1224 No laughing matter

The Comic

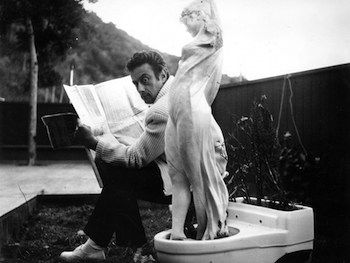

by Stan Rogal

Montréal: Guernica Editions, 2020

$20.00 / 9781771834827

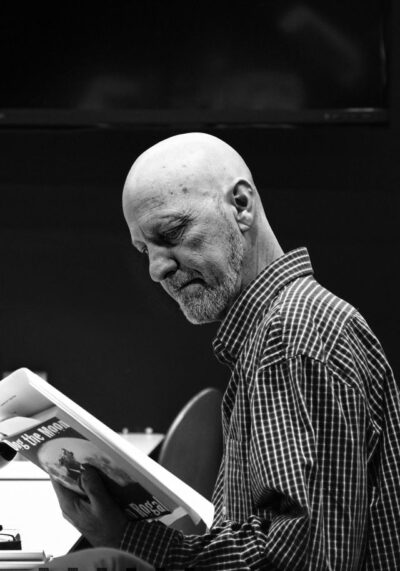

Reviewed by Peter Babiak

*

The Comic is a novel about a sad sack of a college English teacher, Mark Nowakowski, who runs up against surreal Kafkaesque forces when he breaches the unwritten rules on linguistic expression that have become hot-button issues in western liberal democracies. Stan Rogal’s novel resonates with me mostly because its provocative protagonist, in his second job as an untried stand-up comedian, thinks out loud about notorious—and notoriously misunderstood—issues that attend buzzwords like “triggering,” “wokeness,” and “cancel culture,” all of which appeared first in the rarefied world of academia about a decade ago but have since become mainstays of public discourse. These catchphrases, along with the clause “freedom of expression”, which is often misinterpreted as a person’s “right” to use language as they wish, have vexed me for many years and have altered how I do my job. Let me explain.

The Comic is a novel about a sad sack of a college English teacher, Mark Nowakowski, who runs up against surreal Kafkaesque forces when he breaches the unwritten rules on linguistic expression that have become hot-button issues in western liberal democracies. Stan Rogal’s novel resonates with me mostly because its provocative protagonist, in his second job as an untried stand-up comedian, thinks out loud about notorious—and notoriously misunderstood—issues that attend buzzwords like “triggering,” “wokeness,” and “cancel culture,” all of which appeared first in the rarefied world of academia about a decade ago but have since become mainstays of public discourse. These catchphrases, along with the clause “freedom of expression”, which is often misinterpreted as a person’s “right” to use language as they wish, have vexed me for many years and have altered how I do my job. Let me explain.

One morning many years ago, I was sitting in a lecture hall where my English prof was talking about Mordecai Richer’s 1968 novel, Cocksure, a tingling satire aimed at taking down the hypocrisy of 1960s social justice rhetoric. I was roused out of my stupor when he read out a passage spiced with more F-bombs, C-words and other profanities than I thought could comfortably fit into such a few sentences. He laughed, and of course most of the students did, too, and that shared laughter was, I think, the effect of having the conventions dictating which words could and could not be said aloud in an academic context, and by whom, collapse. I adored that class. We read books by writers who believed that the vice of inappropriate words in the service of literary craft and social satire is more virtuous than any virtue signalled simply by using appropriate language. Richler’s book was a draw because we learned that it was banned by W.H. Smith in Britain—and if it was banned, it must be good—but we also read works by Bertolt Brecht, Joseph Heller, and Kurt Vonnegut, whose foreword to Breakfast of Champions taught us that it’s good to be “impolite in conversation not only about sexual matters” but about “history and famous heroes, about the distribution of wealth, about school, about everything.” For all the “impolite” literature we read, there was no trigger warnings, no tedious meta-conversations spent dissecting any microaggressions latent in the words on the page.

