1234 A matter of thwarted desire

My Two-Faced Luck

by Brett Josef Grubisic

Surrey: Now or Never Publishing, 2021

$19.95 / 9781989689271

Reviewed by Geoffrey D. Morrison

*

In My Two-Faced Luck, Brett Josef Grubisic concludes his River Bend Trilogy with a novel that movingly fulfills the promise of its unique and ambitious premise. As with the other River Bend books, My Two-Faced Luck takes place in part in the fictional River Bend City, a Mission, BC of the imagination – this time at the city’s Horsetail Institute, analogous to the real-world minimum-security prison at Ferndale. It is here, in 1990, that an unnamed American inmate records the story of his life onto a series of audiotapes. He is serving time for the 1985 murder of a rich widow on a cruise ship that just happened to be moored in Victoria on the day in question, and the autobiographical act has a special urgency for him because he is dying of liver cancer. The inmate is a gay man who was born into a poor, abusive family in West Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1927, and he has lived his life straining against the limitations set by these starting conditions in the ways he knows best.

In My Two-Faced Luck, Brett Josef Grubisic concludes his River Bend Trilogy with a novel that movingly fulfills the promise of its unique and ambitious premise. As with the other River Bend books, My Two-Faced Luck takes place in part in the fictional River Bend City, a Mission, BC of the imagination – this time at the city’s Horsetail Institute, analogous to the real-world minimum-security prison at Ferndale. It is here, in 1990, that an unnamed American inmate records the story of his life onto a series of audiotapes. He is serving time for the 1985 murder of a rich widow on a cruise ship that just happened to be moored in Victoria on the day in question, and the autobiographical act has a special urgency for him because he is dying of liver cancer. The inmate is a gay man who was born into a poor, abusive family in West Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1927, and he has lived his life straining against the limitations set by these starting conditions in the ways he knows best.

The story has a basis in fact; it fictionalizes the life of Robert Frisbee, who likewise died in Mission serving a murder sentence. As we learn from the Acknowledgements page of the book, Grubisic first learned about Frisbee in Murderers’ Row: An International Murderers’ Who’s Who, by Robin Odell and Wilfred Gregg. The authors identify him simply as a “fifty-nine-year-old homosexual found guilty of murdering an elderly widow at sea on a cruise ship.” As Grubisic puts it, “Frisbee’s status as homosexual had apparently made an impression on Odell and Gregg. For me, the man’s mysterious decades of queer daily history inspired speculation far more than the murder ever would.” With this context in mind, Grubisic’s reclamation of the full sweep of Frisbee’s life makes it a thoughtful and very welcome intervention into the crime genre at a moment when the “true crime story” has come to lose its way. As the writer Anna Fitzpatrick recently expressed it, “I’m thinking about how much of the current True Crime boom was spurred by projects like serial and Making a Murderer that were, however messily, about flaws in criminal justice system, and how quickly that curdled into podcasts about how scary murderers are everywhere.”

Unlike true crime’s curdled progeny, Grubisic is not interested in lingering on sensational crime-scene details or cheering for the police. The real Frisbee, who at the time was mixing sedatives and alcohol, claimed not to remember the murder, and the fatal act is likewise a black box for the fictional inmate. The book presents a Canadian criminal justice system more than happy to make the trial a referendum on the inmate’s character as a gay man and alleged “gold digger,” and the Crown Prosecutor quite successfully appeals to the homophobia and class prejudices of the jury. That said, neither the murder nor the trial are the true focus of the book. Grubisic is instead interested in the terms of a queer life lived in the face of incredible obstacles, the acute formulations and re-formulations of that life at its end, and, most affectingly of all I think, the transmission of this buried queer history to the present.

This latter goal is accomplished by a highly effective device. Before we meet the inmate, we meet Seerat Gill, a former nurse in the infirmary at Horsetail. She attends to the inmate on several occasions in 1990 and enjoys their conversations, but is nevertheless surprised to inherit “a jumble of cassette tapes in a plastic bag” after he dies. Gill is herself a queer woman, but it’s not clear — and I think it’s the right choice that it’s not clear — whether they discussed her sexuality openly, or under what circumstances she earned his trust. Regardless, he trusts her, and it is to her that he addresses the story of his life.

It all feels so tenuous, the channelling of this voice from the past, and this is part of what makes the framing device of the book so moving. Gill never even knows whom the inmate told to give her the tapes; they just appear one day with a note that says “To Seerat’s office.” At the time she receives them she is young, sure of things, and not ready to hear his story. It takes her divorce in 2020 and the period of quiet reflection that follows for Seerat to finally turn to the tapes, transcribe them, and send them to a publisher. She later speculates how she would have felt if she had listened to the tapes back in 1990 with her then-girlfriend, later ex-wife, guessing that:

We’d have judged the episodes as a cautionary tale and patted ourselves on the back for having moved so far beyond shame, secrecy, and victimhood. And we’d have been thankful for being born after the bad old days, when struggle was a forgone conclusion and heavy drinking appeared to be a direct avenue to escape the self-hatred caused by virulent, unimaginably widespread homophobia.

Instead, listening in 2020 with less prejudgment, she finds the tapes an object lesson in “the sheer unknowability of another person.”

