1447 Memoirs, scripts, subtexts

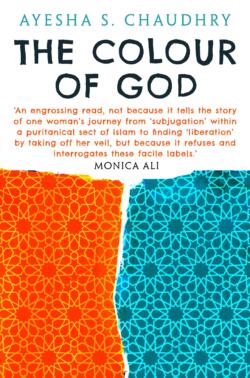

The Colour of God

by Ayesha S. Chaudhry

Toronto: Simon and Schuster Canada (Oneworld Publications), 2021

$30.00 / 9781786079251

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

Note: Ayesha Chaudhry’s The Colour of God was previously reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

I know a journalist who balks at the word memoir. Though it would be easy to cynically quip about the state of journalism and the hilarious pathos of a journalist finding fault with a genre of writing—an unwarranted elitism given that, you know, they are a journalist—it is worth pointing out that Ayesha S. Chaudhry shares this journalist’s distaste for the word memoir; or, at least, she did in an Instagram interview. And I think it’s for the same reason that some people with feminist principles don’t care for the word feminism. It’s become tainted with bad associations. Memoir is feminine, crude, and needlessly self-indulgent; memoir is failed autofiction. Memoir is a diary from a sixteen-year-old girl. The problem with these flawed associations of memoir, though, is that we are forgetting something crucial: we are all sixteen-year-old girls, and some diaries—memoirs—are better than others.

I know a journalist who balks at the word memoir. Though it would be easy to cynically quip about the state of journalism and the hilarious pathos of a journalist finding fault with a genre of writing—an unwarranted elitism given that, you know, they are a journalist—it is worth pointing out that Ayesha S. Chaudhry shares this journalist’s distaste for the word memoir; or, at least, she did in an Instagram interview. And I think it’s for the same reason that some people with feminist principles don’t care for the word feminism. It’s become tainted with bad associations. Memoir is feminine, crude, and needlessly self-indulgent; memoir is failed autofiction. Memoir is a diary from a sixteen-year-old girl. The problem with these flawed associations of memoir, though, is that we are forgetting something crucial: we are all sixteen-year-old girls, and some diaries—memoirs—are better than others.

Previously, Chaudhry authored a textbook. The Colour of God, which I will, in deference to Chaudhry, refer to as amazingly compelling nonfiction rather than memoir (but it is a memoir), is, mercifully, not a textbook. It is, though, educational, often humorous, and accessibly conversational. I’m biased, having previously written to Chaudhry for Toronto café recommendations, but while reading The Colour of God, I felt like we were in conversation. That I was a rapt audience member, and my questions were probably going to be answered.

The limitations of a single book or a single person somehow becoming unequivocally representative—a phenomenon that is much, much more likely to happen with a nonwhite author, mind you—cannot be understated. I am, however, comfortable acknowledging how much I learned about my own ignorance when it comes to Islam. It’s easy to see a woman covering her hair and from Western principles deduce oppression wholly antithetical to an elementary idea of feminism. But, Occam’s razor notwithstanding, the simplest explanation is, in fact, often wrong.

Chaudhry is good at exemplifying what it feels like to be the person with The Answers: “I became good at answering the questions, they were so frequent, so predictable, so … boring. … I was so much more than the hijab. I had ideas about things. But most people couldn’t get past the fabric on my head to hear me. … I’d answer patiently, calmly, mindlessly. Other times, my answers were testy, frustrated, annoyed. … And then in my head, This is what a Canadian looks like, motherfuckers” (p. 38). Has anyone put that on a T-shirt yet?

I cannot confess that I know how Chaudhry’s mind works. For one, I don’t even know how my own does. When I met Chaudhry, I worked in a bookstore. She asked me for a specific title and, if memory serves, walked out with James Baldwin, Cathy Park Hong, Claudia Rankine, and specially requested Monica Ali and Bhanu Kapil. Though some silly gospel will suggest you cannot judge a book by a cover, I think you certainly can judge people by what they read (mind you, I don’t mean ‘judge’ in a judgemental way. Stay with me here) and I understood that Chaudhry either was very invested in race relations, or invested in the appearance of such. Since the latter was patently ridiculous, the former made much more sense. She even lent me her copy of The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers. More than once, I thought: can I be you when I grow up?

But let’s go back to when I first met Chaudhry. She was asking about a specific title, as I said. And when I told her that it was coming out in May and that there were already nine pre-orders, she started laughing exultantly — the book she was inquiring about was her own. I found this utterly charming. I could say it was childlike, but that would suggest that unbridled enthusiasm belongs only to children, and I don’t believe that; Chaudhry is proof. In another encounter, Chaudhry signed my copy of her book and made a point to tell me that she looked at all the places where I had put Post-its. I would have done the same thing, but with much less charm.