About fifteen years ago, when I had already been teaching post-secondary English for a few years, I pitched a class loosely modelled on my old class. I called it “Word Crimes” and I used Kafka’s well-known aphorism, “A book must be an ice-axe to break the sea frozen inside us,” as its unofficial epigram. It was quite popular for a few years, regularly attracting more students than there were available seats. We read books like Lolita, Howl, and American Psycho, and discussed literary, linguistic, and legal issues related to the question of obscene and offensive language. After about five years, I stopped teaching “Word Crimes” and decided against teaching a few of the more “impolite” readings I’d taught in other classes, too. The college English class had, in a short time, changed beyond recognition, and I got tired of dealing with student grievances about what I was teaching. Caitlin Flanagan, in a 2015 essay for The Atlantic, encapsulated the shift on campuses this way: “college students … have internalized the code that you don’t laugh at politically incorrect statements; you complain about them.” Apparently, these “statements” include sentences in works of fiction. Now, I don’t put much stock in most criticisms of “woke” college students—not since President Trump and his band of anti-intellectual populists weaponized “cancel culture” for their own ends—but there’s just no way I’d go back to teaching books like that today, certainly not satirical novels like Cocksure. A cursory glance at a few recent armchair judgments posted on Goodreads might help to explain why: “a foul-spirited and foul-mouthed work,” “a forum for sex talk bordering on vulgarity,” “dated, misogynistic, anti-Semitic, anti-gay, and anti-black…an unpalatable serving of political uncorrectness.” What was a laughable insight when I was a student, it appears, has become unspeakable today.

I heard one complaint in the first decade I taught post-secondary English. It came from an Evangelical student who refused to read José Saramago’s The Gospel According to Jesus Christ because it offended his beliefs. But then, for reasons that I still can’t entirely comprehend, the complaints increased exponentially ten years ago, though I should stress that the plaintiffs have only been a vocal minority. One student went to see my department chair to announce that he was dropping out of my Creative Non-fiction class after the first day because the David Sedaris essay I handed out as the first reading featured too many swear words. A student in my Literary Theory class accused me of sexism because I didn’t include a question on “Feminism” on the quiz, although that wasn’t a theory we covered in that class. One student called me insensitive to his Jewish faith in class for teaching a book by Northrop Frye, who wrote that the Bible should be the foundation of a sound literary education; a self-professed Christian student in the same class told me he was upset when, to assuage the first student, I told the class they should feel free to replace Frye’s use of the Bible with any sacred “myth.” A student in a Linguistics class objected that teaching argumentation—some arguments are valid, some are not—is wrong because it is “binary” and might “trigger” some students, presumably nonbinary ones. Two students in my Traditional Grammar class complained to my boss that a handout I’d given them the day we were studying Cicero’s classical Cataline orations was “triggering.” The handout, which consisted of a single paragraph drawn from then-US Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanagh’s ambling self-defence against accusations he’d assaulted Christine Blasey Ford when they were both teenagers, was intended as a contrast to Cicero’s model speech wherein he was trying to persuade the Roman Senate to have someone executed.

Enter Stan Rogal’s protagonist, Nowakowski, the part-time English prof and rookie stand-up comedian who goes by the name “Bruce Leonard,” an homage to Lenny Bruce, the iconic comedian and social commentator who in 1961 was charged with obscenity for, among other word crimes, saying that “’to’ is a preposition, ‘come’ is a verb.” A jury acquitted the original Bruce, but police still made appearances at his gigs, often arresting him on the charge of uttering “obscene” language. In a similar vein, the police monitor our Bruce at the Comedy Pit, the fictional Toronto venue where he makes his debut as a comic and delivers two particular jokes—one racist, one sexist, both “funny” (in scare-quotes)—that function as the plot enabling device for the novel and the driver of all Nowakowski’s problems, of which there are many, ranging from a marriage break up to drug addiction. I should note that, although our Bruce notices the police at the Pit, he remains somewhat acerbically oblivious throughout the story as to how it is that his words can elicit such an insidious effect on people.

