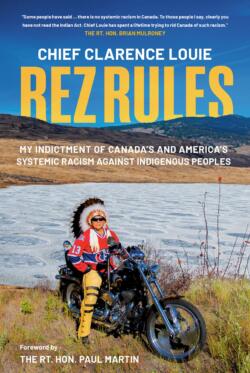

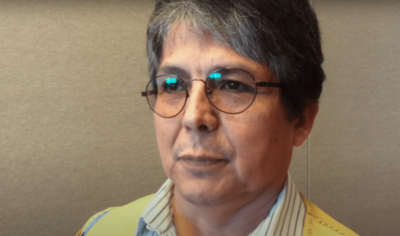

1374 Chief Clarence Louie of Osoyoos

Rez Rules: My Indictment of Canada’s and America’s Systemic Racism Against Indigenous Peoples

by Chief Clarence Louie, with a foreword by Paul Martin

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (McClelland & Stewart), 2021

$34.95 / 9780771048333

Reviewed by Ken Favrholdt

*

When I first met Chief Clarence Louie at the Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) office in spring 2021, I was taken by surprise. He seemed abrupt and disinterested in me. “I only have twenty minutes”, he told me. I wanted to meet him as I was working on a commemorative book for Oliver’s 100th anniversary and the 10,000 years of the syilx Okanagan people’s history.

When I first met Chief Clarence Louie at the Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) office in spring 2021, I was taken by surprise. He seemed abrupt and disinterested in me. “I only have twenty minutes”, he told me. I wanted to meet him as I was working on a commemorative book for Oliver’s 100th anniversary and the 10,000 years of the syilx Okanagan people’s history.

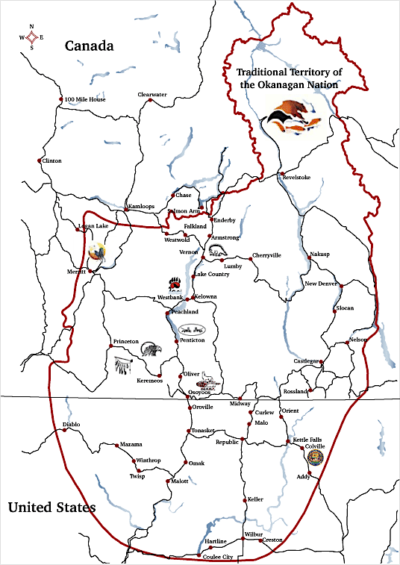

When Louie found out my interest in history, the conversation got interesting and he said we should meet again another time for a couple of hours. We did and we have had several meetings since, discussing the history of the OIB reserve and the impact of colonialism. The Canada-US border split the Okanagan Nation.

I discovered Louie’s passion for history as well. “How can we be sure about what we know?” was an important question Clarence asked me. I have since warmed up to Chief Louie and his way of looking at the world.

When Chief Louie’s book appeared on the store shelves I immediately had to have a copy to find out more about how Clarence viewed the world. I thought I knew a lot about native culture but Louie’s book is an eye-opener and focuses on his own experiences and that of his reserve. It is a personal view of the life he has had from growing up with a single mom to his love for his own family. Now in his early 60s, Louie has had a remarkable career as chief of OIB for over 36 years.

Louie’s book is an autobiography but written in a thematic way. Each of the 20 chapters over 326 pages dwells on a different theme with a connecting thread throughout. There’s a section of colour photographs that give flavour to the narrative. Louie admits he had help writing the book from journalist Roy McGregor, with editing help from McClelland and Stewart’s Jenny Bradshaw. But the strong words and opinions belong to Louie who is unabashed in what he has to say. He admits he is not politically correct and unafraid to “tell it like it is.” But don’t expect an academic indictment of the subtitle the book.

The book begins with an Introduction by the Right Honourable Paul Martin who Chief Louie says is “the only top-ranked elected leader in Canada who truly put their words into action when it came to developing a real ‘nation to nation’ relationship with First Nations” – the Kelowna Accord in 2005 – based on Native organizations setting the agenda. Unfortunately, it died with the election of the Conservatives and Stephen Harper.

