1454 Clicks and jokes and uproar

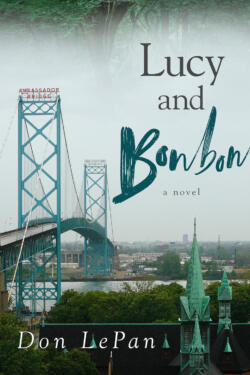

Lucy and Bonbon

by Don LePan

Montreal: Guernica Editions (Miroland): 2022

$20.00 / 9781771837187

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

Lucy and Bonbon unfolds in intriguing stages, each one with characteristics true to the genre. Though the novel’s irreverent conceits — bestiality, unnatural spawn — are the foundation of the premise and might provoke the torches-and-pitchforks crowd, a trio of storytelling techniques energizes Don LePan’s unique tale. Variously breakneck, inquisitive, and literarily playful, Lucy and Bonbon showcases an author who’s as assured with Big Questions as with the nuts and bolts of complex narration.

Lucy and Bonbon unfolds in intriguing stages, each one with characteristics true to the genre. Though the novel’s irreverent conceits — bestiality, unnatural spawn — are the foundation of the premise and might provoke the torches-and-pitchforks crowd, a trio of storytelling techniques energizes Don LePan’s unique tale. Variously breakneck, inquisitive, and literarily playful, Lucy and Bonbon showcases an author who’s as assured with Big Questions as with the nuts and bolts of complex narration.

In reverse order of appearance, LePan writes a version of a prison-escape narrative with assorted figures of power and authority — momentarily outfoxed but closing in — on the heels of frantic freedom-seekers and the hopeful Samaritans assisting them.

Preceding that, the author works within a ‘the novel of ideas’ framework that’s keen to explore philosophical and sociological matters. Nanaimo-based novelist (and Broadview Press CEO) Don LePan gave thought to similar material over a decade ago in his first novel, Animals. That singular dystopian vision presented a Swiftian new normal where the consumption of ‘lesser’ humans has become the current fashion. Animals explored our hierarchical, self-serving attitudes toward mammals with its portrait of a society that makes exceptions for widespread behaviour by rationalizing an appalling status quo as both necessary and beneficial. (A side note: having taught Animals for a couple of semesters, I can attest to the heated reactions and pure ire the novel drew from offended students, which ranged from disgust at the very notion of a novelist presumed to be exploiting developmentally-challenged characters in order to sell books to anger that someone would challenge a divine order in which humans were given dominion over animals from God. Lucy and Bonbon will intrigue and outrage in equal quantities, I imagine. In place of the cannibalism of Animals, LePan’s latest offers cross-species sexual experience — of all things, a ‘casual encounter’ one night in the Congo — and a mixed-species offspring whose bumpy reception in the world leads organically to the novel’s ‘prison break’ sections.)

Initially, however, Lucy and Bonbon highlights its status as self-reflexive fiction, complete with footnotes and a jumble of nested narratives from diverse media. The opening page, in fact, introduces an unnamed editor, an academic of some stripe based on the tone, who presents miscellaneous accounts — a “collection of excerpts” that includes transcribed handwritten notebooks, editorial asides, a testimonial, an “excerpt from the popular press,” snippets from assorted interviews, a controversial narrative (a “manuscript that has not been authenticated”), letters, journal entries, and transcribed recordings by a 1) security guard and 2) police officer. Together, these testimonials commingle, asserting diverse truths, facts, perceptions, and stances; collectively, about a dozen narrative points of view draw conclusions that validate disparate choices and actions. Each individual sees their behaviour as ethically correct, but the lack of consensus among the narrators hints at the arbitrariness of value-formation in general. The editor explains, “this book makes no attempt to answer all the questions, lend support to any of the wild hypotheses, prove or disprove any of the unsubstantiated claimed. What it does do is bring together in a single volume, for the first time, the first-hand accounts of the participants in the story.” If nothing else, the sequence of accounts highlights human ingenuity for not getting along, of agreeing to disagree.

*

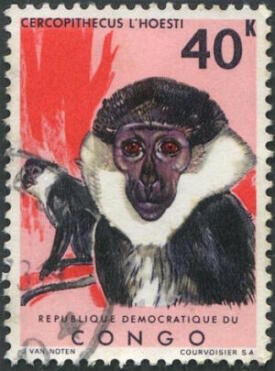

The facts of the matter, in the case of Lucy and Bonbon are clear enough — circa 2002, Ontario resident and grocery store clerk Lucinda Gerson visits her sister Susanne, a primatologist in Africa, and decides — “maybe he’s a little bit sad and a little bit lonely, sort of like me,” the transcription of her journal recounts — that having sex with a bonzee (a fictional chimpanzee related to a bonobo) is a worthwhile pursuit. She returns home to discovery her pregnancy, which results in a child she names Bonbon. The child’s reception, his legal status, his meaning, well, those are as varied as the narrative points of view LePan introduces.

Lucinda, whose transcript pages take up the largest portion of the book (and which abound with ungrammatical constructions — “I’d knowed,” “so’s they” “I didn’t have nothing” and “somewheres else” — but also reveal fluency with Jamaica Kincaid and terms like “ethical questions,” “controlled environment,” and “human exceptionalism”), describes her experiences in Africa, Canada, and the United States, where she’s notorious but also a mother interested above all in the wellbeing of her son. Others, such as Lucinda’s sister and Robert B. Goddard, a director of an esteemed animal research institute, see Lucinda’s actions as immoral (and “disgusting,” in Susanne’s view) and her lack of education and professional experience as sufficient reason for her to lose any claim on her hybrid child. As legal bodies, interested religious parties, and research institutions wrangle over the fate of Bonbon — what environment is best for him, for example, and what species is optimal for his development — Lucinda uses her own wiles to answer the same questions. (Bonbon’s own sentiments, found in a manuscript with suspicious provenance, express heartfelt anguish and longing, albeit with idiosyncratic writing — “Zoo people was say me things over, and was say me things again.”)

The editor’s Preface asks, “has the existence of a hybrid ‘changed everything;’ in terms of how we define what it means to be human and what it means to be an animal?” As Lucy and Bonbon races toward a conclusion, with mother and son on the run and desperate for safe territory, LePan emphasizes narrative propulsion somewhat at the expense of the “novel of ideas’ and “self-reflexive fiction” components of his book. In regard to the editor’s question, Lucy and Bonbon scratches the surface. Based on the spectacle Bonbon represents in the world of the novel and the media sensation his very existence generates, nothing much changes. In the novel, Lucinda and Bonbon’s story is a sensation, a blip in the news cycle — it generates clicks and jokes and uproar but apparently no deep thought, no sea-change. As for “what it means to be human and what it means to be an animal,” those remain the same more or less from beginning to end. The outside world, in LePan’s novel, isn’t ready yet to take questions of that nature seriously.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, published in 2021 with Now or Never Publishing, was reviewed here by Geoffrey Morrison. A previous book, Oldness; or, the Last-Ditch Efforts of Marcus O (2018), was reviewed by Dustin Cole. Editor’s note: Brett Josef Grubisic has recently reviewed books by Paul Headrick, Christopher Evans, Brad Fraser, Robert James O’Brien, Kevin Holowack, Sarah Mintz, and Cedar Bowers for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

12 comments on “1454 Clicks and jokes and uproar”