And herein lies the linguistic question which stands behind the conflict in this novel and is the driver of the protagonist’s own undoing. “’So,’” he asks his Pit audience during one of his first sets, “’is it the actual act that’s the problem, or the language itself that’s the issue?” He happens to be riffing on the colourful English expressions for masturbation, trying to rouse the crowd with their assorted metaphorical colour (“Spanking the monkey. Choking the chicken. Greasing the gash, Paddling the pink canoe”). How, he asks them with a rhetorical question, can an innocuous replacement phrase like “self-pleasuring” be “socially acceptable” when it signifies the exact same act as “beating the bishop”? In his role as the comic, Bruce just doesn’t get it, but of course his characterisation as an ingenue in matters of offensive language is part of his routine. As much as his bit about figural code words for onanism might grate on sexual conservatives, in the context of discussions on public uses of language that question should never be sidelined: “If you can’t change the behaviour, simply change the terminology,” he says imitating the superficial reasoning behind policing language, to make what you want to talk about sound “kinder, gentler.” The same kind of question underpins many of the pressing issues today, particularly as they relate to matters of linguistics representation, like racism and sexism. And still the same question lingers over the entire narrative. How can certain words and word combinations be acceptable when these words and phrases are not the things they signify, but only signifiers for those things? René Magritte, in his renowned 1929 painting of a pipe underwritten with the seemingly counterintuitive statement, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” put that same question into stark relief, and yet the answer eludes us because we are attached to connecting signifier and signified, though we know that the relation between a word and its meaning is, with the exception of onomatopoetic words, entirely arbitrary and so outside any person’s subjective motivation.

In any case, the pragmatic significance of Bruce’s two offensive jokes is clarified to him, first, by his wife Rebecca, a consistently bitchy banker who just doesn’t seem to like her husband much, telling him his jokes are “racist and sexist,” and then by two slightly more sympathetic students who approach their professor after his Monday class to warn him about “the YouTube video going around, with the two jokes you told.” Rogal’s narrative often points the finger not at people who actually find language offensive but at the speed at which a person’s life can be destroyed with a mobile phone that can fire anything onto social media, and there’s a truth here regarding the critique of technology that, to me, should be more central in the narrative than the critique of people’s fragile linguistic sensibilities. This is the reason comedian David Chappelle bans phones from all his club shows, and even his comparatively tame colleague, Patton Oswalt, has expressed reservations at trying new material in front of an audience when anybody listening can press record and instantly post a practice run out of context to social media.

The fact that our protagonist happened to be lecturing on Kafka the day his students approach him is entirely fitting, given that this news initiates his steady undoing over the course of the narrative. He loses his job and splits with Rebecca, whom he finds in flagrante delicto with her coworker while engaged in some loquacious “dirty talk” (sex being a forum where inappropriate language is still appropriate, apparently), he takes up residence in an EconoLodge motel downtown and lives on Dollar Store peas and crackers, he experiences a series of strange encounters with administrators and authorities at a place called the Court of Justice that are more metaphysical than juridical and clearly influenced by Kafka’s take on power in texts like The Castle and Before the Law, he enjoys some publicity on a TV Show whose host and audience clearly want to ridicule him just because they can, he engages too liberally with drugs and alcohol, and he finally acts out at a Niagara Falls casino with a real gun on stage in a nihilistic episode at the end of the novel.

Apart from its engrossing protagonist, this is a novel that should be read as a roman à clef, tied as it is to the question of what counts as comedy and what doesn’t in a society that experiences sharp swings in mood and taste on issues of offence and sensitivity. The analogue for Rogal’s work is the so called “death of comedy,” an alarmist slogan that some news sources, many unfortunately affiliated with those on the ideological Right, have taken to invoking in the last few years. Veteran funny man, Mel Brooks, was one of the first to use the line, telling the BBC in 2017 that he would not be able to make his classic film Blazing Saddles today because of the “stupidly politically correct” animus heralds “the death of comedy.” Two years earlier, Jerry Seinfeld told Seth Meyers that “there’s a creepy PC thing out there that really bothers me,” and around the same time, Gilbert Gottfried argued, with the help of a cheeky simile that some will read as offensive, that comedians have “to treat the entire world as if it’s your wife or girlfriend,” which means that “everything you do is probably wrong.” Rogal’s protagonist falls into this line up of funny men—along with Chris Rock, Bill Maher, John Cleese, Norm MacDonald—who are experiencing the culture shock of umbrage and offended feelings that started in academia, with its decade’s long embrace of “identity politics,” but has since migrated into area of the world—social, political, corporate and, of course, cultural and comedic.

