1438 Bill Holm (1925-2020)

Bill Holm (1925-2020)

An obituary by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

*

Think of a slow, gentle, deep-water earthquake. You may have missed it, but think how its waves reverberate for a long long time, repeatedly coming ashore and changing entire landscapes over time.

That was American art historian Bill Holm.

Bill Holm died in December 2020 at the age of 95. In the 1950s and 1960s he had much contact with Wilson Duff at the Provincial Museum of British Columbia and at UBC — the topic of a forthcoming book by Robin Fisher, Wilson Duff: Coming Back, a Life (Harbour Publishing, 2022).

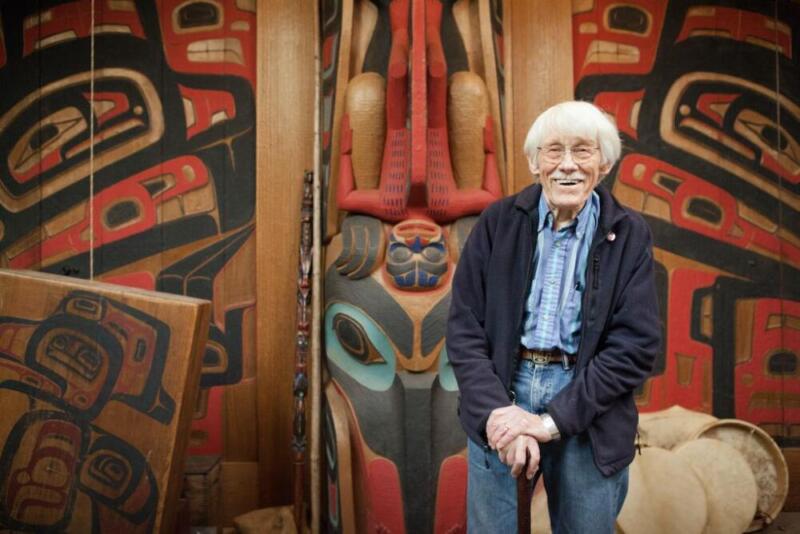

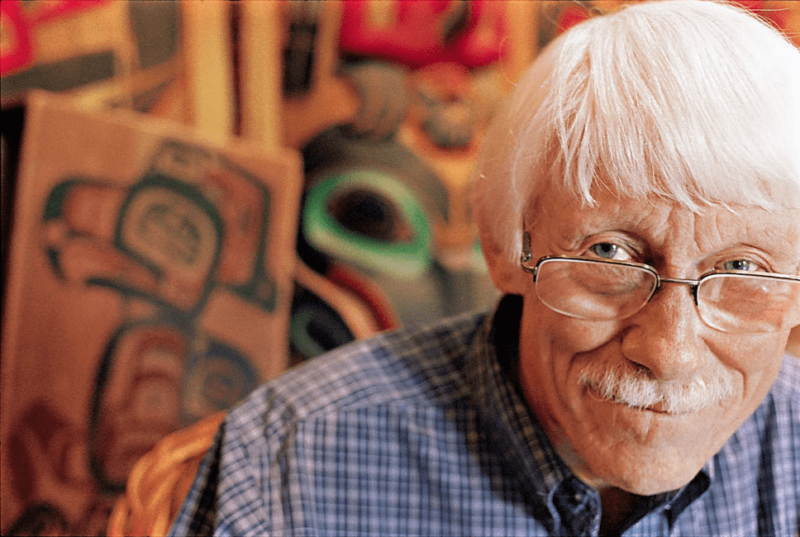

Holm’s death was announced by his family: “Ninety-five years of boundless curiosity, of limitless sharing of skills and knowledge, of earnest creating of connections across generations, across cultures, is the cherished legacy we have all received from him.”

You may not know who he is, but you have probably seen his influence in the artwork of many Indigenous artists. You may have seen Indigenous exhibits organized by museum curators he coached, or read books by researchers he mentored; and you may have been exposed to Indigenous culture through the thousands of enthralled students he inspired. You may even have seen one of his own paintings or drawings, or read an article or a book or two that he wrote.

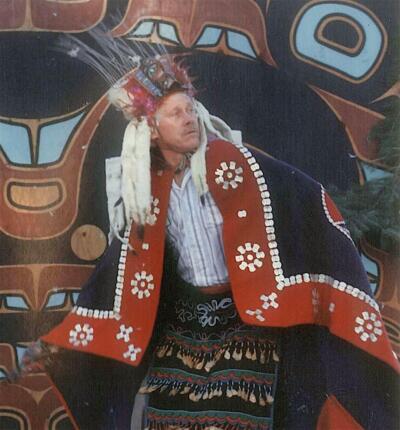

Holm did not have Indigenous ancestry, but Indigenous art was his passion as an artist and as a teacher. His analysis of Northwest Coast native art was ground-breaking.

