1348 Baffling thrums of reasoning

White Lie

by Clint Burnham

Vancouver: Anvil Press, 2021

$18.00 / 9781772141740

Reviewed by Peter Babiak

*

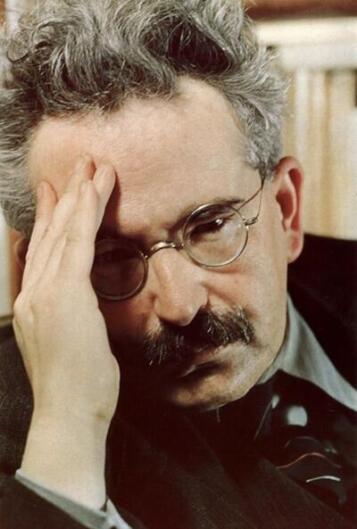

One of my favourite lines of literary theory is from the mystical German Jewish essayist, Walter Benjamin. A perspicacious man who recognized just how much literary works are indebted to the economic and technological conditions that form their historical contexts, he wrote during the formative years of mass media between the two world wars, but his work has become more relevant now that digital media supplanted electronic media and transformed every aspect of our lives. Benjamin opened his essay “One Way Street”, a surrealist montage of 60 short prose missives intended to mimic in their unruly structure the tempo of modern urban life in the 1920s, with a piece called “Filling Station”. In it, he argued that “true literary activity cannot aspire to take place within a literary framework” but must “nurture the inconspicuous forms that better fit its influence in active communities than does the pretentious, universal gesture of the book”. To simplify, though we fetishize literature, contain its production, consumption and even its understanding to rarefied quarters, “literary activity” increasingly happens every day, in “leaflets, brochures, articles, and placards”, the “prompt language” that surrounds us when we do mundane things like fill the car with gas. Today, Benjamin would likely say “literary activity” happens on screens, on social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Discord, and all those “prompt” and “inconspicuous” virtual spaces that enable “active communities” to write and be read.

One of my favourite lines of literary theory is from the mystical German Jewish essayist, Walter Benjamin. A perspicacious man who recognized just how much literary works are indebted to the economic and technological conditions that form their historical contexts, he wrote during the formative years of mass media between the two world wars, but his work has become more relevant now that digital media supplanted electronic media and transformed every aspect of our lives. Benjamin opened his essay “One Way Street”, a surrealist montage of 60 short prose missives intended to mimic in their unruly structure the tempo of modern urban life in the 1920s, with a piece called “Filling Station”. In it, he argued that “true literary activity cannot aspire to take place within a literary framework” but must “nurture the inconspicuous forms that better fit its influence in active communities than does the pretentious, universal gesture of the book”. To simplify, though we fetishize literature, contain its production, consumption and even its understanding to rarefied quarters, “literary activity” increasingly happens every day, in “leaflets, brochures, articles, and placards”, the “prompt language” that surrounds us when we do mundane things like fill the car with gas. Today, Benjamin would likely say “literary activity” happens on screens, on social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Discord, and all those “prompt” and “inconspicuous” virtual spaces that enable “active communities” to write and be read.

Benjamin’s argument is compelling because it breaks with the belief that literature should be held aloft, separated from the real world of the masses with their pedestrian affairs and uncouth bread and butter issues. I’ve thought about this uncomfortable truism over the years, and I thought about it again when reading Clint Burnham’s White Lie, an intelligent collection of 129 “super-short fictions” that looks and feels like an old-fashioned book but is best described as a series of fictionalized philosophical musings and reveries on the effects of the medium to which it is indebted for its “prompt”, disjointed form. The blurb on the back, you see, tells us that White Lie was “written on a phone” but is “intended to be read in a book”, an homage to real book reading from Anvil Press, the Vancouver publisher which is in the business of selling books that you can put on your shelf, even if those books are about the end of “the pretentious, universal gesture of the book”. In the spirit of Benjamin, a contemplative Marxist who was captivated by modernity, consumer capitalism, visual-based pop culture, and living at a time when new media technologies were shaping the cultural sphere, Burnham here offers eruptions of unbridled thought on how digital technology is reshaping how we read and write, what we read and write, and even how and what we think.