With this frame in play, Grubisic masterfully guides and subverts expectations, as inexorably the book dispels any readerly impulse either to self-congratulation or to pity for its protagonist. You may feel an initial desire to lament that he was born too soon, in the wrong place, or to the wrong family or social class to live a picture-perfect gay life, but to do so is to miss the point. The inmate is not self-pitying, not really, and he does not ask us to pity him. He simply wants us to understand. I am reminded of another attempt to reconstruct a contentious life from the testimony of found tapes: Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man, a work a friend once called “empathy in film form.” It’s with the same kind of patience and imagination that Grubisic proceeds in My Two-Faced Luck.

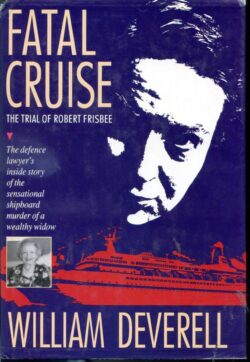

Another key to the book’s success is Grubisic’s reconstruction of the inmate’s speaking voice. In the Acknowledgments he cites BC lawyer and crime writer William Deverell’s Fatal Cruise: The Trial of Robert Frisbee as an important source. Deverell was Frisbee’s lawyer and the interviews and correspondence he includes in his book provide a sense of the man’s vocal delivery. For instance, in Deverell we get the following remark from an interview with Frisbee: “Mother was so very, um, non-educated about sex. I think she married a man that was very aggressive and, uh, adventuresome.”

These ghost traces as transcribed by Deverell — presumably also from tapes? — are a primary source that Grubisic builds out into a living narrative presence. We hear the hesitation, the euphemisms, even the “ums.” It’s an impressive feat, and the result is a convincing depiction of a man with a very particular life history trying to make sense of it as it comes to a close. The inmate repeats himself, but in a way that makes sense — he rotates certain themes in his mind, returns to them, picks at sore spots, tries for a resolution. He especially dwells on the possibility of having done things differently, and on his family.

The inmate’s voice also interestingly subverts another crime fiction form — that of the noir narrator. As Mike Davis eloquently shows in City of Quartz, the classic Depression-era noir fictions were an expression of the anxiety of California’s downwardly mobile middle classes in the 1930s. In his words, “Noir was like a transformational grammar turning each charming ingredient of the boosters’ Arcadia [i.e., the sunny California of the 20s real-estate boom] into a sinister equivalent.” Noir as a “transformational grammar” turning the charming into the sinister seems baked into its very style. The noir heroes, and in particular those of Hammet and Chandler, speak in a language that draws from and arrestingly modulates the common storehouse of American expression — stock phrases, mixed metaphors, similes — all of this tersely compressed by characters who do not have much time (Hammet bigger of course on the compression, Chandler on the metaphor, their stylistic inheritors borrowing more or less from one or the other).

The inmate is also running out of time, and like them he draws on the shared repertoire of mid-century phrases as he charts a Depression-era childhood and Eisenhower-era adulthood of immense grief and trauma. There is charm and there is pain, sometimes the one intimately nestled on top of the other. Unlike the noir heroes, though, the inmate’s family is too poor to have fallen in the Depression — they were down already. And unlike the noir villains, in Davis’s words “déclassés or idle rich” who, in their quest for the inheritance money, “invariably choose murder over toil,” the inmate is something more complex. Working variously as typist, assistant to a crook, chauffeur, and valet, he is a white-collar proletarian of the servant class, grasping for whatever momentary relief he can find.

Crucially, as a queer man growing up either side of the Second World War, he stands apart from the performatively, almost cartoonishly straight noir heroes. The inmate is a private eye in the quite literal sense that in the formative years of his life he cannot manifest his desires too publicly — the Cold War panic that queer people are an internal enemy liable to be blackmailed into spying for the Soviets constantly preys upon his mind. His noirish metaphors therefore work in a way his straight counterparts’ would not, drawing from cultural sources like the radio song, and in particular from the sentimental language of love ballads. Grubisic cites the California radio station KCEA-FM, which specializes in standards, swing, and big band, as an important influence on his development of the character’s point of view. These songs, which as the inmate puts it turn his “brain fiery with imaginings,” come to crystallize the transcendent desires he never manages to realize in life.

It’s on the matter of thwarted desire and missed chances that the book does some of its most careful and psychologically perceptive work. The hidden engine of the book, the source of its narrative power, is its empathic reconstruction of the wishes and regrets of a man whose choices seemed like a good idea at the time. You feel the essential boredom and repression and narrow horizons that would have killed him in some other way if he had merely stayed in West Springfield, stayed on as a typist, finished beauty school and done perms in a salon, stayed in the Daly City apartment – even his ultimately doomed codependent relationship with the rich elderly couple has its own melancholy logic once you know how this man thinks and feels. But on the other hand you wish he had stuck with Clarence, wish he had moved in with Nikos, wish he had been galvanized by the White Night Riots in the wake of the assassination of Harvey Milk instead of merely watching them on television … not because you think you know better but because he has become someone you care about. In its uncanny resurrection of this lost voice, My Two-Faced Luck stands as a great achievement.

*

Geoffrey D. Morrison is the author of the poetry chapbook Blood-Brain Barrier (Frog Hollow Press, 2019) and co-author, with Matthew Tomkinson, of the experimental short fiction collection Archaic Torso of Gumby (Gordon Hill Press, 2020). His work has appeared in Grain, PRISM, The Malahat Review, The Temz Review, Shrapnel, The Rusty Toque, and elsewhere. He was a finalist in both the poetry and fiction categories of the 2020 Malahat Review Open Season Awards and a nominee for the 2020 Journey Prize. He lives on unceded Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh territory.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

22 comments on “1234 A matter of thwarted desire”