1406 Trauma, detox, paradox

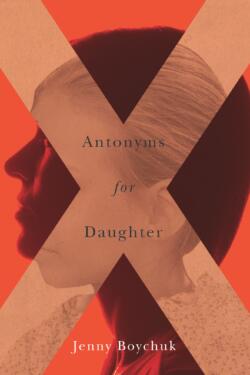

Antonyms for Daughter

by Jenny Boychuk

Montréal: Véhicule Press, 2021

$17.95 / 9781550655810

Reviewed by Jane Frankish

*

This collection of poetry from Jenny Boychuk presents the familiar sentiments of mother and daughter bonding but it also bears traumatic talons which seem to reach in and pierce that bond. I was particularly struck by the title, Antonyms for Daughter. An antonym is a word that has the opposite meaning to another. Boychuk’s use of this term suggests the state of being at odds with something or of not being something, which, in this instance, is a ‘daughter.’ She has used this idea to generate an extended metaphor for her painful and paradoxical relationship with her mother who suffered from a substance abuse problem. In the epigraph, Boychuk uses a quotation from a poem by Adrianne Rich to point to the visceral essence of human existence, an existence made possible by procreation, by the coming together of others in the bringing forth of yet others.

This collection of poetry from Jenny Boychuk presents the familiar sentiments of mother and daughter bonding but it also bears traumatic talons which seem to reach in and pierce that bond. I was particularly struck by the title, Antonyms for Daughter. An antonym is a word that has the opposite meaning to another. Boychuk’s use of this term suggests the state of being at odds with something or of not being something, which, in this instance, is a ‘daughter.’ She has used this idea to generate an extended metaphor for her painful and paradoxical relationship with her mother who suffered from a substance abuse problem. In the epigraph, Boychuk uses a quotation from a poem by Adrianne Rich to point to the visceral essence of human existence, an existence made possible by procreation, by the coming together of others in the bringing forth of yet others.

The poems in this collection seem to emerge from the author’s recognition of her mother as an opposite to herself, an opposite without which she has no existence. As I read Antonyms for Daughter, I felt that the poet’s selfhood had been subsumed by the trauma of this mother/daughter relationship. The child denies itself to survive and the mother, in turn, denies the child, and yet, there persists an unbreakable bond of parent and child. All our cherished expectations of this relationship are denied, and what is left is the raw essence of the bond itself. It is the sense of this bond that haunts the collection.

Interspersed strategically across the collection are several poems that refer to the title of the collection, antonyms for lullaby, mother, inheritance, daughter, heart, time, and funeral. These antonyms propel the reader along a narrative arc of recollections and reflections from the time before, up to and beyond her mother’s passing.

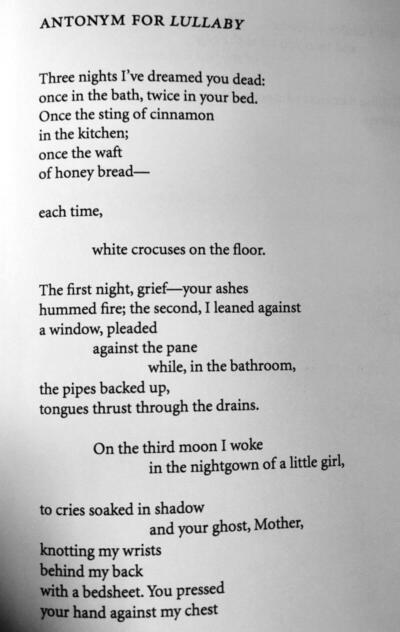

The collection opens with Antonym for Lullaby. A lullaby is supposed to lull, soothe, and relieve distress. I am lulled by the nursery rhythm of Boychuk’s rhyme, but the language here is ominous. An antonym of ‘lull’ is to ‘excite’ and many nursery rhymes have dark undertones. For instance, “Rock a Bye Baby” is said to express a Protestant wish for the death of the infant son of King James II, who was a Catholic.

The collection opens with Antonym for Lullaby. A lullaby is supposed to lull, soothe, and relieve distress. I am lulled by the nursery rhythm of Boychuk’s rhyme, but the language here is ominous. An antonym of ‘lull’ is to ‘excite’ and many nursery rhymes have dark undertones. For instance, “Rock a Bye Baby” is said to express a Protestant wish for the death of the infant son of King James II, who was a Catholic.

Three nights I’ve dreamed you dead:

once in the bath, twice in your bed.

In the next two lines we encounter the ‘sting of cinnamon’ and ‘wafts of honey bread.’ These evocative impressions of being in the mother’s domain, are followed by a violent image of a ghost mother, who is knotting her daughter’s hands behind her back with a bed sheet. The poet addresses this mother:

You pressed

your hand against my chest

until I couldn’t breathe

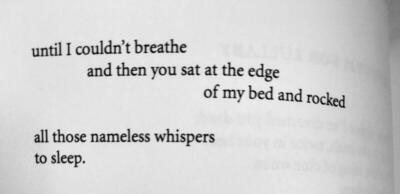

The image becomes soothing again:

and then you sat at the edge

of my bed and rocked

all those nameless whispers

to sleep.

