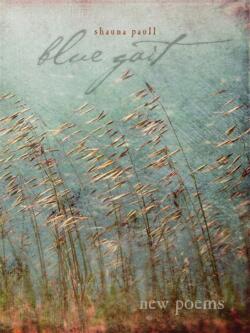

1407 Soft bells of beauty and blue

blue gait

by Shauna Paull

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2021

$19.95 / 9781896949888

Reviewed by Yvonne Blomer

*

Another word for gait is stride or way of walking, and Shauna Paull’s new poetry collection blue gait parallels the ways of walking through and on the land, with the natural world, beauty, women, and Indigenous people in mind. Her poems create parallels or contrasts between beauty: a “hummingbird a stellar’s jay” and violence: “even though our mines and pipelines clear-cuts and dams/… a woman sends a poem about male violence/ love poems to the face of it.” These poems are rich in empathy, not apathy, and rich in action: in the strength of being and of writing in this world.

Another word for gait is stride or way of walking, and Shauna Paull’s new poetry collection blue gait parallels the ways of walking through and on the land, with the natural world, beauty, women, and Indigenous people in mind. Her poems create parallels or contrasts between beauty: a “hummingbird a stellar’s jay” and violence: “even though our mines and pipelines clear-cuts and dams/… a woman sends a poem about male violence/ love poems to the face of it.” These poems are rich in empathy, not apathy, and rich in action: in the strength of being and of writing in this world.

blue gait is a book of untitled poems with small drawings of birds to mark the start of each poem. Because Paull eschews titles, the collection almost reads as a long poem, with illustrated pauses.

The book is beautifully designed. The sketches, font, script, and poems suggest journal entries or letters to loved ones. I would not always notice the small details, but those birds are essential markers to the poems: the quiet determined voice, unpunctuated, of small passerines hopping on the line, creating spaces, forming the very flow of poems and book. blue gait is a finely crafted artifact, both in its poems and in its creation. I wish to praise Mona Fertig and Mother Tongue Publishing for this — Fertig’s last book before the press closes.

If I open to any poem in this collection, such as “the one who plays four late sonaten” (p. 58), what I find is beauty: threads of song leading to grief or astonishment, and a discovery of how we humans interact with and alter the natural world around us. After “I wept,” the music from the human calls in the larger natural world — “then the treble of tumbling water,” and looks at the peril of the human, “the terrible leap of us.” From there, Paull offers a close moment and a parallel, “the sky train home/ a boy in a hoody plays harmonica like percussion,” and then to an intimate image, of a child and her “hair/ tangling in north shore clouds.” The poem ends on “somehow/ our bliss all our harm.”

“the one who plays four late sonaten” beautifully captures the elegance of blue gait, a humanist’s book that sees our infinite links to the natural world and each other but also how we imperil both. It holds praise in one hand, its opposite in the other, and moves between not the abstract notions of grief and hope but their exact and concrete sensory moments. Here we have human-made beauty and desecration as well; innocence and experience, as Blake might have said.

The first section, “carry my hand,” contains love poems to Shauna Paull’s granddaughter, to friends and family, poems of intimacy that contain the natural world with the human body sitting alongside, so that “a scarf the colour of grass spring azure sky/ all the colours of earth day // I knit on my rocker planet spinning / cities’ hearts imploding I knit unquietly with the dead.” All things here and throughout the book are intertwined, knitted, interlaced.

In the second section, “brave as moonlight,” Paull encounters white entitlement and violence to women and land set against a hummingbird, a stellar’s jay, a cooper’s hawk. She allows images to fold over one another and further explores the juxtaposition: nothing is certain but so much goes on at once, both destruction and creation, working together, working against: “but there’s something a humming flung up/ billows out beyond/ the cash-cage…/ its myth of completeness.”

Beyond the spacing of poems on the page, Paull’s use of repetition creates an incantation-like quality, like drumbeats or footfalls, these echoes. In “now is later,” the first line is incanted throughout, “but now is later/ drone strikes beheadings/ raids on unist’ot’en oil spills…/ now is later/ her red slip-rhythmed grace.” Here also the political sits alongside the personal.

In the third and fourth sections, “sky because sky” and “enter the ceremony like water,” we shift into some denser poems that move quickly through spaces and language while maintaining the echoes of repetition and cadence: “all the way all the way around we made it all the way around this lake/ your bell sound hands and the lighting you sometimes wrestle…” Poems here feel not only denser, but fast paced and still flowing.

Here we find ancestors and the colours blue and red, the fear, the strength — blue sky, red dresses. The pace of walking in a neighbourhood and through memories and people captures me in blue gait, how multiple things or moments are noticed at once. In the poem that begins “to enter the ceremony broken,” that phrase leads to “arrive quietly/ lift gently/ your face to what is/ simple,” and then moves to “be unconcerned by the brash rancour of cities/ built over the bodies of these lands…” then “enter the ceremony like water/ arrive quietly/ palms gentled open.”

The final section “oldest portal” contains poems of still rage, still beauty, but also grief travels through. Though I have touched on the sections of blue gait, it holds in its entirety. It is a collection of poems made of multiple soft bells tolling both beauty and ugliness; the good humans do, and the bad; the horrors of settlers’ tenure on Indigenous land but also the friendships and inspirations.

A few favourite lines: “brash rancour of cities,” “my heart is tractored,” “blue swing of an old gate/ gait of slow horses around us” [perhaps the title is in these lines], “red-wild good,” “the wingspread cedar,” “wildfires worry vertebrae,” and “who will do the wide-hipped work of love.”

And when you read these fragments, you know the poems they live in are rich with thesis and antithesis, a pattern that leads to the final poem, “there is death now and now,” which goes: “mother beloved father / and then years near/ years under the blue hum the winged ones know,” and to the second part, “and all the ones whose gifts,” and then to a list of the creatures and humans: “the one who carries her calf for seventeen days,” for example, and “the one whose house is belonging.”

*

Yvonne Blomer (she/her) lives in Victoria on Lək̓ʷəŋən territory. The Last Show on Earth, her fifth book of poetry, was published with Caitlin Press in 2022. She was Victoria’s fourth poet laureate. Editor’s note: Yvonne Blomer has also reviewed books by Elee Kraljii Gardiner and Heidi Greco (editor) for The British Columbia Review, and her edited collections Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds and Refugium: Poems for the Pacific were reviewed by John Swanson and Phyllis Reeve.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1407 Soft bells of beauty and blue”