In one of the more dynamic episodes of The Comic, Mark is the featured guest, along with pop culture icons Jessica Simpson and Miley Cyrus, on The Barry Kendal Show. The host tries to command the narrative about the “charges” of racism and sexist Bruce Leonard faces, but Mark is more interested in calling attention to the fact that the emperor wears no clothes, which is never what the people want to hear. He answers all Barry’s questions, reminds him that he has “not been formally charge with anything nor has anyone taken the time to personally tell me what the list of charges are or might be,” though he spends more time demystifying how the culture industry works, calling attention to the safety mechanism of the time delay on seemingly spontaneous TV shows to eliminate unwanted language, the lack of originality in plotting heavily scripted mainstream narratives, and the corporate advertising that sustains the entire business, which Barry rightly—though too verbosely for TV—says “is the type of thing that should be labelled obscene and criminal.” Mark calls out Barry for using the secure expression “the ‘N’ word” when he broaches the “charges”, launches into a fragile defence of using the word which people do find offensive, asking the host “how are we expected to have an intelligent conversation when we can’t even say the word? … The word is nigger, Barry. Nigger. You don’t change the world by talking a felt pen marker to Huckleberry Finn and pretend it was never there.”

He then obliquely references an episode at the 2014 Oscars when host Ellen DeGeneres told the audience that the evening could only possibly end in one of two ways: “Possibility number one: 12 Years a Slave wins best picture. Possibility number two: You’re all racists.” It’s no secret that best film award often has more to do with redressing past social wrongs than it does with cinematography, but Mark points that DeGeneres’ joke “was another example of a thoughtless remark cloaked in a veneer of ‘cultural sensitivity’ but is itself racist and inflammatory. Worse, it smacks of elitism: I’m more culturally sensitive than you, because dot dot dot …” I can’t help but think there’s a significant point here.

We forget, sometimes, that comedy may be a matter of individual taste and preference, but it has a history that positions it as something of a levelling salve against the corrosive aspects of life itself, especially among those who don’t enjoy the luxuries of wealth and influence. The Comic, though it’s unlikely to settle any questions readers might have on “freedom of speech” and its limitations, does open up some big, uncomfortable questions, which readers should appreciate because comedy does have a venerable history. In The Poetics, Aristotle points out that comedy “originated with … the phallic songs,” which reminds us that the genre is always a stone’s throw away from a celebration of sexuality and eros, and which also explains the compulsory and sometimes puerile sex jokes in so many stand up acts. The Russian writer Mikhail Bakhtin says something similar when he pointed out that comedy is a festive liberation from social restraint. Specifically, it involves “the lowering of all that is high, spiritual, ideal, abstract” and “a transfer to the material level, to the sphere of earth and body in their indissoluble unity.” Early in The Will to Power, Nietzsche writes “I know best why man is the only animal that laughs: he alone suffers so excruciatingly that he was compelled to invent laughter. The unhappiest and most melancholy animal is, as might have been expected, the most cheerful.” That’s certainly the case for many comedians, many of whose funny lives are marked by acute mental and physical pain—Robin Williams, for example, Charles Rocket, Brody Stevens, and Andrew Koenig, the actor/comedian who took his life and was found by friends hanging from a tree in Vancouver’s Stanley Park in 2010.

Mark experiences a similar degree of suffering. One evening before his gig at the Pit, he notices the police still in attendance and wonders why the place is packed. Maybe there’d been more rumours online that he’d been charged with smoking crack of raping a nun, he wonders. “He didn’t care anymore. It was all entirely too nebulous and nothing he could do to control the situation anyway. Instead, he concentrated on refining and delivering his latest routine.” From this point, things get almost too-dramatically worse. He has a bizarre encounter with his friend, fellow comedian, Brenda, the only person who has his back, but who later commits suicide herself; he significantly ups his intake of narcotics; he is fired from his future shows at the Pit; he is forced to vacate his hotel room because the maid found drugs there and then posted the news online; and, with the help of a calculating Czech publicist, his wife appears on Barry Kendal and says, among other defamatory things, “I had no idea I was living with such a sick and twisted individual until the time he went on stage and presented himself in such a vile and deviant manner.”