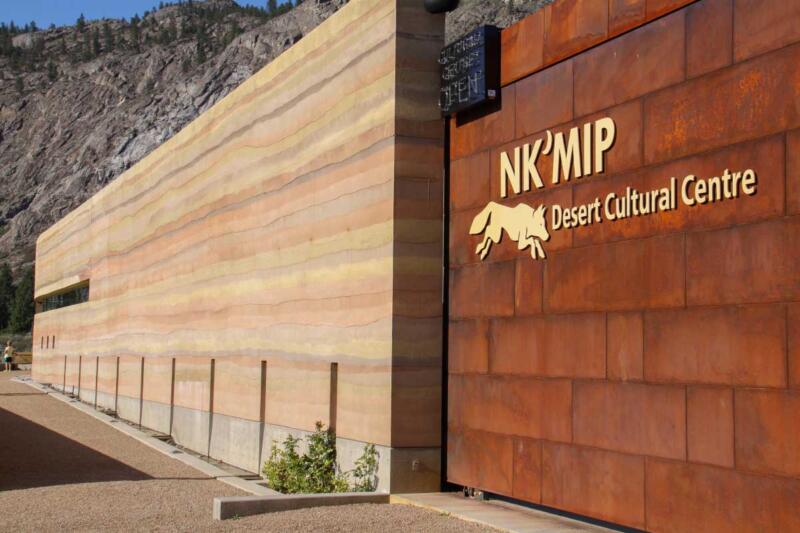

His journey starts in the 1970s when he was sixteen and bought his first vehicle, not a “Rez bomb” as the beat-up cars on the Reserve were called, but a 1968 Ford pick-up. He left the Rez for a summer job with Parks Canada in Kootenay National Park. He had worked before on the Rez at the Inkameep Vineyard which has turned into a major source of revenue for the Band over the years, now Nk’Mip Cellars.

Chapter 1, “Indian Magic”, appropriately begins with the story of his youth on the reserve – the Osoyoos Indian Band. OIB belongs to a tribal council group of the same language-speaking bands on the Canadian side of the border. By Indian Magic he is referring to unintended consequences or karma. He realizes that the reservation system has actually helped to protect Native identity. “Indian Magic turned the Rez system into something opposite of what was intended.” Indian Magic” – “ how some things happen out of the blue and don’t make any sense but make you wonder in amazement.”

In Chapter 2 he describes what he means by Rez Rules that he learned from his summer jobs and involvement in sports. Staying in school is rule number one. And Clarence proved the value of doing that. Louie left the Rez at nineteen and attended the University of Regina in the Native Studies (now Indigenous Studies) Program. He fell in love with the large collection of books on Native history. He then transferred to the University of Lethbridge. His three “happy places” Louie states were the Native Studies classes, the gym where he worked out, and the library. Today he has his own “prized book collection.”

Clarence then entered the Native American Studies program at Lethbridge in the 1980s. He loved reading, especially the history of Indigenous peoples. Louie also likes to quote his favourite heroes, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Chief Joseph. Louie’s first involvement native activism was in 1980 while at university when “young guys” in their twenties from the Blood Tribe organized a run from Blackfoot Crossing to Ottawa. The relay run, transporting a treaty bundle, was a political demonstration about broken treaties. Known as “The Run,” it was also a spiritual event, Louie’s “first great cultural experience.”

When he was first elected chief at the age of 24 in 1984 he purchased his first motorcycle and later found out about the Wounded Knee Memorial Motorcycle Run, an honour ride to South Dakota he has attended since 2009.

Chapter 3 is about Rez Lingo, explaining what it means to be an Elder, a Warrior, and what is “Indian time.” Louie has a sign in the Band office saying, “Showing up on time means you care.” Chapter 4 deals with housing, Chapter 5 “Per Capita,” about funding distribution for the reserve, Chapter 6 on the “Indian Problem.” Chief Louie is not afraid to berate his own people who don’t pull their weight, an ethic he learned from his mother.

Chapter 7 deals with the residential schools and boarding schools. I saw Chief Louie and members of the Osoyoos Indian Band, many survivors of the Kamloops Indian Residential School, who visited Kamloops in the summer of 2021 in a caravan, Clarence on his Indian motorcycle.

