bella (Waglisla) on June 5th we were given much the same sort of hospitable welcome we had received at Bella Coola. We were met at the wharf by several elders and taken to the Heiltsuk Cultural Education Centre. We noticed that the Crown land surrounding this waterfront reserve had been clearcut.

Later, at McLoughlin Bay just south of Bella Bella, we visited the site of the HBC’s Fort McLoughlin, where from 1833 until 1843 the company maintained a fur-trading post. In 1843 the company moved their personnel and trade goods to Fort Victoria — their new post on southern Vancouver Island — which was been far more successful as a colonial settlement. The Heiltsuk set fire to Fort McLoughlin when the company moved to Fort Victoria.

We were given a tour of the Band’s new fish-processing plant at McLoughlin Bay, built with Japanese capital with the aim of processing fish and seafood caught in local waters. This shiny and efficient facility is built virtually on the location of Fort McLoughlin.

In the evening we were treated to speeches and to a feast of herring roe, salmon (smoked, baked, fried, and poached), potatoes, and oolichan oil or grease at a church hall in Bella Bella. At the end of the speeches I made a small speech on behalf of the Clavella and her guests. All I could bring myself to say was that we’d seen great desolation at the Rivers Inlet canneries, at Namu, and at Ocean Falls, and that our experience in those places contrasted strikingly with the viable Indigenous community structure at Bella Coola and Bella Bella.

I wanted to say that my experiences on the central coast had not made me proud of being a British Columbian. Twenty or thirty years ago, when those communities were still thriving, I might have thought differently; I might have assumed that a sustainable local timber supply might enable a longer community life. But how can one feel proud of a settler culture that allows its more remote communities to be reduced to rusted metal, bulldozed rubble, and industrial wastelands? When the people to whom it was home have left and put down roots elsewhere? When magnificent resources have been recklessly squandered?

As a teenager I hitchhiked through the Kootenay region of British Columbia. I saw ghost towns like Sandon and Cody that flourished and then fell with the fortunes of the hardrock mining boom of the 1890s. But I never expected to see such emptiness on the coast.

I could only conclude that wherever settlers and capital had obtained access to pulp and timber leases, to water and cannery licences, the result was the inevitable devastation of renewable resources. The role of government was to facilitate all this: to allow and administer access. Communities appeared that were fated to extinction and their inhabitants to eviction. Profits earned from those commercial and industrial undertakings did not go toward the creation of stable and permanent settler communities.

Canada is full of people, many of them quite young, whose birth certificates state that they were born at Ocean Falls or Namu, Ceepeecee or Tumbler Ridge, Rock Bay or Bralorne. Northrop Frye once wrote that “Canada is full of ghost towns, visible remains unparalleled in Europe.”[12] It is impossible to produce a distinctive or stable culture with such transiency. Local histories of these places might never be written; their existence has been curtailed and negated. What I witnessed on the central coast in 1988, according to the more recent analysis of UBC economic geographer Trevor Barnes, was the aftermath of “cyclonic staples extraction.” Company towns such as Ocean Falls and Namu, and hundreds of others in Canadian history, “enjoy rapid growth when a new resource is found, but are equally hastily abandoned when resources run out, or prices fall”

In opposition to themes of abandonment and loss of history is the more positive recent experience of Indigenous towns on the central coast. At Bella Coola and Bella Bella we saw schools, cultural education centres, and fish processing plants where renewable resources are directed for local consumption and export. Indigenous people are not about to disappear after 10,000 years of successful adaptation to changing coastal conditions. This is their home, not a “frontier” ripe for exploitation. In the meantime, only concerted conservation efforts will help restock the rich maritime and forest resources of this empty coastal corridor.

*

Richard Somerset Mackie started The British Columbia Review with Alan Twigg in 2016 after working at the journal BC Studies for five years as Associate Editor and Book Reviews Editor. He has an Honours M.A. in mediaeval and modern history from the University of St. Andrews. His essays for the BC Review include Old Friend in a New Land: English Songbirds in British Columbia (January 17, 2019) and Beyond the Great Western Peninsula (February 10, 2020). He lives in East Vancouver.

