1265 Broken from the beginning

No Man’s Land

by John Vigna

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021

$22.95 / 9781551528663

Reviewed by Carol Matthews

*

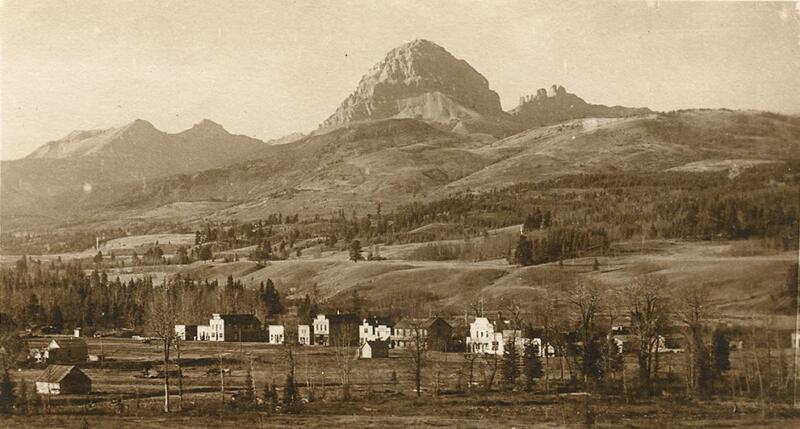

I really don’t like violence in fiction — surely there is enough of it in the world around us — but I was drawn into John Vigna’s No Man’s Land because of the powerful beauty of the landscape and Vigna’s muscular prose in describing it: “the wind scrubbed the alpine clean and cirrus sky was tufted with streaks like mare’s tales, the land yellow and tawny, lacerated by brown trails and the green river.” Set in the Canadian Northwest at the end of the nineteenth century, Vigna portrays a world of violence and depravity in which people pursue personal pilgrimages across a treacherous terrain.

I really don’t like violence in fiction — surely there is enough of it in the world around us — but I was drawn into John Vigna’s No Man’s Land because of the powerful beauty of the landscape and Vigna’s muscular prose in describing it: “the wind scrubbed the alpine clean and cirrus sky was tufted with streaks like mare’s tales, the land yellow and tawny, lacerated by brown trails and the green river.” Set in the Canadian Northwest at the end of the nineteenth century, Vigna portrays a world of violence and depravity in which people pursue personal pilgrimages across a treacherous terrain.

Throughout the novel there are many references to the King James Bible and, from the outset, the narrative has a biblical feel:

In the beginning, a land, void, without form…. Oh heavenly presence, lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the void… as though in prayer, aspen, birch, cottonwood, bushy alder and willow leaned over the roaring water.

The description of the early world is abundant with a wondrous array of sky-blue lupins and wild-pink geraniums and every species of flora and fauna, beasts and birds and whitefish and salmon. The First People arrive and adapt to life on the plains, and then come the “sallow-skinned Europeans” who seize and occupy and plunder, claiming the land as their own.

On the crest of Crowsnest Pass, Will and his father are given a warning from the wind to go home and to take only what they need to survive another year. A choice. The warning is not heeded and the choices that are made are almost all bad ones.

Will’s journey begins with a curse. His father says that Will’s grandfather had condemned him when he was not yet an hour old, declaring that he had the hands of a thief. According to his father, Will was “broken from the beginning” and that he is fulfilling his fate. The question of fate versus self-determination is explored and discussed throughout the novel.

At the heart of the story is Will’s daughter Davey, a fourteen-year-old girl whose mother died in a bloody massacre when Davey was an infant. Davey is taken in by a collection of thieves and murderers led by a charismatic preacher. Reverend Brown, a small man in a black cassock with a crown of cedar twigs, is captivating, eloquent and debauched. He drinks and dances with whores, kidnaps, tortures, murders, steals, and bears a stolen cross above his head, chanting bits of Latin as he parades about with his drunken disciples. And yet, when he delivers sermons and offers baptism, his congregation cheers.

Some people doubt whether Reverend Brown is truly a man of god, but it is only Davey who confronts and questions him. “You talk to avoid the truth,” she says, and “Your saying so doesn’t make it true. I see you. I’ve always seen you.” Davey stays with this bizarre tribe in part because she wants community and is seeking family. At first she is trying to learn who her father is; later she is searching for her own lost child. Davey is a seeker, and is seen by others as a fine and courageous person.

Reverend Brown is a persuasive and often poetic orator who claims to “move in mysterious ways.” A trickster who allows people to think he performs miracles, he insists that all our actions are part of a preordained path: “It does not matter what fork you choose, what you believe, it will still lead you there…. To move is already part of your fate.” Davey claims that she chooses her own way, but he argues that freedom is illusory.

“Unflinching” is a word that has been used to describe Vigna’s earlier book, Bull Head, and the description applies here as well. Much that is vicious, violent and horrifyingly cruel is faced in No Man’s Land. There are massacres, drunken brawls, slaughter of animals, rape, child abuse, torture and every kind of ugliness. About the of killing of people and animals, Davey observes that some of the men are “not happy unless they’re killing something.”

Yet there are also points of light both in the resilience of the landscape and in the many acts of kindness and generosity. Sadly, the wind’s warning to take only what was needed was ignored, and towards the end of the novel an old man talks about the loss of the bison, about gold, coal, logging and killing of animals, and says, “Getting the trees down as fast as they can and cartin’ all of it elsewhere. Ain’t going to be nothing and nobody left but the men who brought this on themselves. And then what?”

Vigna’s writing has been compared to Cormac McCarthy, William Faulkner and John Steinbeck, but for me No Man’s Land recalls the landscape, complexity and deep symbolism of Sheila Watson’s The Double Hook and in the balancing of good and evil and light and darkness. I recall an observation Wilson made about how people, if they have no mediating rituals, are driven towards violence or insensibility. There’s certainly plenty of violence and insensibility here, but there are also some mediating rituals such as the touching scene in which Fumiko tenderly bathes and cares for the wounded Davey. There’s a sense of communion in the sharing of bread and water that Smith brings to Davey. And there’s the leather sack that Davey has carried on her waist and passes on to Grace, the girl she has rescued and named. The sack contains small relics of Davey’s history, and pieces of cloth from Grace’s people.

Reading this novel is not always a comfortable experience, but the book is well worth exploring and perhaps reading more than once. And, when the world falls silent at the end of the novel, there’s a reassuring suggestion that Grace, and perhaps some hope and charity, will continue.

*

Carol Matthews has worked as a social worker, as Executive Director of Nanaimo Family Life, and as instructor and Dean of Human Services and Community Education at Malaspina University-College, now Vancouver Island University (VIU). She has published a collection of short stories (Incidental Music, from Oolichan Books) and four works of non-fiction. Her short stories and reviews have appeared in literary journals such as Room, The New Quarterly, Grain, Prism, Malahat Review, and Event. Editor’s note: Carol Matthews has also reviewed books by Hiromi Goto, Anita Lahey, Ivan Coyote, and Tamara Macpherson Vukusic for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1265 Broken from the beginning”