1257 China’s human rights orthodoxies

Exporting Virtue? China’s International Human Rights Activism in the Age of Xi Zinping

by Pitman B. Potter

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021

$32.95 / 9780774865562

Reviewed by Larry Hannant

*

With the resolution of the three-year saga of the 3 Ms (the two Michaels and Meng), British Columbians might be thinking they’ll get a break from the high-noon standoffs between China and the West and can return in good conscience to watching their made-in-China smart robot lawn mower make short work of that backyard crabgrass.

With the resolution of the three-year saga of the 3 Ms (the two Michaels and Meng), British Columbians might be thinking they’ll get a break from the high-noon standoffs between China and the West and can return in good conscience to watching their made-in-China smart robot lawn mower make short work of that backyard crabgrass.

They’d be deceiving themselves, of course.

In fact, the sparring has just begun in earnest. Vigilance is going to be needed to limit it to no more than a clash of legal briefs at dawn.

In the 21st century, China has become a capitalist powerhouse with an economy now second only to that of the US. Economists project it to be number one in total gross domestic product by 2028. Cold War analogies are more and more frequently used, but the US-China competition differs sharply in one important respect — the Soviet economy was never more than 40 per cent of its US rival’s. The Chinese are coming, armed with capital, commodities and crypto.

Flush with success and cash, China has striven to win new international prominence, reaching out to the world in a variety of ways. One form is investment in infrastructure, most prominently through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), introduced in 2013. It aims to funnel unprecedented capital into Asia, Europe and Africa, with a cornerstone element being an ambitious system of roads, railways and ports throughout Eurasia that will promote trade and development in regions that have been remote and poor. Another Chinese breakout strategy was the founding in 2004 of the Confucius Institutes, intended to promote Chinese culture, history and language abroad. Thirteen of them have been established at Canadian universities, and more than 500 exist internationally.

China’s advance into the majors has been met with Western resistance, some of it military. Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, founded in 1949 to confront the Soviet Union in the Atlantic and Western Europe, have established a persistent armed presence in the South China Sea. Naval and air force units from the US, France, Germany and Britain, among other countries, hoisted the flag in the area in the first half of 2021 alone. Canadian naval ships pass regularly and ritually through the Taiwan Strait, although at press time no Chinese naval vessels had been sighted in the Strait of Georgia.

Western states have also formed a common front to isolate China economically. It’s too late to halt Volkswagen and Tesla from assembling autos in China, but under US pressure Huawei will be barred from providing 5G internet service anywhere among the aligned states. In Canada, that means one less competitor in the race to ensnare the country in high-tech webs, so consumers will shell out more to the telecom cartel of Rogers, Telus and Bell.

Macro-economic and ocean-straddling offensives against China may be arcane to many Canadians. A polemic that does grab more people emotionally is the issue of human rights. A Western offensive on that issue is also being mounted. A sign of this is evident in a search of the New York Times for references linking China to human rights, revealing a dramatic increase in articles. A total of 354 entries in the year 2000 rose to 833 in the year 2020.

Increasingly, we’ve seen a full-throated condemnation of China’s human rights practices, carried out by such paragons of human rights as Mike Pompeo, Donald Trump’s secretary of state, who fondly recalled his earlier days as CIA director, saying: “We lied, we cheated, we stole.” But that was then. None of that’s being employed now in the effort to portray China as a ruthless regime marked by flagrant contempt for rights — whether it be the demand for democratic government in Hong Kong or the conditions of minority Muslims in Xinjiang province.

In Exporting Virtue? Pitman B. Potter takes the human rights issue beyond China’s domestic situation, arguing that it has adopted a new “international human rights activism,” which “seems mainly to be an exercise in justifying authoritarianism” (p. 10). Its fundamental agenda is “to alter international standards to conform to its human rights orthodoxy” (p. 45). That orthodoxy is founded on precepts that the Communist Party is the country’s exclusive political leader, that rights are conditional on loyalty to the party, and that the state, rooted in social and political stability, ensures economic security.

Pitman has previously written on China, trade and human rights in Assessing Treaty Performance in China: Trade and Human Rights (UBC Press, 2014). Venturing further afield, he has co-edited, with Ljiljana Biuković, Globalization and Local Adaptation in International Trade Law (UBC Press, 2012). A Professor of Law Emeritus at the Peter A. Allard School of Law at UBC, he has a deep familiarity with international trade law and how China interacts with it. He knows his international trade regulations and processes. His Authorities Cited section is dense with references to agreements, treaties, protocols, declarations.