In the following passage, Chaudhry gives us a sliver of how her brilliant, often hilarious mind works: “Whenever I hear about incredible, selfless people who devote their lives to the services of others, who sacrifice their own needs so they may help others in need, I wonder about the ways they fail their own families to be these people” (p. 52). In other words, Chaudhry is no superficial thinker. There is often an unaddressed dark underbelly to things.

There is no Sheryl Sandberg moment, and thank fucking God for that. For all her voluble scholastic credentials, Chaudhry writes that “I wish I could end by saying that I’m done feeling guilty about talking to much. That, Damn it, I talk too much and the world is better off for it! … I’m smarter about talking now…. In social settings, I regularly check in with myself to see if the men and white people do most of the talking. When I speak—especially if I express an opinion—they look at me, suddenly aware of my presence, like they are seeing me for the first time; they might smile or purse their lips as they say, You are just too much! Which, of course, is another way of saying, not enough” (p. 80). Chaudhry has a knack for subtext. She never descends to self-pity, which, for creative nonfiction, is exceedingly difficult. When she writes, she is just telling you how things are, how they ought to be, and how they still aren’t what they ought to be.

Chaudhry’s self-censure reminds me of The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson, who writes:

… being someone who spoke freely, copiously, and passionately in high school, then arriving in college and realizing I was in danger of becoming one of those people who makes everyone else roll their eyes: there she goes again. It took some time and trouble, really, but eventually I learned to stop talking, to be (impersonate, really) an observer. This impersonation led me to write an enormous amount in the margins of my notebooks—marginalia I would later mine to make poems. Forcing myself to shut up, pouring language onto paper instead: this became a habit. But now I’ve returned to copious speaking as well, in the from of teaching.

Sometimes, when I’m teaching, when I interject a comment without anyone calling on me, without caring that I just spoke a moment before, or when I interrupt someone to redirect the conversation away from an eddy I personally find fruitless, I feel high on the knowledge that I can talk as much as I want to, as quickly as I want to, in any direction that I want to, without anyone overtly rolling her eyes at me or suggesting I go to speech therapy. I’m not saying this is good pedagogy. I am saying that its pleasures are deep (Nelson, pp. 47-48).

In that passage, Nelson makes a case for being comfortable with expressing yourself in more than one medium. If you don’t want to be an opinionated in public, particularly as a woman, you can still write in the margins. But, importantly, not everyone who becomes silenced becomes a renowned author/poet/memoirist/professor; I daresay, most people who are silenced do not experience Nelson’s literary success. Interestingly, gender is not overtly explicit in Nelson’s self-censure. The omission is curious.

The Colour of God is not rife with convenient solutions for sexism, racism, or troublesome beauty standards. The subject matter won’t allow for that. Instead, you get to ruminate. Chaudhry acknowledges that sometimes personal storytelling means simultaneously living up to and subverting stereotypes. It reminds me of how, as a child, I took piano lessons. Given my Chinese descent, it’s not difficult to imagine how, perhaps, I was tortured into these piano lessons, prodded into becoming a prodigy; maybe parental violence was involved. And what if that were true? When you fulfill a stereotype, either partially or entirely, does that make you less of a person? And if that were false, would that somehow be a plot twist to limited ideas of Chinese parenting?

And so, when Chaudhry writes that —

I realised … how my wearing niqab in Canada … was never about Islam alone. It was also about individualism, and agency, and control over my body. Those ideas that white men came up with for themselves, during what they call the ‘Enlightenment’, when they thought that women were less human than men and that white people were the human-est of them all. Sometimes we think we’re being really clever and original in breaking a standard, boring script only to realise that we’ve fallen into another one without even knowing it. We can’t actually write our own scripts, I think. Scripts are huge, they’re bigger than any of us, they’re formed by societies and cultures and religions over time (p. 126).

— Damn it, Chaudhry. I was really hoping we could write our own scripts.

One of my favourite points in The Colour of God is Chaudhry’s point about the word ‘extremism’ and, concomitantly, ‘extreme.’ You could say it’s nearly impossible to communicate without resorting to hyperbole, but, then, you would be hyperbolic. In the same way that being ‘fine’ now provokes concern, ‘extreme’ has supplanted ‘very’ and ‘so.’