More important than any philosophy of comedy, though, is its philological component. All novels, though inspired by peoples’ real life experiences, are machines made of words. Whether we like it or not, understanding its prose, like popping the hood of your car to see how it works, requires sensitivity to form and technique, not sensitivity to morality and propriety, even when we forget that words and the things they signify are, in fact, separable. Near the end of the novel, we are confronted with the same question Bruce Leonard has been asking himself and his audiences since the beginning:

The question is—how do comics manage to negotiate themselves through all the minefields and shit storms that are out there? What topics are available? What materials can be used? What can be made funny that isn’t going to piss someone off?

And like all matters of language, this question is next to impossible to resolve, which explains Nowakowki’s downfall and why the book ends on an absurd, nihilistic note. In the context of the novel, the question what constitutes polite and impolite language requires the tact and patience of a philologist to address; it is not something that should be addressed in a hasty Facebook or Tumblr post or in a Tweet that by its very nature is more of an articulation than an invitation to a dialogue. And yet, like it or not, these are the forums of public discourse today. Any self-respecting English prof like Rogal’s protagonist should know a thing or two about how language, far from being a passive mirror up to reality, creates and frames reality. In the guise of “Bruce,” Rogal’s protagonist is an admirable sort who falls short of this knowledge.

A middle-class white guy is an admittedly difficult characterisation to pull off these days without charging him with “privilege,” but as a literary character we need to approach him with patience and understanding not with rehearsed judgements. He doesn’t know why things are the way they are in the world, not just the sometimes breathtaking inanity of politically-correct culture, but the creepiness of celebrity culture, the narrative of the news cycle, and the aesthetic of branding that defines the social media context which has replaced the news media as our source of information. A socially and administratively inept man who drinks and does drugs, he a buffoon cut from a stock character template that reminds me of old school literary types in the novels of Kingsley Amis and Milan Kundera. Though I think he is fundamentally right in his criticisms of PC culture and the culture of sensitivity, he has several flaws, as we all do, and one of them is his inability to fully grasp that language is an immensely social fabric, not his own personal material for individual expression. His liberty to say what we wants to say is, in the constitutional framework under which we operate in this country, no more important than everybody else’s liberty to be free from having to hear it. Nor is it any less important, though.

I enjoyed this novel more than I thought I would. True, it made me wary of the grievances I’ve heard as a teacher and prompted me to defend the protagonist by writing in the margins of a few pages more than a few times the phrase “tolerance is not acceptance”. It also made me consider reconsidering why I teach the material I teach and, more importantly, try to comprehend how other people might be harmed by some language, though I don’t think they should be even as I accept the linguistic premise that our language creates and frames so much of what we consider our reality. Fortunately, I don’t have anywhere near the authoritative presence in my environment because a comedy club is a market venue, whereas a college classroom is not.

*

Born and raised in the GTA, Peter Babiak now lives and writes in East Vancouver. He teaches linguistics, composition, and English Lit at Langara College, and writes for subTerrain Magazine. His commentary and creative nonfiction has been nominated for both B.C. and national magazine awards and his collection of essays — Garage Criticism: Cultural Missives in an Age of Distraction, published by Anvil Press in 2016 — was a Montaigne Medal finalist and an Honourable Mention in the Culture Category of the Eric Hoffer Awards. His work was selected for The Best Canadian Essays (Tightrope Books) both in 2017 and 2018. He has a dog, a cat, a garden, and an alluring garage. Editor’s note: Peter Babiak has reviewed books by Jamie Lamb and Gilmour Walker, and his own book Garage Criticism was reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1224 No laughing matter”

I only recently discovered this review of my book. Can you please thank Peter for such a kind, thoughtful, intelligent, in-depth and fearless examination of my novel and its themes. I am truly grateful.