1491 Be brave in giving

The Caregiver’s Companion

by Patricia Jean Smith

Oakville, ON: Rock’s Mills Press, 2022

$25.00 / 9781772442441

Reviewed by Betty Jane Hegerat

*

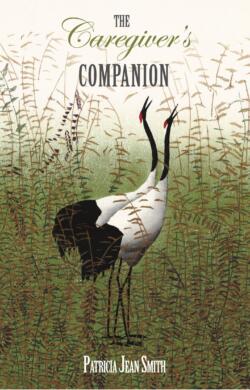

The cover of The Caregiver’s Companion by Patricia Smith is graced with an image by Chinese print maker, Hao Boyi, of two Manchurian red-crowned cranes. These birds are rare and endangered. To imagine one of the pair broken, the other left to fly alone, is painful, and evocative too of the human reality.

The cover of The Caregiver’s Companion by Patricia Smith is graced with an image by Chinese print maker, Hao Boyi, of two Manchurian red-crowned cranes. These birds are rare and endangered. To imagine one of the pair broken, the other left to fly alone, is painful, and evocative too of the human reality.

To write as Smith does, about life going sideways when her husband of forty-four years suffered a massive stroke in 2012, takes courage and unflinching honesty. After Ron Smith wrote about his recovery, still ongoing, in The Defiant Mind: Living Inside a Stroke [reviewed here by Mark Forsythe — ed.] Patricia was often asked if she had written her side of the story. She says that not until 2018 did she feel she had the physical and emotional strength to write The Caregiver’s Companion, not as a training manual, but as a companion, a compassionate ally for others who find themselves abruptly cast in the role of caregiver.

Part One of The Caregiver’s Companion begins with a description of “life before” and moves clearly and calmly through the brain attack and the learning that followed. There is a conversational flow to the writing that gives the sense that Patricia Smith is someone from whom there is much to be learned at a personal level. She says, “Ron and I were acutely ignorant of stroke and all it entailed.” In their encounters with other patients, they found that most of them were just as ignorant of stroke. As difficult as it is to imagine being either the afflicted partner or the caregiver after traumatic injury or illness, the insights offered in The Caregiver’s Companion are perhaps as valuable as preparation for the possibility, as they are to someone already caught up in the trauma.

In one of the many books Smith read about stroke and survival, the author said she gave all those with whom she was involved the advice to “expect full recovery.” This became the caregiver’s mantra. These two well-educated people, fully engaged in work and a rich life and hopeful about the future, were suddenly headed toward an unknown destination. The mantra was a new hope for the future.

Smith writes of how they were surrounded at every stage of treatment by medical professionals and staff, and their strong network of friends and family. She talks about her deep sadness for the patients who were alone. Support and encouragement seemed essential to recovery. The Caregiver’s Companion offers suggestions for resources to fill the gaps that are suddenly huge when the period of assisted recovery is over.

In describing her husband’s fear and depression, the state of his mind surely influenced her own, but Smith does not dwell on her own emotions. She talks about a Stroke Recovery Society, where both she and Ron discovered the bond between stroke survivors, and the similar bonding among caregivers. So much in this book emphasizes the importance of support and engaging with others. It is not a training manual, but the story it tells suggests a multitude of ways to make the journey as smooth as such a journey can be. Smoothness, however, is a relative term, and at the end of Part One, Smith has found that the mantra, Expect full recovery has become fainter. A louder, more urgent voice has taken its place — I Need a Break. I Need a Break. I Need a Break.

Part Two is titled “The Hero With a Thousand Faces.” Patricia Smith kept a record of the adventures she and Ron had after the publication of his book. She wrote them in the form of a blog, The Defiant Mind Journal. The original blog posts, along with insights and afterthoughts, comprise this section of the book. Publication of The Defiant Mind elicited invitations to speak and attend conferences and collaborative projects that took the Smiths to: Stroke Recovery Groups; groups of hospital administrators, therapists and nurses who work with stroke patients; conferences; everywhere there was interest in the book, and more importantly in meeting the people who owned the story. This part of the book is rich with letters or descriptions of encounters with others who were living new roles post-stroke. Simply reading the extent of the travels and imagining undertaking such an itinerary left me in awe. And exhausted.

Although her book was not yet written, Patricia was there throughout the tour to provide the experience of the companion, the caregiver. As I read Part Two, I was grateful yet again, that her story is now in print.

Part Three, “Mind Matter Body and Soul,” expands the wisdom in this book beyond the individual and specific crisis to the universal. In the first chapter, Smith continues to reflect on what it means to be a caregiver. She becomes more specific in describing the emotional reactions — so similar to the model of stages of grieving — that brought her to an understanding that caregiving is a part of our being.

The first chapter in this section is introspection on the full meaning of giving. Smith talks about a course in Religious Studies during her university years that led to a much longer search for knowledge about the differences that goodness and the good life mean in diverse cultures and civilizations.

The second chapter in this section is titled “Suffering.” Here Smith writes at greater length about how the true nature of mind and matter is asserted in Hinduism and Buddhism, and the concept of “flow,” and the ways it can be achieved. As insightful and well-researched as this chapter is, it was the one place in The Caregiver’s Companion, where I became less engaged, because it became more based in information than experience.

Similarly, the third chapter, “Duty,” explores the links between the mythology of a culture and language. There is a lengthy account of the tale of the Bharata dynasty, which I have no doubt was an insightful tool in Smith’s search for a deeper meaning to the word “duty” than most of us are inspired to, or required to seek.

In the remaining chapters, “Wilderness,” “Matter,” “Mind,” and “Soul,” the reflections turn to the universal tendency to take rather than to give, and to ignore caregiving as essential to the health of the planet. Here Smith makes interesting comment on climate change as a pressing feminist issue. It was in these final chapters that I found much to reflect on about caregiving on a huge and necessary scale.

This personal account by Patricia Smith of her discovery of who she became as she redefined her role as a caregiver is both clear and pragmatic and at the same time deeply moving. “Expect full recovery” becomes re-defined as “expect a new normal.” I found it impossible to read this book without acknowledging the possibility of a sudden “sideways slip” in my own life and reflecting on how well equipped I would be as a caregiver, or as a survivor. I take heart in Smith’s belief that caregiving is a part of our being. I take heart as well in knowing that other readers will find hope in this brave sharing. That many who need exactly such an ally, will find her in these pages.

*

Betty Jane Hegerat, a social worker by profession in earlier years, is a Calgary author, teacher and mentor. She has published five books: two novels, a collection of short fiction, a work of creative non-fiction that is a blend of fiction, investigative journalism, memoir and metafiction, and a novel for young adults. Her first love has always been short fiction and she is currently working on a new collection. She was the 2015 recipient of the Writers Guild of Alberta Golden Pen Award for lifetime achievement in writing. Editor’s note: visit Betty Jane Hegerat’s website here.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1491 Be brave in giving”