1465 Dark Wry

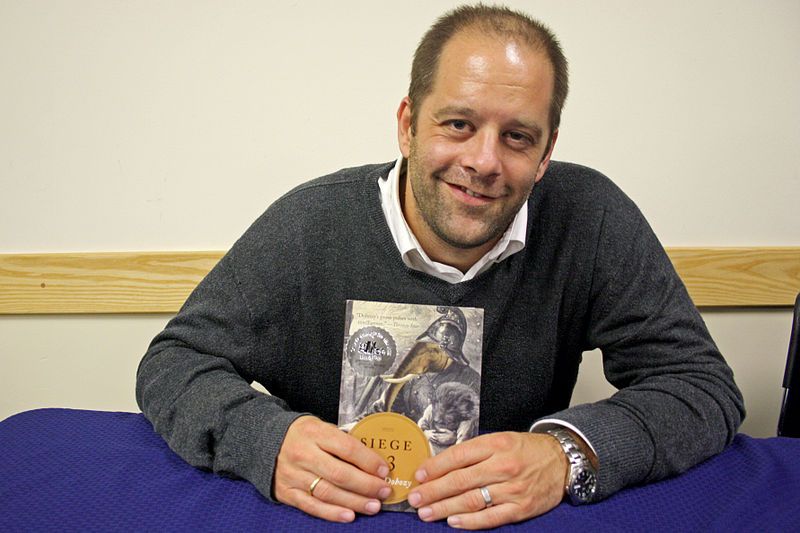

Ghost Geographies: Fictions

by Tamas Dobozy

Vancouver: New Star Books, 2021

$24.00 / 9781554201792

Reviewed by W.H. New

*

First off: Tamas Dobozy is a friend, so I’m not completely impartial. But I’ve now read this collection of stories three times, and each time I’m more impressed. This is a major book: serious, wryly humorous, carefully – artfully — written: passionate to come to terms with survival even when all experience argues that it’s an irrational goal. The book is not an easy read. Some might say it’s a ‘dark’ book: there is violence here, malice, cruelty, contempt — but there’s also a kind of love and something that might be called art and an absurd logic and surreal beauty. What’s its role? To draw the difference between a personal answer to the question of how to live and the directive that’s exerted by the state. The difference is critical. The book probes a human need for meaning; it’s also disturbed by what it finds out, asking if, in its quest, history can ever rise above paradox.

First off: Tamas Dobozy is a friend, so I’m not completely impartial. But I’ve now read this collection of stories three times, and each time I’m more impressed. This is a major book: serious, wryly humorous, carefully – artfully — written: passionate to come to terms with survival even when all experience argues that it’s an irrational goal. The book is not an easy read. Some might say it’s a ‘dark’ book: there is violence here, malice, cruelty, contempt — but there’s also a kind of love and something that might be called art and an absurd logic and surreal beauty. What’s its role? To draw the difference between a personal answer to the question of how to live and the directive that’s exerted by the state. The difference is critical. The book probes a human need for meaning; it’s also disturbed by what it finds out, asking if, in its quest, history can ever rise above paradox.

Read this book cautiously. Read it slowly. An artful education, Ghost Geographies is a searing political fiction. The tangles of desire are here; so are the shackles of human menace. But most of all this book cares. Loving what language can do and knowing that language is deceptive, it will reward a careful — and caring — reading.

At the centre is Hungary, its hundred or so years of war. We hear of the fascism that rises to replace the communism that replaces the empire that replaces the next in line before and after: no one design of power appeals to everyone, and some power apparently appeals to someone — hence the dilemmas the characters find themselves constricted by. The public monuments are often beautiful, but the history of power is not pretty, and nor are the stories that these extraordinary characters live. In the first story, ‘The Hobo and the Archivist,’ one character’s desire to document everything in a single archive is a compulsive sign of a utopian desire. But when the character, Wuyts, is invited in 1936 to move to Hungary and enjoy a perfect order (money, home, woman, opportunity) — and accepts the offer — he is misled: the invitation is not real, the order is not real, even power is not real, or at least it’s transitory, awaiting a replacement. In Wuyts’ apparently orderly life, the death of the Power Figure means upheaval, and all that is left is the shape of order, emptied of meaning. Ordinary characters laugh. They already knew what would happen. How do people cope with such fantasy? By appreciating the absurdity of their lives. Which is the same thing perhaps as politics.