In Antonyms for Mother, the mother is entering detox. The family home is empty. The daughter does not cry with her father. She finds someone to whom she is not a daughter,

In Antonyms for Mother, the mother is entering detox. The family home is empty. The daughter does not cry with her father. She finds someone to whom she is not a daughter,

I find my volleyball coach in the girls’ change room,

cry into her shoulder for the whole next period.

In the last stanza, the mother and child are in the garden. It seems like an idyllic moment: the lilac is out and spring is here. The child cuts a worm in half and is reassured by the mother that everything is fine, that each half will grow back as “with two hearts.” There is a denial of the harsh truth that, at best only one half stands a chance of survival, that the ruptured mother and daughter relationship will never fully regenerate.

In Antonym for Inheritance, there is an internal conflict. The daughter does not want to inherit the mother’s drinking problem but she knows that it is her legacy:

I died to be my mother’s antonym,

but the antonym is never without

When the teenage daughter explores alcohol, instead of having an innocent encounter, she finds her own experience inseparable from repellent images of her mother. She is unable to free herself from the vodka that has become her mother.

Even as the mother fights the vodka, it is the daughter who finds a fist on her cheek. The daughter is overwhelmed by the mother outside, but it is the one within herself, that has caused her individuality to be “submerged.” She will always be her mother’s daughter.

Submerged, the promise

that I would lose her hands forever

In Antonym for Daughter, after which the whole collection is named, Boychuk is pictured clearing out her mother’s wardrobe. As she sorts the clothes, she remembers her mother asking:

Do you still

have that funny little birthmark

on your breast?

The daughter was not ready to speak about her new breasts that now connect her to the mother in womanhood. The memory is a familiar mother/ daughter moment recalled in grief, but in this daughter’s remembrance, there is the added pain of knowing that the mother had always been lost to alcohol.

Antonym for Heart is a sparsely worded poem that exemplifies how emotions become words on the page. It points to the limitation of the meaning of the words themselves. The space between the lines and the asterisk speaks to silence. Boychuk uses an asterisk to show the reader that something is missing, unsayable, unknowable … and this leaves the reader wondering, what is left after death is just a marker for absence, there may be no antonym for heart, just an omission, a blank or gap.

Antonym for Heart is a sparsely worded poem that exemplifies how emotions become words on the page. It points to the limitation of the meaning of the words themselves. The space between the lines and the asterisk speaks to silence. Boychuk uses an asterisk to show the reader that something is missing, unsayable, unknowable … and this leaves the reader wondering, what is left after death is just a marker for absence, there may be no antonym for heart, just an omission, a blank or gap.

Stone. Of course, stone.

*

The opposite of red.

Not black or grey or yellow, but green.

No more beating heart, the mother is no more, her heart is cold, and she lies beneath a stone marker, beneath the grass. The green of the grass is heightened by being cast as the preferred or correct antonym of red. The last line reads like an ending,

Nothing more.

Having laid her mother to rest, Boychuk now seems to begin again, pointing this time towards the eternal. Antonyms for Time is nine stanzas long. It presents the daughter descending with the dead mother into the humours of the earth. The mother is heavy, she is sinking down,

The blue whale sinks,

beneath every layer of earth,

silt and clay.

Everything is whirling and churning, memories of being eight, a star dying, a photo in a drawer, a resemblance, darkness. The poet’s thoughts are swirling capturing images of minute detail and grandiose design, opposites are let loose, the sense of time is abandoned. The ghost of grandma baking bread conjures an aroma, but the dough won’t rise. Instead, the grandmother’s “Guilt swells.” Yet, “somewhere,” far away, there is a place of no ebb or flow, where rising and falling are the same movement,

and like this

the blue whales fall

and rise, and rise, and rise.

Antonym for Funeral is made of broken lines, and it seems to me that it is in these breaks that the poet locates the absence of her departed mother. The daughter has something to say, something that can’t properly be said in words. She reaches back to bring forward fragments of a traumatic relationship, a relationship, nonetheless:

I search for you

in the churchyard

a fistful of baby teeth

to sacrifice

What does it mean to grieve at a mother’s funeral, when you have always grieved the loss of that mother?

you slipped out

of your own funeral

I skipped it too

searched for you

in these living woods

Just as she was in life, the mother remains elusive in death. There is no reckoning, no forgiveness, no understanding for the child who has lost her “baby teeth,” and is now an adult. There is a strange limbo for daughter and mother, who are eternally “knotted” together, yet strangely unable to find each other. They remain lost together.

*

Jane Frankish is a writer of poetry and prose. She is a Master’s student in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at Simon Fraser University and works as a librarian at Vancouver Public Library. Editor’s note: Jane Frankish has written a memoir, Chennai, a place in between, and contributed to Letters from the Pandemic, both for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1406 Trauma, detox, paradox”