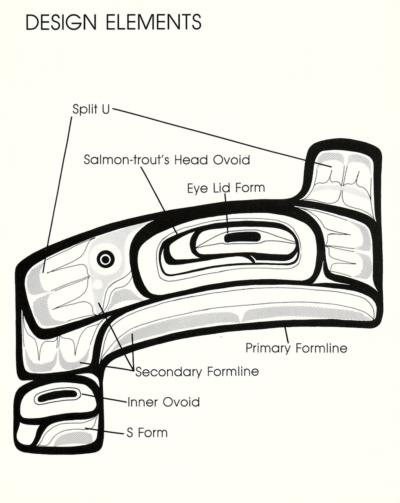

A paper he wrote in 1958 for a class taught by Dr. Erna Guenther, Curator at the Burke Museum in Seattle, became the seed for his book Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form. First published over 50 years ago, it is still in print and still selling, having become one of the all-time best-selling books at the University of Washington Press and sold more than 120,000 copies. It made his reputation as one of the most knowledgeable experts in the field of Northwest Coast Native art history. It also created a language, a visual grammar, to look at the art and identify stylistic elements within it to describe the art (examples include “formline,” the “ovoid,” the U and the split U). His book examines those elements and the use of colour (e.g., black is used for the primary formlines; red is for secondary formlines and details). Almost every page includes his drawings or photographs that demonstrate the artistic principles. Northwest Coast Indian Art helped define the field. This classic analysis will change the way you see this art.

Holm received his Master’s in Fine Arts in painting from the University of Washington in 1951. He returned for two teaching certificates while teaching at Lincoln High School, Seattle, for fifteen years before being recruited by the University of Washington for two interrelated jobs: lecturer at the university, where his classes on Northwest Coast art were so popular they had to find a room large enough to hold 250 students; and curator at the Burke Museum on the grounds of the university, a post he held until his retirement in 1985.

In the 1940s and into the 50s he spent his summers working as a camp counsellor in the San Juan Islands where he met and married Marty (Martha Mueller), a fellow counsellor. While there he built a replica bighouse where, eventually, hundreds of Kwakwaka’wakw people came every summer to sing and dance. A few years ago, I paddled in an ocean-going canoe with First Nations on Tribal Journeys through the San Juan Islands when someone pointed out the summer camp. I thought it strange that a summer camp would be remarked on — but First Nations from the Canadian side of the border never forgot the camp and the knowledge Bill Holm and his Indigenous friends shared there.

Holm befriended Indigenous leaders and artists up and down the coast, learning Chinook and Kwakʼwala languages, songs, and ceremonies. Two years after the 1883 potlatch ban was dropped in 1951, Mungo Martin, a Kwagu’ł carver from Tsax̱is (Fort Rupert), and carver-in-residence at the Royal BC Museum, held the first legal potlatch for the opening of the ceremonial bighouse, named Wawaditɬa, on the museum grounds. Wilson Duff, ethnology curator of the museum, invited Bill and Marty Holm to attend. They became life-long friends with Mungo Martin and later his grandson, Kwagu’l artist Calvin Hunt. A few years later, in 1959 at a potlatch, Holm received the hereditary Kwakwala names Ho’miskanis and Tɬalelitɬa, making him a member of the community.

Nuu-chah-nulth artist Joe David, a long-time friend, is quoted as saying, “I am lucky to have lived in the time of Bill Holm.”

Another example of the warm respect Indigenous leaders and artists have shown him is that Holm was the only non-Native person to receive one of the twenty-five coppers gifted to honoured invited chiefs at the installation of Guujaaw, the Haida Chief.

Bill Holm was fully aware of the tension between a respect for Indigenous culture and issues of appropriation. Although he carved, drew, and painted in Indigenous styles, he did so to learn them, and he never sold those works. He approached his passion from an art historian’s perspective, fully conscious that while the knowledge was not his, it was his responsibility to share that knowledge. He did so with every article and book he wrote.

To start to get to know Bill Holm, read Steven Brown ’s book Sun Dogs and Eagle Down: The Indian Paintings of Bill Holm (out-of-print but still available). It is richly illustrated with Holm’s own paintings and drawings and weaves together with his work as an artist, his scholarly art historical analysis, and his work as a curator of Northwest Coast Indigenous art. It is also revealingly sprinkled with Brown’s warm reminiscences. “The uniqueness of Holm’s relationship to his work shines through,” writes Brown, “providing an experience for the viewer that is carefully conceived, honed with familiarity and accuracy, and polished with his love of light, colour, and form.” That also describes Bill Holm himself: a unique individual, thoughtful, knowledgeable, and quietly accurate. Everything he did was done lovingly and well-imbued with light and colour.

In the era before the Internet, Holm received a national fellowship to travel Europe and North America to examine and photograph Northwest Coast objects, many of which were not known to others or understood by the museums holding them. His immense 30,000 slide collection became a resource magnet (and the stuff of a legend) for artists, scholars, students, and museum staff. He shared freely and his slides were often used to illustrate books. There is even a publication about his collection.

In the era before the Internet, Holm received a national fellowship to travel Europe and North America to examine and photograph Northwest Coast objects, many of which were not known to others or understood by the museums holding them. His immense 30,000 slide collection became a resource magnet (and the stuff of a legend) for artists, scholars, students, and museum staff. He shared freely and his slides were often used to illustrate books. There is even a publication about his collection.