And regrettably, to too few history sources.

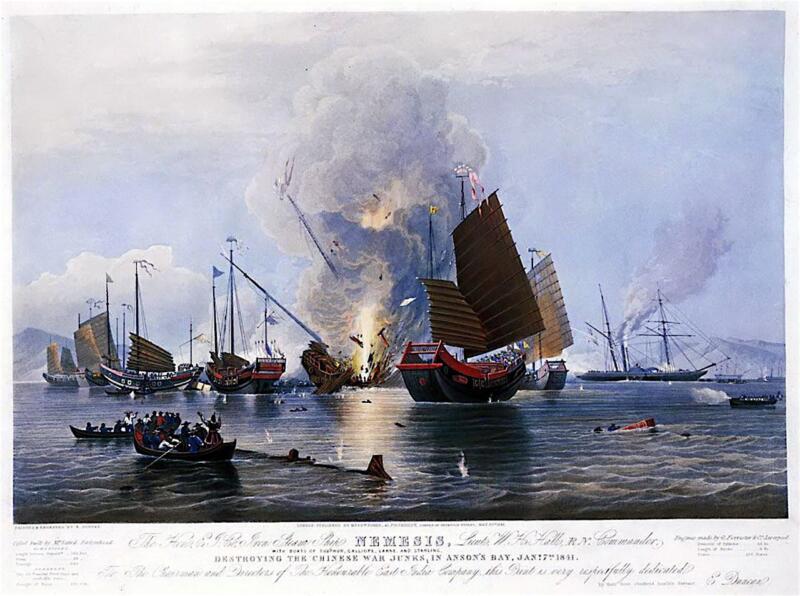

That absence is immediately evident. An early section titled “Human Rights in Historical Context” purports to lay out the background to China’s approach towards rights. Surprisingly, Potter neglects to mention the mid-19th century Opium Wars, in which Britain fought and defeated China in order to make the Qing government allow British opium to saturate the country. To fail to grasp how this forged China’s outlook on rights would be akin to not acknowledging the importance of the US War of Independence, its Declaration of Independence and its Bill of Rights in shaping the US perspective on rights.

One of the prizes of Britain’s Opium Wars victories was Hong Kong, and, as a price of regaining it in 1997, China had to accept Britain’s terms about Hong Kong’s political system. Imagine Britain, having lost the Channel Islands to Germany in the Second World War, accepting a Nazi-designed government there as a condition of their return to the UK. In contrast to the present Western clamour for democracy in Hong Kong, for well over a century the colony was run by a highly autocratic governor appointed by London. Only late in the day, as a return to China loomed, did Britain introduce multi-party democracy – in part to inflict on Beijing a persistent political irritant. A quarter century later, the tensions there are still festering.

As a result of the Opium Wars other European imperialist states imposed their own conditions on China. What came to be called the Unequal Treaties allowed Europeans to float through the Middle Kingdom enthroned on a palanquin of rights constructed in their own countries, meantime treating Chinese as rightless subordinates. Is it any wonder that China learned from this shame that, in a world dominated by imperialism, human rights are indefensible without a viable unified state? Neither Confucian nor communist — contrary to Potter — China’s insistence on national sovereignty as a foundation for rights is consistent with international norms going back to the 17th century.

Potter’s weak historical grounding — and maybe open bias — is also evident when he contrasts China’s BRI with the US Marshall Plan initiative that saw the US pump billions of dollars into Europe to stave off post-war economic collapse and the attendant emboldening of left-wing politics. To Potter, BRI “supports China’s human rights orthodoxy” that’s based on loyalty to the Communist Party and the primacy of political stability in development (p. 98). In Central Asia, “BRI enables China to reinforce commonalities of interest around social controls with authoritarian governments in developing economies” (p. 101).

By contrast, he writes, the Marshall Plan and other “US Cold-War-related development initiatives” were “grounded in open-market principles.” (p. 98) One would assume that these “open-market principles” include people’s democratic right to choose their own government. But the Marshall Plan was explicitly formulated to prevent communist gains in elections in France and Italy in 1946-8. The Italian Communist Party, for instance, was expected to win the April 1948 election to establish the first post-war government. To forestall that democratic transformation, the US declared that it would deny Marshall Plan aid to any country with a communist government. Washington gold was funnelled to right-wing political parties. A barrage of propaganda was directed at the Italian people. One small part of this effort was codenamed “Operation Bambi.” It produced anti-communist puppet shows to reach an illiterate public through their children. Italians obeyed their puppets and elected a right-wing Christian Democratic-led coalition. Fixing elections with injections of cash became a staple of US Cold War policy. When that didn’t work, the CIA and the US military stepped in – with the people of Greece, Iran, Guatemala, Indonesia, Brazil, Chile, among other countries, suffering the cost.

