1510 Truths from Tahltan & Tuscany

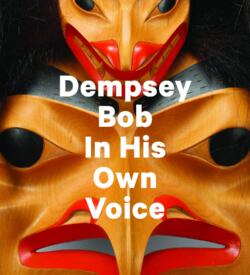

Dempsey Bob: In His Own Voice

by Dempsey Bob, with a foreword by Sarah Milroy

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2022, in collaboration with the McMichael Canadian Art Collection & the Audain Art Gallery

$40.00 / 9781773271613

Reviewed by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

*

I flip open the Dempsey Bob in his own voice book and I am staring face to face with The Eagle Forehead Mask (p. 131), one of Dempsey Bob’s carvings. I am drawn in by the lines of the eyelids. They are simply carved, yet complicated. They are holding back not just the eye but a careful thought.

I flip open the Dempsey Bob in his own voice book and I am staring face to face with The Eagle Forehead Mask (p. 131), one of Dempsey Bob’s carvings. I am drawn in by the lines of the eyelids. They are simply carved, yet complicated. They are holding back not just the eye but a careful thought.

For some strange reason a childhood memory comes to me, of hiding in a tent to read the book The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone, a book according to my parents that was totally unsuitable for a child my age. I am sure I must have skipped large swatches of the heavy text but I do remember being totally immersed in the emotions evoked by the text on the momentous life and powerful, passionate works of Michelangelo. We were camping at the beach in Tirrenia, Tuscany, Michelangelo country. When we weren’t at the beach, we were in museums, marble quarries, galleries, piazzas, palaces and churches. Michelangelo was everywhere.

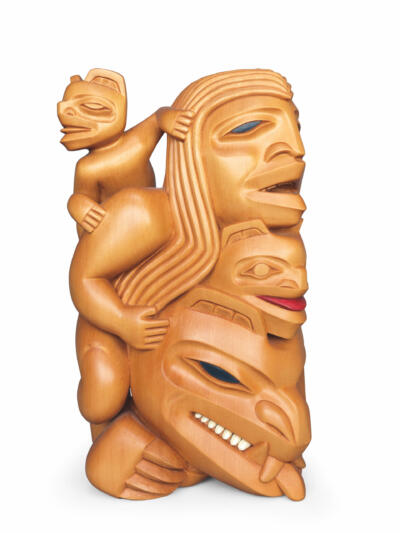

I flip to another page in the Dempsey Bob book and pause at the photo of a 3-dimensional carving Rain Frogs (p. 159). Another line of an eyelid captures my attention. Never before has the lines of eyelids captivated me quite the way these ones do. Once again, it is the exquisite line of the eyelids that say so much.

Dempsey Bob’s carved eyelids are superb, often paired with mouths that speak of a compelling spirit within — Bear Mother for example, who looks as if she has just given birth to a bear cub who is yearning to see, emerging out from behind her (p. 158).

Deceptively simple lines, elegant, dignified, plainspoken lines that convey so much.

This is a book I knew I had to read to find out how the artist brought out the spirit hidden in the wood, much like Michelangelo brought out the figures hidden in the marble blocks of stone.

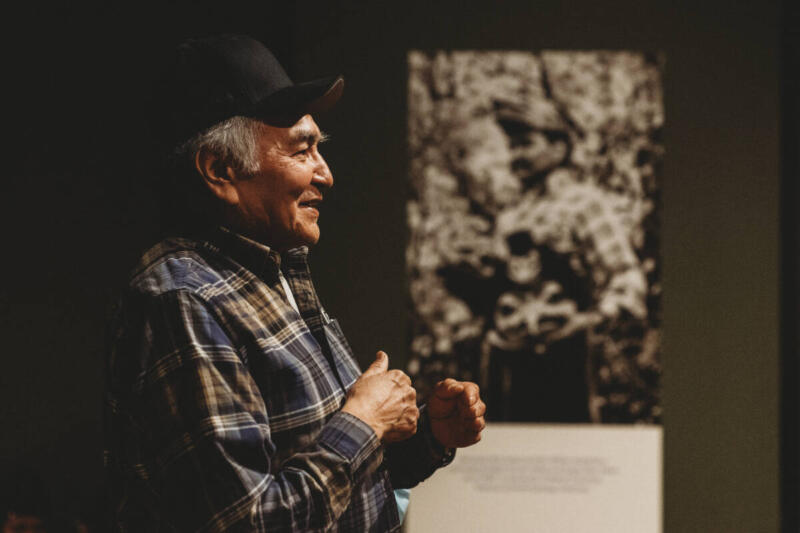

The hardcover book is based on interviews with Dempsey Bob, a Tahltan-Tlingit artist, conducted and transcribed by Sarah Milroy, Chief Curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. But, as the book title states, the words are in his own voice.