There’s a character in this book — is it selfishness? or ‘perfect selfishness’? or even a fair characterization? — ‘who needed to believe in something better than what he suspected.’ There’s another character who leads an orchestra and draws something beautiful out of a performance but is irascible, violent, dictating ‘obedience’ above all else — which leads an observer to ask: if obedience leads to pleasure, is a dictatorial regime benevolent? And what are its other consequences? As with other stories, Dobozy’s characters ‘taunt us with contradictions.’ ‘Ray Electric’ asks what ‘amnesty means’ when the guards change colours? ‘The Glory Days of Donkey Kong,’ wonders what the role of a judge is in an autocracy—is it revolutionary? (what is ‘the role of a revolution?’) — and what is the function (or indeed the possibility) of ’a real conversation’ in an absolute state? ’Four by Kline Caro’ portrays a film about street kids and about rats eating each other, leaving open the difference between history and metaphor. For the characters, this distinction poses a challenge; is recognizing this difference enough to justify a story — because it exposes reality — or does it constitute an exercise in the pornography of violence? These are serious questions, not to be taken as casual exercises.

Repeatedly, characters draw maps, outline perfection, and fall into nonentity or disrepair. A professor who wins prizes galore, for example, finds out that honours mean little, till the story depicts him as nothing more (or less) than an ‘action figure,’ ‘a stutter’ that may or may not have the same value as a piece of Delft Blue. In a range of other stories, characters run up against signs, letters, fences, wire springs and boundary lines (in Canada and the USA as well as in Hungary): are they real, they ask (as the writer also asks) or are they simply — ‘simply’? — power markers? Is what they’ve written art—or is it a stutter? Inside such stories, characters may understand the stutter—may even attach meaning to it, identifying with the lapse — but the reader understands even more. Writing about history and politics, Dobozy is also writing wryly about fiction itself, asking what lasts, what is of value, what is real.

Sardonic humour governs other stories as well. A woman who can’t cope with the Canada where she and her family have resettled discovers that resettlement equals unsettlement, and so in reaction she goes searching for the ‘reality’ of the artifacts of the beautiful Austro-Hungarian Empire of history and myth. But what she finds, and shares with her children, is a rubbish tip. In an absurd world, she identifies the rubbish with the artifacts she remembers — to the point that her children, too, accept the alternate reality. A lesson is implicit here: exaggerating the beauty (or truth or even promise) of the past can do more than encourage nostalgia: it can distort the expectations of the next generation as well, till the children of the children of an empty empire can start to equate desire with emptiness. Or go searching in emptiness for whatever they think (or have been told) is what they desire — a cautionary start to any affirmation, but not an unfamiliar one, as in a later story, one that gives the book its title. What Dobozy calls ’ghost geographies’ draw maps of vacant lots, maps that privileged academics and underprivileged children can alike equate with a kind of art: a clear but ironic gloss on the identification of utopia (perfect place) as eutopia (no place).

The extraordinary impact of Ghost Geographies is that the stories, even while they’re wrestling with ambiguities and inexactitudes, always deliver to the reader some insight into history, some revelation about behaviour, some shade or shape of character. The ability of Powers to perpetuate untruths in the name of a perfect illusion is not unknown to anyone interested in the dynamics of history. Finding a book of narratives to brings these untruths into the light — to make political ideas reverberate not just in treatise but in the torn and wry and magnified and somehow radically familiar lives of vivid individuals — is a rare achievement.

That’s why I call Ghost Geographies a major book. It’s a book that thinks. Read it. Perhaps with horror — but if you do, appreciate at the same time its deftness of style, its imaginative reach, its awareness of the absurdity of human desire. I’m in awe.

*

William New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. He is also the author of a dozen collections of poetry, including The Rope-Maker’s Tale (Oolichan Books, 2009), Neighbours (Oolichan, 2017), and In the Plague Year (Rock’s Mills Press, 2021, reviewed here by Gary Geddes). Editor’s note: William New has recently reviewed books by Rhonda Waterfall, Leah Ranada, John MacLachlan Gray, Bill Stenson, Jack Wang, Michael Kenyon, and David Bergen for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1465 Dark Wry”