Chapter 8 is about Native sports logos. Chief Louie, a dedicated sports fan, disagrees with the current elimination of the use of Native images – the “idea that wearing and using Native sports logos and names is being racist or insensitive to Native people.” Just the contrary, Clarence says, “Native sports logos bring together people who would otherwise never talk.” He quotes the Chicago Blackhawks organization, which states that: “The continued use of Native logos should be leveraged to create opportunity, create avenues of commerce and business, pathways for education and additionally create awareness of Native issues and concerns.”

Later chapters focus on economic development (and the success of OIB which has a long list of accomplishments) and on leadership. Louie speaks in depth on being a leader and the qualities that make a good leader. His election campaign has not changed for over thirty years, he says. “I’ll create more jobs and make more money for the Osoyoos Indian Band than anyone else” He never wants the OIB to be dependent on government grants. A footnote is in order here: Louie was a two-term chair of the National Aboriginal Economic Development Board. In 2003, he was chosen by the US Department of State as one of six Canadian First Nations leaders asked to review economic development in American Indian communities.

By “Rez culture,” Clarence is not referring to the Band’s traditional ways but to the colonial system imposed by the government, the legacy of the Indian Act. “We have to get back what I call a ‘working culture,’” Louie says.

Louie comes across as a serious man. Indeed, he has to be thick-skinned. But he also has a light-hearted side. I enjoyed his description of Rez humour, a common bond between Indigenous people. “We make fun of things that white people don’t get,” Louie declares, like “Rez bomb,” the decrepit cars driven on reserves, and “Indian squeeze,” piling as many people as you can into one of those cars.

On the subject of Truth and Reconciliation (Chapter 12), Louie states how he is bothered by “throwaway gestures” like land acknowledgement statements, “that do nothing to correct past injustices.” “Unceded” is a fancy word for “stolen.” To Chief Louie, true reconciliation means starting with the land, returning the original Indian reserves that were taken away by the government. In the case of Osoyoos Indian Band, 4,200 acres of Indian Reserve were “ripped away by a provincial magistrate.”

Louie has now served ten terms, winning every election but one. In that time he has won many accolades and awards. In 2004, he received the Order of British Columbia and in 2016 was made a Member of the Order of Canada. He was given the Freedom of the Town of Oliver in July 2017. In 2020 the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA) elected Chief Louie Tribal Chair and spokesperson of the ONA. He is also the current president of the En’owkin Centre in Penticton which offers Okanagan language and cultural-based learning.

Throughout the book, and especially in the final chapters, Chief Louie talks about leadership. Some may say that Clarence is a workaholic. “Native people have always worked for a living,” is a favourite motto of his. Chief Louie is not afraid to berate his own people who don’t pull their weight, an ethic he learned from his Mom. One of his rules is that he can’t work with anyone who can’t put in some time in the evenings and on weekends. But Louie makes time for everyone, just as he did for me.

About his legacy, when he retires from being Chief, Clarence Louie hopes to leave with a bang, not a whimper. His story ends with his love of biking and the memorial motorcycle rides. He quotes a biker saying: “Life’s journey is not to arrive at the grave safely in a well-preserved body but rather to pin the throttle and skid in sideways, totally worn out, shouting ‘Holy shit … what a ride!’” Chief Louie’s book ends with words that echo the theme of his autobiography: “Damn, I’m lucky to be an Indian!”

Rez Rules is a book for everyone – accessible and to the point, serious yet humorous – that deserves a place on home bookshelves, where it will stay for a long time on mine.

*

Ken Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and many certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, and four at the Osoyoos Museum. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press, and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartgraphica, Cartouche, and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and co-edited a commemorative history (forthcoming) for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold-rush journal of John Thomas Wilson Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. As an archivist and historical geographer he has undertaken research work for several Interior First Nations. He now lives in Kamloops. Editor’s note: Ken Favrholdt has also reviewed books by John Macdonald and Brett McGillivray for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1374 Chief Clarence Louie of Osoyoos”

Ken – not a bad review of the book! I have not read yet or been presented a free copy by CC the First.

Clarence I go away back and I think he was playing hockey at Oliver Arena when old “Buff” and Ron were cleaning the ice.

Both Clarence and I were in civic government for many moons over McKinney. I wish him sales but the story is not complete. He knows there is so much more to the story.

I take full responsibility for my actions in cooperating on so many projects with the OIB in the last 30 years and I would like to be recognized as a non-Indigenous leader who has tried to make a difference sharing history. If you need pix I can supply.