All photos are by Richard Mackie unless otherwise noted

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] I thank Jo Ledingham for all her work in making the 1988 tour happen. Philip Hobler, Jennifer Carpenter, Quentin Mackie, and Gunnar Tosten contributed generously. David J. Spalding of Pender Island provided help and input with the early drafts. Al Mackie, Brian McDaniel, Susan Safyan, Randy Eustace-Walden, and Graeme Wynn helped with subsequent drafts, revisions, and references. The analysis, opinions, and conclusions are of course my own.

[2] I finished my PhD in 1993 and published a revised version as a book in 1997: Richard Somerset Mackie, Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific, 1793-1843 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997). The Finlayson quote is from p. 69.

[3] For the rapid industrial assault (ca. 1910-1945) on the Douglas-fir coastal lowlands and lower mountainsides of central Vancouver Island, see Richard Somerset Mackie, Island Timber: A Social History of the Comox Logging Company, Vancouver Island (Victoria: Sono Nis Press, 2000), and Mountain Timber: The Comox Logging Company in the Vancouver Island Mountains (Winlaw: Sono Nis Press, 2009).

[4] See Quentin Mackie and Daniel Leen, “North Coast Rock Art: 30 new sites discovered in 1984,” The Midden 17:2 (April 1985), pp. 2-5.

[5] Jo Ledingham to Richard Mackie, April 12, 1988.

[6] David Hill-Turner to Richard Mackie, April 17, 1988.

[7] See Edward N Higginbottom, “The changing geography of salmon canning in British Columbia, 1870-1931,” MA thesis (Geography), Simon Fraser University, 1988.

[8] Philip M. Hobler to Richard Mackie, May 20, 1988.

[9] Philip M. Hobler to Richard Mackie, May 20, 1988.

[10] Philip M. Hobler to Richard Mackie, May 20, 1988.

[11] The answer to my question is, of course, Duncan lawyer Brian McDaniel, son of the doctor at Ocean Falls. See R. Brian McDaniel, Ocean Falls: After the Whistle. Recollections and Reflections of Life in a Coastal Company Town (Victoria: Printorium Print Works, 2018), reviewed here by Howard Stewart.

[12] Jean O’Grady and David Staines (editors), “Northrop Frye on Canada” [1976], Volume 12 in Collected Works of Northrop Frye (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003).

24 comments on “1523 Along the empty corridor of British Columbia”

Thank you, Richard! Always a pleasure to read your works!

Although I’ve only travelled the Inside Passage once (1976), and then as a summer student working on a Coast Guard cutter, your descriptions brought back childhood memories of exploring abandoned buildings around the telegraph station in Bamfield in the mid-1960s – the inside of the theatre was especially poignant, in light of your observations: the roof and floor were collapsing, it was overgrown by lush vegetation, and yet it was as if someone had just closed the door after the last film, and walked away – the seats were there, the film projector, and even canisters of old movies, with fragile film still in place. The abandoned and crumbling theatre just “didn’t fit”! This was in utter contrast to the erect corner-post of a longhouse not many miles away, half hidden under salal, which looked so natural and “at home”. I can relate, in some small way, to your contrasting observations. You were ahead of your time in recording your thoughts!

Keep well!

Hi Richard,

I put your Central Coast piece aside until I could find the time to do it justice. It’s very good and very good that you were able to share it with us, thank you. I hope you might find some way(s) to float it again, in other forums. It conveys such an important message about our modern BC economy, its excesses and contradictions that most of us continue to deny. Denial may grow more challenging as the climate continues to slip out from under us.

Howard Stewart

How utterly uncanny Richard to read your lovely writing today. Overgrown pallets pink roses are blooming, the doe and her fawn are browsing on fresh blackberry leaves, the Catalpa Tree is doing its classically late Salt Spring bloom and my thoughts are swirling after reading about Julian Wake’s passing. Which apparently was months ago. In fact two seasons ago. Then I dropped my thoughts into your inspiring piece which holds such wonderful thinking about my beloved Central Coast.

In 1987 my then partner and I charted a boat for the summer and fall season to explore the Inner Coastline with Haida Gwaii as our destination and summer/fall port. We headed out from Sidney with our shared four children (one still a baby under a year) and experienced a remarkable journey. We also took guests with us for most of the adventure. I could write endlessly on the very similar thoughts and reflections that you experienced. Somewhere there is a vast collection of photographs and negatives from the iconic Namu, Blunden Harbour, my beloved Butedale, and on and on and on.