The book is the result of a collaboration between the artist, Milroy and Curtis Collins, Director and Chief Curator of the Audain Art Museum. It is intended to be a companion to the current touring exhibition Wolves: The Art of Dempsey Bob now showing at the Audain Art Museum in Whistler.

The book is over 200 pages and is beautifully illustrated with his sculptures and art as well as with photographs, many of them Bob’s personal photos illustrating his life. The 1893 photograph of his great-great-grandfather Étmatá and his grandfather, starts it off with Bob placing himself in his family and clan, his ancestry and the times they lived in.

It is about life, love and loss. Traditional names passed down through the ages, names like Étmatá whose meaning “got lost with the sickness.” Regalia, like the one his grandfather is wearing in the photo with the apron collected by George Emmons in 1900, and his grandfather’s shirt now at the Royal BC Museum. Regalia all gone from their homeland. His other great-grandfather carved spoons, masks, small totem poles, now all gone “All of that is lost now, like so many things.”

His grandparents grew up 270 miles apart from each other necessitating dog sled visits in bitterly cold weather. His grandfather described it succinctly: “Boy, was I in love!”

Dempsey Bob’s family moved from Telegraph Creek to Prince Rupert, to avoid Bob from having to attend the local residential school. He writes simply, “Bad stuff happened there.”

He is sparse with his words and with his carved lines, but they both convey deep meanings and encase strong emotions equally well.

As I read, I am getting a sense of what is behind Bob’s artistic drive.

In describing life and music in the 1960s and his love of the blues, he writes, “To make really true great art … if you didn’t live it. It isn’t real…. You have to earn it with struggle and hard work.” You can be technically perfect but it [the music] would have no soul. I suspect that is also how he sees his art.

When he was learning to carve with master carver Freda Diesing, he also had to learn to draw “because sculpture is all about the lines. As artists we look for the magic line. That’s what gives it life. You have got to live that line.”

I think he found the magic lines of eyelids and I get the feeling he lived every eyelid line he carved.

The book is not just about Bob’s art, it also chronicles his life, and as you read, you start to understand what life was like in the northern half of the province in the last half of the 20th century where one was expected to grow up and get a job at the local mill, or cannery, a life of logging or fishing. And what it must have taken not to go that route, and instead commit himself to art.

“I did it for my people and culture.”

The book is richly illustrated with Bob’s carvings. They are not 2-dimensional carvings bent into a 3-dimensional shape. If such a thing exists, I would say they are 4-dimensional because they contain a force within the sculpture, that “being” that the eyelid line contains.

Bob talks about some of his sculptures as beings: his girlfriend the frog woman who was her own self; the frog who made his own way in the world; the smart one who looked right at him stopping him in his tracks.

“Holy shit, he’s there!”

Bob talks about those who taught him. The basket weaver who showed him how to draw an eagle beak with just four lines — the right four lines. The wolf with their flowing movement lines and whose eyes are so important, he has dreamed them. What the animals teach about hunting or disappearing salmon, food of so many creatures.

It is interesting to read that in the 1980s when he started to show his work and become known, Indigenous people weren’t really allowed in art galleries (this in the 1980s!).

Once known, he started to travel to teach and to learn more. He went to the mecca for sculptors — Tuscany. He too visited the quarries, the foundries, the studios, and the works of Michelangelo.

Dempsey Bob’s book also has teachings for us mere mortals, warnings of cultures being lost, of the importance of passing on our values, of how stories are teachers and have meanings, and how we need to pay attention to those stories before it is too late.

Now, having read and viewed the book, I am compelled to go to the Audain Art Museum where the first retrospective of his work from the 1970s to the present is on until August 14, 2022: Wolves: The Art of Dempsey Bob. I want to see those eyelids in person.

*

Retired from Vancouver Island University where she held the position of Director of Research Services, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa now spends much of her time studying Coast Salish textiles. Along with a MA in Educational Technology, she holds a Master Spinners Certificate. She is a Research Associate with the Smithsonian and with VIU. She has worked with various museums including: the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the RBCM, MoA and the Burke Museum in Seattle in helping to identify yarns, fibres, tools and techniques used to create the yarns. She was instrumental in identifying a rare blanket in the Burke Museum confirmed to be made of woolly dog hair. She has given many presentations and workshops on the subject of Coast Salish spinning and textiles to Coast Salish spinners and weavers and has written articles on the subject for magazines such as Selvedge, Spin-Off, and Ply — and for BC Studies about the use of diatomaceous earth in Coast Salish blankets. She lives on Protection Island, BC, in Snuneymuxw territory. Editor’s note: Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa has also contributed an obituary of Bill Holm and reviewed books by Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse & Aldona Jonaitis and Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, & Willard Joseph for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1510 Truths from Tahltan & Tuscany”