Flash fictions, microfictions, aphorisms, extended tweets don’t quite reach narrative cohesion, synecdoches of fully developed stories that must exist somewhere but not in this collection: whatever we call Burnham’s book, it is a thoughtful collection of fragments, not in the sense of a sentence fragment where grammatical flaws impede the production of meaning. No, these fragments are like the incomplete objects you’d expect to see at an archaeological dig or historical ruin, except it’s not history that Burnham is talking about; it’s today, and these stories are remnants of the everyday that are centrifugal to our own history in the making.

Many of his super-shorts are ephemeral peeks at simple experiences that aren’t really about anything other than the fact that they were probably experienced in this piecemeal way. In some, he seems to be applying something like Virginia Woolf’s “stream of consciousness” method to give us expressive, even poetic snapshots of characters in distinct historical and social contexts. The narrator in “Cold War Kids”, for example, reflects on living on a NATO base in West Germany, where he asks his dad “what team or side they were on”, to which the father says, “There aren’t sides,” which the narrator then follows up with two short clauses that house a incisive simile: “words like a scalpel, not a bludgeon”. “Bellow”, which opens with a comparison worthy of an evocative haiku, “A woman on welfare with ten illegitimate children is like a professor with tenure, neither has to work for life”, presents a man in a hot tub “in the bush near Pemberton” who asks a man and a woman in camouflage carrying rifles “you mind pointing that somewhere else?” Like fragmented photos or partially overheard conversations, this is all we get: unremarkable experiences rendered remarkable in their sheer writtenness. “Coda” opens with the hilarious question “Have you ever accidentally eaten cat food”, then one sentence later closes — incomprehensibly yet, keeping in mind the arbitrary association of ideas in anybody’s mind, skilfully — with a reference to the narrator’s kid who “wet his sleeper when he fell asleep on my charger and I don’t have any data”. In the hands of an intelligent writer like Burnham, this ability to start stories that we think should go someplace but don’t, this penchant for providing surface structure residue without bothering with deep structure details, leads to lyrical gusts of situational insight wrapped in simple, conversational language.

Most of his super-shorts, however, are observations on experiences directly inflected by the spirit of our technology-steeped age. In “Craigslist”, for example, a first-person narrator unfolds a routine incident involving strawberries wrapped in an old classified ad bought from a roadside stand. We don’t know anything about the characters — besides the narrator, there’s a woman and a child, a frequent cast that makes these fictions seem autobiographical — but the characters don’t matter here, not compared to the old newspaper wrapping, which is from the days “before Craigslist effectively killed that revenue stream.” It’s the minutiae that punctuate our lives, Burnham seems to be saying here, that’s changed while we weren’t paying attention, and throughout his collection these small things are defamiliarized so we consider them consequential. Like in “Screen Grab”, where the third person narrator — the collection swings mostly from first- to third-person narration — begins “Mo was not too familiar with his smartphone, but his daughter had taught him how to take a shot of whatever was on the screen”. There’s nothing at all about their relationship, nor even about the digital divide between them, which we might logically expect. Instead, in a rasping jump-cut, the next sentence just shifts to Mo and someone named Bob who is “complaining about what to do about his girlfriend, she was pregnant”, and obliquely wondering to himself why he never knew his friend’s name is short for “Mohammed”. A similar disjointedness materialises in many of Burnham’s tech-focussed fictions, like “Selfie in a Convex Mirror” and “Selfie-ish”. The latter, in particular, which vaguely follows the surrealist exercise of taking one thing and concentrating on it in the hope of arriving at its deeper meaning, is a list of places where an unidentified woman took “selfies”, and is emblematic of the oddly satisfying sense of incompletion we experience throughout White Lie, here in the form of repetitive sentences like “A selfie with the protests at Maidan, Ukraine, behind her. A selfie with Guernica behind her”. Admittedly, it might be hard for readers to find a point in the persistent discontinuities at first.