That 1987 summer’s experience shaped my life. My always undisciplined creative mind clearly saw the tremendous interface that was actually occurring in slow-time right in front of my eyes. By this I mean the disintegration of the historical industrial Central Coast with the simultaneous cultural revitalization of Indigenous peoples. I still hold my memories of Butedale lit up at night with all that tremendous power flowing through the old penstock and into the generator building. It’s not much of a stretch to hear the ghosts of the First Nations band playing near the Old Bunkhouse, a Saturday Night in Butedale about to begin. Magical.

Somehow after reading your writing it seems so fitting to spend the day reflecting about Julian. I am so grateful Julian fished with my beloved father Walter Ernst in the Deena and Copper Rivers. I am so grateful that my children and grandchildren know the Coast from Salt Spring to the Haida Gwaii like the backs of their hands. I am so grateful Jack Hodgins’ books still are on our shelves. And I give thanks that yet another successful halibut season is behind my grandsons. And that their boat was blessed in Charlotte by those who have known the family for a few generations now. Yes, the Central Coast has changed. I used to believe all those hard working men and women of diverse cultures and ways, their lives and memories, were lost, discarded in that powerful contraction to the south. Now I see that change is constant. Nothing stops transforming, shifting, and altering. And the Central Coast always will always hold much for those of us who still seek.

RIP, Julian. Julian, I shall be thinking about your time on the Haida Gwaii today. Wish we could charter another boat and sail up the Inside Passage with you as an honoured guest. Somehow I think Richard may know the way.

A lovely read Richard. It almost seemed I was on that trip and seeing the coast through your eyes. Thanks for the view. While I have paddled the coast, even stopping in at Clam Bay where an old friend, John de Boeck , hosted us until the wind calmed down enough for us to make the crossing north a couple of days later, we didn’t stop in at the ‘industrial’ sites so I felt I hadn’t experienced that part of history. On the other hand, we, being mostly First Nations (with a few Non-indigenous paddlers like me) stopped at ancient or current village sites and were hosted by Nations along the way. It made me realize that there were two coasts, one navigable by canoes and another by boats, one with beach landings and one with deep water wharves and they are two different worlds.

And thanks for bringing the Clavella back to life. I remember her from when she sank, was salvaged then rebuilt and John tended her for her new role. At the time I deck-handed on the Argonaut II, another wooden classic coastal boat.

Wonderful remembrance of a remarkable voyage, you’ve captured both the extractive mentality of BC’s ‘frontiers’ , and the timeless connections, come hell or high water, of the first people who’ve lived on this coast since back in time. Moments described and photos shared have captured bits that are with me forever — particularly the generous feast at Bella Bella, ‘Kwatna then and now,’ Thorsen Creek, and Mackenzie Rock. Thank you for publishing, Richard. David Hill-T and I are in touch, and almost neighbours in fact… I hope you are well and happy. PS do you remember our conversation about a ‘possible HBC structure’ (with hewn-log dove-tail corners much like the HBC fort in Ft St James) which I stumbled across while anchored up on Banks Island? Did you ever learn more about that? At the time, you thought it may have been an abandoned post from the early-mid 1800s, and would check.. Cheers! John

Additionally, Clavella and I enjoyed 23 great years of coastal exploring — eight before and fifteen after this trip — and covered about 330,000 nautical miles along BC’s waterways. Clavella retired in 2003. Since then, I’ve been based in Queen Charlotte Strait, sharing time with divers, photographers and whale-watchers. Here is a link to my website, if I may. So, yeah, I’m still not really working — and haven’t for over 40 years!