Chaudhry writes: “Extremism is one of those words that does a lot of work but is somehow empty of meaning. It is a word that is heavy with moral censure, easily manipulated by opportunistic politics. It is a word that is necessarily vague and hazy; in order for it to have endlessly varied uses, it must resist a fixed meaning.” I think non-academic books by academics often excel in judicious uses of semicolons and The Colour of God, by the way, is no exception. Anyway, to continue quoting Chaudhry: “So its meaning is always fluid and subjective, and the way it is used gives us insight into what its user perceives as dangerous or threatening to their own interest. Whenever I hear the word ‘extreme’ or ‘extremist’ used to describe an idea or a person, I wonder, What work is this word doing for you? How are you positioned, in relation to this extremism? How do you benefit from the demonization of this person, group or idea?” (p. 145). In other words, pay attention to how a person uses the word “extreme” and all its variegations. It says more about them, than whatever they are denoting as extreme.

Chaudhry writes convincingly on many topics, ranging from permanent hair removal; Eurocentric beauty standards (Chaudhry wanted to be like Anne of Green Gables. I bet Anne, given that she loathed her red hair and freckles, would be incredibly flattered); baldness; vasectomies; not having children; and how, rather depressingly, knowing better does not mean doing better. I mean, really, if I had to describe the serious pitfalls of humanity with one sentiment, it would probably be that.

I have long had difficulty understanding why anyone would, of their own volition, intentionally, deliberately, premeditatedly, have a child (let alone children, plural). I’ve come to the unsatisfying conclusion that, much like parents who can’t conceive of not being a parent, it’s simply a phenomenon I won’t understand. Still, though, I try to understand. It was, in fact, my biggest frustration with Nelson’s The Argonauts. Am I simply supposed to accept intrinsic desire as a sufficient reason to use the bulk of a prestigious, lavish Guggenheim fellowship for a child? Doesn’t wanting to have a child, nine times out of ten, generally mean wanting to have a child that is biologically related? The narcissism! Or, if you prefer, the biological imperative that, apparently, cannot be outsmarted. I’m not one of those people who ingratiatingly (or sincerely) say, “I love children, but.” There is no but. I do not love children, which, by the way, was true when I was a child. Maybe, though, my self-esteem is too low to believe that passing on my genetics would actually be the least bit beneficial to me, or the world. Mind you, I don’t actually believe this, but I thought having one self-deprecating comment might rescue me from the fate of rude e-mails about my reproductive system.

I have long had difficulty understanding why anyone would, of their own volition, intentionally, deliberately, premeditatedly, have a child (let alone children, plural). I’ve come to the unsatisfying conclusion that, much like parents who can’t conceive of not being a parent, it’s simply a phenomenon I won’t understand. Still, though, I try to understand. It was, in fact, my biggest frustration with Nelson’s The Argonauts. Am I simply supposed to accept intrinsic desire as a sufficient reason to use the bulk of a prestigious, lavish Guggenheim fellowship for a child? Doesn’t wanting to have a child, nine times out of ten, generally mean wanting to have a child that is biologically related? The narcissism! Or, if you prefer, the biological imperative that, apparently, cannot be outsmarted. I’m not one of those people who ingratiatingly (or sincerely) say, “I love children, but.” There is no but. I do not love children, which, by the way, was true when I was a child. Maybe, though, my self-esteem is too low to believe that passing on my genetics would actually be the least bit beneficial to me, or the world. Mind you, I don’t actually believe this, but I thought having one self-deprecating comment might rescue me from the fate of rude e-mails about my reproductive system.

As a result, I am often ebulliently overjoyed when someone is able to write about being voluntarily childless in a, shall I say, less polarizing way than I just did above. Chaudhry, being perhaps considerably more emotionally generous than I am, writes “If I wanted children is reason enough, then I didn’t want them should be reason enough, too.” Nothing overwrought or pathologically intellectual. Just a good dose of pith. And so, perhaps, understanding why people would want to have children — and vice versa — is beside the point. Different people want different things for different reasons. Maybe Occam’s razor has a place in the world, occasionally.

Categorizing this book in a more specific subgenre of memoir — I’ll leave this pursuit for Linnaean booksellers. After all, as Chaudhry writes, “Humans, by their very definition, are leaky.” This book bleeds and oozes. It’s the best pus that prose could have, really.

*

Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and a pianist of dubious merit living in Toronto. She is currently an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has recently reviewed books by Gillian Wigmore, Meichi Ng, Alex Leslie, Zsuzsi Gartner, Robyn Harding, Brad Hill & Chris Dagenais,and Lindsay Wong.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

9 comments on “1447 Memoirs, scripts, subtexts”