White Lie can be a bewildering read and it can be alienating, too, but to the extent that our lives today are tied to baffling thrums of technocratic reasoning that often leave us stumped, it is an intelligent read. Like a prose-poem from Baudelaire, the Parissiene flâneur who concluded that “looking from outside into an open window one never sees as much as when one looks through a closed window”, Burnham hopes to unlock messages about our administered postmodern world by presenting us with partial glimpses of it. One of his points, it seems, concerns subjectivity, which has been the underlying premise of novels since that genre was invented a few hundred years ago, and short stories, too. Rounded characters of the sort we read in conventional fiction are uninteresting to him, a bourgeois indulgence that is never as important as material history in which individuals do their living. The disruptions posed by Craigslist, the meta-art of screenshots, the simple fact of selfies, all of which would have been unthinkable not too long ago but are now considered second nature, show us that what was once a locus of our desires will also always be supplanted by some newer product or gadget. In this, he’s admirably illustrating the significance of historical materialism, the old Marxist way of thinking that’s sadly become obsolete in our technocratic age. Theodor Adorno, one of Benjamin’s colleagues in the Frankfurt School of thinkers, and someone whose aphoristic style is reminiscent of Burnham’s project, said that splintered, partial thought gives form to contemporary life, and that if we want to “experience the truth of immediate life” we “must investigate its alienated form … which determines individual existence.”

As a theoretically-inclined writer with a taste for mass market culture, a number of Burnham’s fictions are so hooked into pop culture that they seem too whimsical to be taken with the gravity that historical materialism requires. In “Toes”, for example, we have an irreverent meditation on Kevin Spacey’s acting career that in the space of a few sentences moves from the 1980s TV show Wiseguy, through the unforgettable The Usual Suspects of the 1990s, to “s03e06” of House of Cards, the last program only referenced by alpha-numeric seasonal coding, a nod to the episode classification system. As a side note, when I looked up seasonal coding online, I found an entry of over 2000 words long on TV Tropes dedicated to “Episode Code Number”. In the three “Bosch” vignettes, named after a 2014 Amazon TV series based on Michael Connelly’s detective fiction — subtitled “Fan Fiction” (I, II, and III) here — Burnham presents three fractional narratives that flit across a hodgepodge of themes — making the LAPD more palatable to people in South Central, Chris Penn, Hieronymous Bosch, and so on — in a manner that befits our society-wide attention deficit disorder. In “Rap? Sure”, the perfunctory narration focalizes on someone at a navy hospital in Esquimalt, a sliver of local colour that’s interesting but not nearly as important as the music citations that situate the piece in the 1980s: The Clash’s Give ‘em Enough Rope, the B-52s’ “Rock Lobster”, and Blondie’s “Rapture”.

For all the allusions in White Lie — from Nespresso, hoodies, Mad Max, iPods, DQ Blizzards, to Derrida, Melville, and Rubens — these shorts are poetic gusts of insight packed into tight prose missives that suit the accelerated undulations of our times. Take, for example, “Raise the Lever of Self-esteem”, where the narrator writes about a “communications professor” who believes that “skimmability” is “a prime prerequisite in the new ‘infowhelm’ society”. We’d like to know more about this professor, but again, nothing is offered; we’d like to know more about both her neologisms, too, but they’re just there, unexplained pieces of shrapnel from the disruptions that mark what the great Canadian theorist Harold Innis called “the bias of communication”, the manner in which any communication technology — film, TV, books, the computer—makes its users in its own image.