Thanks, John, for this additional info. I’ve often thought what a serious undertaking it must have been to run and maintain a substantial vessel like Clavella. I hope your place at Browning Pass is easier to maintain — but that might be wishful thinking! Anyway, great to hear from you and hope to see you again. Best, Richard

Thanks, John, what a nice surprise to hear from after all these years! As captain of the Clavella, you were the guy who made the trip happen and we were all along for the ride. I remember your enthusiasm and the help you gave David H-T and me and the tourists. About the possible HBC structure on Banks Island, the HBC by and large didn’t build single structures in isolated locations, so the log house you saw with the distinctive construction was perhaps not an original HBC building — BUT it could well have been built by an ex-HBC employee, who carried on using the techniques they knew best in to the late 19th century at least. And they were prone to do so when milled lumber was unavailable. You might ask someone at the Prince Rupert Museum. Did you take photos by any chance?! Best for now, Richard

Richard, this ‘memoir’ is still a wonderful and colourful work of regional history, rich with insight and passion. It was a joy to become reacquainted with it. It makes one wonder (perhaps ‘shudder’ is a more appropriate term) what those areas look like now, almost 35 years on. As a side note, I’m sure that Grumman Goose is from the same fleet I flew in from Terrace to Masset in the Haida Gwaii back in 1980; a trip there and back I shall not soon forget.

Hi Randy, always good to hear from you, and thanks again for helping retrieve the photos used in this essay. On the topic of seaplanes and Grumman Geese, they were essential in getting into and out of Ocean Falls, and Brian McDaniel has a section on air transport in his recent history.

Thanks for letting us read your essay, Richard. In 2016 I spent a magical week on board The Swell on the waters of the Great Bear Rain Forest. When I was researching my book on Italian Immigration to British Columbia I became friends with an Italian man who spent 18 years in B.C. before returning to Italy. When he worked at Ocean Falls in the 1950s his favourite activity was to go alone into the mountains where this man from a crowded and poverty-stricken country could experience for the first time the unique feeling “of being where perhaps nobody had ever been before.”

Hi Lynne, I wondered if you’d made contact with the Italian community at Ocean Falls. They were great characters. One of them was the first cousin of a man who became Pope. Another was called, I think, The Count and dressed to the nines every night for dinner — though he worked in a pulp mill. Brian McDaniel has a section on the Italians of Ocean Falls in his recent history.

What a great article. Only someone with your deep knowledge of the coast could write this. I want to take this trip. Beautifully written, with profound knowledge and understanding.

Good to hear from you, Ray. I blush at your compliments. But I’ll take them

Great piece, Richard, which I’m pleased has finally found its way into print. How anyone could object to what you’ve said puzzles me. I came down the coast on a Canada Packers fish boat in the summer of either 62 or 63 and certainly witnessed much of what you discuss. As Theresa says, a layered and complicated place. I would add, confused and confusing. Also pleased to read the acknowledgement of Jack’s writing.

Yes, wasn’t the bit about Jack H’s book lovely? Sometimes it takes a person from outside to see the value…

Thanks, Ron. I don’t think my first few drafts were very well-written and I probably sent lousy photocopies of B & W photos to publishers. Now it’s digital everything, colour scans and the crisp layout of WordPress, and far easier to package a piece of writing in an appealing way than in 1989. And Theresa, yes, Barbara Prete lost herself in Jack Hodgins’ books, it was so good to see.

Great read Richard. I feel your pain in waiting so long to have it published. It would be great to have a companion piece on what it is like now. We celebrate so much the rape and pillage of non-renewble resources – such as gold. Thanks for this.

Thanks, Richard. I also wonder what it’s like now. A few years ago I worked with Brian McDaniel on his history of Ocean Falls and my sense is that people keep coming up with ideas to make a fast (or even slow) buck there — but the isolation of the central coast, the lack of roads in much of it, puts a brake on most schemes. And judging from Google images, Ocean Fall and Namu have not changed much since 1988, though Brian’s book shows that the pulp mill has been demolished at last.

Richard , while looking for a review of The Acid Room I found this. Great stuff. Once again I am reminded that I chose the best possible editor for “Ocean Falls: After the Whistle”.

Best regards

Brian McDaniel

Thank you, Brian! I was just going to send you a link. I enjoyed editing your fine book, Ocean Falls: After the Whistle. Recollections and Reflections of Life in a Coastal Company Town (2018), reviewed by Howard Stewart. Our review of The Acid Room has arrived and I will post it in the next week or two. Best, Richard

What a perfect thing to read on a summer morning, listening to ferry traffic from Powell River pass by. We live in such a layered and complicated place…

Thanks, Theresa. Layered and complicated is right I’m just lucky to have my own digital platform to air my radical and outlandish views .

.