The same skewed approach towards human rights and lack of historical context is seen in Potter’s discussion of Canada’s detention of Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou in 2018. The three-year standoff, writes Potter, illustrated China’s “limited commitment to human rights and the rule of law” (p. 111). China retaliated to Meng’s arrest by imprisoning Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in a clear perversion of human rights standards. But to see only the two Canadians as hostages, the common phrase repeated over and over in Canada, is to fail to recognize Meng as a hostage, in violation of her human rights.

Potter sets out the background very superficially, explaining only that Canada acted “in deference to an extradition treaty request from the United States” (p. 111). This dodges the necessary articulation of the perversion of international law that lay beneath the US government’s pressure on Canada.

The United Nations Charter authorizes only the Security Council to determine if a state is a threat to the security of its neighbours or the world and to decide how to deal with that threat, including applying measures ranging from economic and diplomatic sanctions up to military quarantine or even invasion. So, when Iran and the five permanent Security Council members plus Germany reached a comprehensive nuclear deal in 2015, the Security Council ratified it and lifted UN sanctions on Iran.

But in 2018 US President Donald Trump unilaterally scrapped the deal and reimposed economic sanctions. The Trump administration’s action was illegal under international law. In doing so, the US employed one of its most potent international weapons — economic blockades. For all its multi-billion-dollar annual budget, the US military has been beaten by dedicated anti-imperialists. But US economic power still is formidable and, as in the case of sanctions against Iraq in the 1990s, has the capacity to kill hundreds of thousands of people and punish entire countries.

Less than a month after the US reimposed sanctions on Iran, in a clearly-coordinated move, the government of Canada arrested Meng in Vancouver. The fact that Canada itself doesn’t — and shouldn’t — abide by the illegal sanctions didn’t prevent Meng’s arrest. Meng was a bird in a gilded cage, enjoying conditions that would be envied by millions, but she was a hostage nonetheless.

Alongside its military confrontation of China, the Western mobilization of the human rights campaign against China will only grow. In June 2021, the US Senate approved the US Innovation and Competition Act that, in the words of Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Menendez, “will allow our nation to truly confront the challenges China poses to our national and economic security.” Incorporated into the act is a $300 million per year, four-year “Countering Chinese Influence Fund.” Its purpose is “to investigate and possibly sanction individuals, businesses, civic groups, educational institutions, and governments in foreign countries that have economic, social, cultural or family ties to China.” The Union of Concerned Scientists in the US has argued that the program could “make it appear, both to China and other nations, that Congress is seeking to weaponize human rights issues to win an economic and geopolitical contest and is unlikely to help human rights victims.”

It’s clear that China is not alone in “exporting virtue” on the subject of human rights. In fact, since the administration of Jimmy Carter adopted human rights as a foreign policy instrument in the late 1970s, the US has made human rights one of its most important appliances sold abroad, right up there with weapons and superhero films. Short of a World Trade Organization embargo on the dumping of human rights bumpf, a profound grasp of human rights history and principles is citizens’ best defence. We can add Pitman B. Potter’s Exporting Virtue? to our reading list on the subject, with the caveat that it’s a source to be read critically.

*

Larry Hannant thrills to the hunt for history in the everyday, suspects that the only route to the conquest of Berlin is over the Stolperstein Pass, subscribes to Vincent Scully’s warning that “Everything in the past is always waiting, waiting to detonate.” He’s the author of All My Politics Are Poetry (Victoria: Yalla Press, 2019, reviewed here by Natalie Lang). Forthcoming is an edited collection titled Bucking Conservatism: Alternative Stories of Alberta in the 1960s and 1970s (Athabasca University Press, 2021). Hannant taught aspects of human rights history for years at BC universities and colleges and is engaged in writing an anti-imperialist history of human rights. Editor’s note: Larry Hannant has also reviewed books by Suchetana Chattopadhyay, Eve Lazarus, Christabelle Sethna & Steve Hewitt, Kate Bird and Serge Alternês & Alec Wainman for The Ormsby Review, as well as an essay, I’m not your man: Norman Bethune & women.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1257 China’s human rights orthodoxies”