1236 Time tunnel to Vanderhoof

Mennonite Valley Girl: A Wayward Coming of Age

by Carla Funk

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2021

$32.95 / 9781771645157

Reviewed by Dora Dueck

*

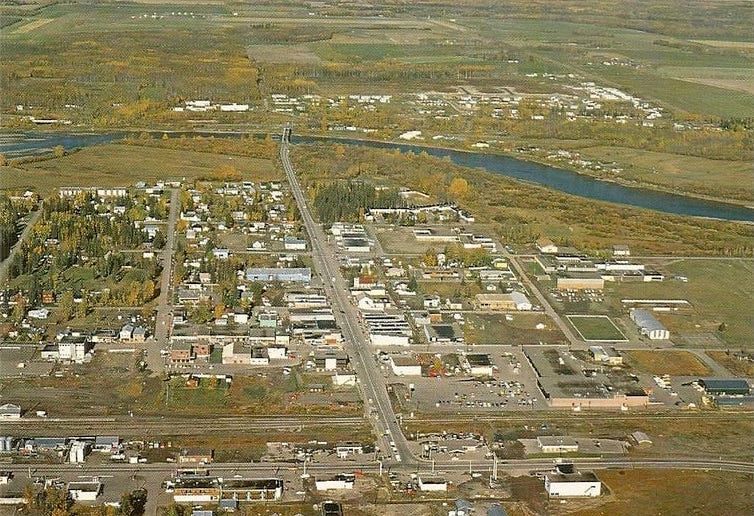

When Carla Funk was young, her northern hometown of Vanderhoof, British Columbia, was a place of delight. It might be small but it was beautiful, set into a lovely valley alongside the Nechako River. Her people were Mennonites who had settled in the area, her father originating in a group from Saskatchewan, her mother in an Amish-Mennonite group with U.S. origins. Funk chronicled the place and her childhood in the memoir Every Little Scrap and Wonder: A Small-Town Childhood (Greystone Books, 2019 — reviewed here by Candace Fertile), which was a finalist for the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize.

When Carla Funk was young, her northern hometown of Vanderhoof, British Columbia, was a place of delight. It might be small but it was beautiful, set into a lovely valley alongside the Nechako River. Her people were Mennonites who had settled in the area, her father originating in a group from Saskatchewan, her mother in an Amish-Mennonite group with U.S. origins. Funk chronicled the place and her childhood in the memoir Every Little Scrap and Wonder: A Small-Town Childhood (Greystone Books, 2019 — reviewed here by Candace Fertile), which was a finalist for the City of Victoria Butler Book Prize.

Now, in Mennonite Valley Girl: A Wayward Coming of Age, Carla Funk takes her story forward, into adolescence and through her teens in the late 1980s. As she changes, so, it seems, does Vanderhoof. “When I was a child, the whole earth was filled with glory…. But as the body grows up farther from the ground, so the shadow lengthens. Wonder, with its soft underbelly, retreats.” As teenagers will do, she begins to cast a critical eye on her people and town, to struggle with parental and community constraints, to stretch — though sometimes uneasily — within her developing body and desires, to yearn for a bigger and different world beyond her own. Reflecting on this stage, “valley” as a familiar and safe geographical location becomes a metaphor for shadow and shift, a metaphor underlined by Bible verses at section heads like “Why do you boast in the valleys…O backsliding daughter?” and “Every valley shall be lifted up.”

Funk’s memories unfold roughly chronologically, but the narrative is thematic rather than plot-oriented in structure. An early chapter deals with family dynamics, including differences between her mother’s and father’s side — smoking, for example, a “sanctioned sin” in his and one of the “forbidden vices” in hers. The death of Grandpa Funk raises the question of how Grandma could have loved this man “who only seemed to smile when someone else was crying,” a man so “stingy” he insisted that two squares of tissue were enough for wiping after using the toilet — if one learned to fold them properly! She writes of her relationship with her name, with fire, with driving. Her body provokes ongoing angst and scrutiny, as in recollections of her first bra, a makeover, and dieting. The chapter, “Small Town Limits,” in which Carla and friend Sindee wander about town, brilliantly captures the utter boredom, hidden fears, and innate silliness of adolescence in a place “growing smaller by the year.”

As in her previous book, Funk is wonderfully detailed and descriptive (“the blue-grey bruise of twilight” just one lovely example) in the stories she tells. She is often wry and humorous, but also honest about shadow she discovers, not only in others like her father, but within herself. During a week at camp, the “badness” of a girl named Gina in tight jeans and red high-heeled shoes first makes “the gleam of [Carla’s] own goodness brighten,” then disconcerts it by provoking jealousy. She glimpses “the junk that smouldered in my head and heart.”

Carla Funk is also the author of five books of poetry and the inaugural poet laureate of the City of Victoria. I was curious, as I read this memoir, whether her bent towards poetry began in her teen years. Indeed, there are inklings. While typing news stories for the local paper, she finds herself hungry for “a narrative with more excitement that what I believed my small town could hold.” In imitation of writers like Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, whom she learned about from an English teacher, she begins to keep a journal. Unsure how to make a poem, however, she writes daily letters instead — to her “dream dad,” Bill Cosby.

Reference to Miriam Toews’ work in a discussion of Carla Funk’s memoir may be inevitable, for both are of Mennonite background and grew up in the claustrophobia of a small, relatively closed religious community, under a Mennonite history “burnished to near-mythology.” Their voices are quite different, however. Funk’s writing reads softer and more poetic against Toews’ unique rush of comedy and sorrow. This is not a critique, simply comparison, for I admire both. In reading Mennonite Valley Girl, I was actually reminded of American poet Tracey K. Smith’s memoir Ordinary Light, which I read some years ago. Like Smith, who also grew up in a religious home, Carla Funk mines her youthful memories for meaning and emotional resonance in such a way that what remains is as fully realized as what’s discarded.

The waywardness projected in the memoir’s subtitle never seems that extreme, in fact, except for the way life itself feels extreme and fraught within the changing mind and body of a teen. There’s the push against parental strictures, to be sure, phone pranks, self-conscious smoking and romance fantasies and dancing, even though “[d]ancing was something done by other people,” not Mennonites. In the boredom chapter mentioned above, she notes, “As much as Sindee and I liked the idea of being bad, we remained girls in oversized sweatshirts and pleated chambray shorts, replicas of the Junior Miss section of the Sears catalogue.” We discover — though she’s humble about it — that this girl is an achiever, not only a whiz typist but also high school valedictorian. In her Vanderhoof context, the most wayward thing about Carla Funk’s youth may have been her determination to leave. And, by the end of this fine book, she’s set to do just that.

*

Dora Dueck is the award-winning author of four books of fiction, most recently All That Belongs (Turnstone Press, 2019 — reviewed here by Valerie Green), as well as stories and essays in a variety of journals and anthologies. Her novel This Hidden Thing won the McNally Robinson Book of the Year award in Manitoba in 2011 and her collection of short stories, What You Get at Home, won the High Plains Award for short fiction in 2013. She is also a winner of The Malahat Review’s 2014 novella contest. After some four decades in Winnipeg she currently lives in Tsawwassen. Visit her blog here.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1236 Time tunnel to Vanderhoof”

What a lovely and sensitive review, Dora. I always look forward to reading what you write, even when it’s about someone else’s writing. This piece makes me want to read the book. Think I will!

Thanks, Dora. I had not heard of this writer before. Excellent review!