While Holm’s first book, Northwest-Coast Indian Art, was intended for art historians, it is also considered the preeminent authority amongst carvers. He inspired three books which acquired a similar status for weavers from Alaska down the BC coast and through Puget Sound. Paula Gustafson credits Holm’s collection of slides that illustrate many of the Salish blankets in her book Salish Weaving (Douglas & McIntyre, 1980), which every Coast Salish weaver keeps close by. It covers the known history of Coast Salish blankets, the fibres used, the spinning methods, tools, dyes and weavers.

The Chilkat Dancing Blanket and The Raven’s Tail, both written by Cheryl Samuel, analyze and demystify two other important weaving techniques — raven’s tail and Chilkat (Naaxiin in Haida) techniques, the weaving styles of the northern nations (Tsimshian, Tlingit, Chilkat, Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw). Samuel expressed her gratitude for Holm. “Where would we be,” she writes, “without the knowledge, enthusiasm, and generosity of Bill Holm? What would our work be without the standards he sets for himself and inspires in us?”

Holm was born in Roundup, Montana, March 24, 1925 and moved to Seattle with his family aged 11. A year later, his mother took him to the Burke Museum to help assuage his curiosity for Native American culture. His heart and soul never really left the museum. It is still there.

Sixty-five years later, in 2003, the Burke Museum created the Center for the Study of Northwest Native Art and named it after him. Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, curator of Northwest Native Art at the Burke and director of the Bill Holm Center, is committed to carrying on his legacy. “His spirit of teaching anyone who came to learn imbued the Burke in the tradition it carries on today,” she remarks.

In 2020, shortly before Bill Holm passed away, the Burke Museum produced a powerful short video to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Bill Holm’s 1965 book “Northwest Coast Indian Art: An Analysis of Form which can be viewed here.

The University of Washington Press even has a book series named for him — Native Art of the Pacific Northwest: A Bill Holm Center Series. The series includes Return to the Land of the Head Hunters, to mark the centenary of Edward Curtis’s 1914 silent film In the Land of the Head Hunters. With a foreword by Bill Holm, the book is enhanced by Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw perspectives to bring together thoughts on Curtis, early photographers and “the vanishing Indians” myth, and the input of scholars, historians, artists, and Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw collaborators in a wide-ranging discussion about the film, as well as its historical context, photographer Curtis as a musical ethnographer, and the reconstruction (rather than restoration) of the making of the film.

Other books in the series include Unsettling Native Art Histories on the Northwest Coast, edited by Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse and Aldona Jonaitis and reviewed in The British Columbia Review here, and most recently Painful Beauty – Tlingit Women, Beadwork, and the Art of Resilience.

Brown, in his preface to Sun Dogs & Eagle Down, likens Holm to the Pacific Ocean: “To attempt to do a book on Bill Holm, or even on a single facet of his multiple talented personality, is like doing a book on the Pacific Ocean – it just keeps getting deeper!” And like an underwater earthquake, Holm shook the waters and started the waves of energy that have fuelled books about, and research into, the practices of Northwest Coast Art. And these just keep coming, wave after wave.

*

Retired from Vancouver Island University where she held the position of Director of Research Services, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa now spends much of her time studying Coast Salish textiles. She holds an MA in Educational Technology and a Master Spinner’s Certificate. She has worked with museums in North America and the UK including the Smithsonian, the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum, the RBCM, the Museum of Anthropology at UBC, and the Burke Museum in helping to identify yarns, fibres, tools, and techniques used to create the yarns. She was instrumental in identifying a rare blanket in the Burke Museum as being made of woolly dog hair. She has given many presentations and workshops on Coast Salish spinning and textiles and has written articles on the subject for magazines such as Selvedge, Spin-Off, and Ply — and for BC Studies on the use of diatomaceous earth in Coast Salish blankets. She lives on Protection Island, in Snuneymuxw territory. Editor’s note: Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa has also reviewed books by Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse & Aldona Jonaitis and Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, & Willard Joseph for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

12 comments on “1438 Bill Holm (1925-2020)”

What a wonderful view! A fine portrait of an inspiring man. Thanks for this.

Bravo Sis. Written with love and precision.

Thank you, Liz, for this beautiful and informative tribute to our late Dad. ❤️ May his spirit continue to support and inspire you and all who travel toward cultural understanding, openness, and the generous gifts our hands learn to create.

Thank you Carla. It was a pleasure to do this! As Joe David said “I am lucky to have lived in the time of Bill Holm.” We are all so lucky!

Liz HK

Same here!

I still have his book on the Analysis of Form, on the reading list of my Museum course at MoA, for my BA in anthro, in the early eighties.

Such amazing life-long dedication on Bill Holm’s part to the understanding and promotion of First Nations’ visual culture.

I too have my precious Analysis of Form from the early 70s or 80s. Despite being an uninformed student who moved every year, who lost or left behind possessions, I held on to this treasure. I hope it is still on reading lists.

Liz HK

A great tribute to a remarkable human being. Bill Holm was my introduction to colour, line and form — Northwest Coast style.

Thank you, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa.

Thank Bill Holm for inspiring us. And thank YOU, Michael, it is a good feeling to see a writer appreciate this.

Liz