By far the most engaging shorts are those on the subject of writing and on photography, where we come closest to sussing out Burnham’s technologically-determinist aesthetic. In “The Prophet”, to take just one of many shorts that focus on writing, we learn that the protagonist—the ever-elusive “he”—“was writing an article about a media prophet”. The thing is, “He would not be writing, would be taking a break, watching a TV show he had downloaded illegally, and then an idea would come into his head, would just pop into his head was how he would think of it.” The piece is really about the perpetually distracted state that, somehow, provides the “germ of an idea” and, as the narrator tells us, it is the technology that scaffolds his thinking: “he wasn’t sure what the metaphor would be, if the idea was a virus that spread from word to work as he wrote, or if it was in his brain and his writing was working on his brain, making the idea take form.” On the subject of photography, Burnham’s work is just as pressing and even more reminiscent of Benjamin, who wrote about how the technology of photography and film change how we see and think. “Some Objects”, for instance, is on the piecemeal nature of photography and how every act of visual framing implies an exclusion. In “My Practice” the third person narrator — dissonantly, given the first-person singular possessive pronoun used in the title — recounts how “he” would “write four of five of the stories — he still thought of them as photographs that developed over time — in a morning or afternoon”, and then — recount the detailed method by which he proofed his work: he would put them into a Word document on his laptop, convert it to a PDF, put that into the cloud, then on his tablet open the stories in a PDF reading program, take a screen shot of the pages, open the camera, look at – read — them. As he says in another photography-based story, “One cannot help but think that there is a request being made: Read as you would see or look at an image, or photo.”

On the one hand, what Burnham is doing here is not new. The Wikipedia entry for “cell phone novel” indicates that it “is a literary work originally written on a cellular phone via text messaging” and that its “chapters consist of about 70-100 worlds each due to character limitations on cell phones.” Apparently, in 2007, half of the ten best-selling novels in Japan were cell phone novels. They started trending in the west, too, around the same time, with YA novels like Lauren Myracle’s ttyl and l8r, g8r, which simulate instant messaging on pages made to look like online chats. Hooked, an iPhone app developed in 2015, lets anyone — but mostly kids — compose or read “stories” made entirely of text messages exchanged by fictional characters. Mind you, not all of these digitally inspired ventures are written to profit from the fact that, attention spans not being what they once were, narratives have to fall in line with a reduced ability to sustain a thought. Douglas Coupland, for one, was doing this in his 1995 Microserfs, an epistolary novel that first appeared as a short story in Wired, where the narrative is presented in the form of diary entries written on a PowerBook laptop, complete with emoticons and blog formatting.

On the other hand, Burnham writes with a degree of philosophical mettle that is not always present in the many celebratory takes on technology. Infuriatingly fragmented, marked by arbitrary stops and starts, unhampered by the supplies we covet when reading conventional stories — character, plot, sentences that lead logically one to the next — his reveries are clearly indebted to the anxiety-laced aesthetic by which we live today. Like listening — perhaps “watching” is a better word here — to a speaker at a TED Talk while texting your friend about it and posting a picture of yourself at the event and then scrolling through your feed to see how many people have liked it, reading White Lie is like celebrating the carnivalesque transformations that our world has forced upon us and that we have, in turn, embraced. Similar to the vignettes in Benjamin’s “One-Way Street”, these super-shorts are enticements to experience the materiality of our digital world in its stark simplicity. On reading Benjamin, Susan Sontag once noted that it is as if each of his sentences “had to say everything, before the inward gaze of total concentration dissolved the subject before his eyes”. Burnham is not quite Benjamin, but there is something similar at work in his work that makes it a vital read today.

*

Born and raised in the GTA, Peter Babiak now lives and writes in East Vancouver. He teaches linguistics, composition, and English Lit at Langara College, and writes for subTerrain Magazine. His commentary and creative nonfiction has been nominated for both B.C. and national magazine awards and his collection of essays — Garage Criticism: Cultural Missives in an Age of Distraction, published by Anvil Press in 2016 — was a Montaigne Medal finalist and an Honourable Mention in the Culture Category of the Eric Hoffer Awards. His work was selected for The Best Canadian Essays (Tightrope Books) both in 2017 and 2018. He has a dog, a cat, a garden, and an alluring garage. Editor’s note: Peter Babiak has reviewed books by Stan Rogal, Jamie Lamb, and Gilmour Walker, and his own book Garage Criticism was reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1348 Baffling thrums of reasoning”