1214 Loving and losing Louisa

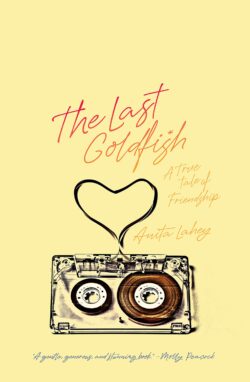

The Last Goldfish: A True Tale of Friendship

by Anita Lahey

Windsor, ON: Biblioasis, 2020

$22.95 / 9781771963435

Reviewed by Carol Matthews

*

Part bildungsroman and part meta-memoir, Anita Lacey’s The Last Goldfish; A True Tale of Friendship is an account of a young girl watching a beloved friend struggle with and ultimately succumb to cancer at a time when her life should have been just opening up. The story is a step-by-step account of a friendship related through daily events, flashbacks, journal notes, and medical reports about the progress of the cancer and the deepening of the bond between the two.

Part bildungsroman and part meta-memoir, Anita Lacey’s The Last Goldfish; A True Tale of Friendship is an account of a young girl watching a beloved friend struggle with and ultimately succumb to cancer at a time when her life should have been just opening up. The story is a step-by-step account of a friendship related through daily events, flashbacks, journal notes, and medical reports about the progress of the cancer and the deepening of the bond between the two.

Written over a twenty-five-year period, Lahey experimented with different ways of telling her story but finally, as she said in an interview with her publisher, she realized that this tale of friendship was as much about her as about her friend and she “only aimed to be as true to the story as I possibly could be.” She is successful in this aim: the everyday events of the girls’ friendship from the start of Grade Nine through to Louisa’s death when they were twenty-two years old. The notes they slip back and forth in class, the poems they record in their journals, their applications to university, their conversations about boys and sex, their hopes, their anxieties and Louisa’s worsening illness: all of it rings true.

It’s easy to understand Lahey’s devotion to her friend. A force of nature, Louisa embodies their motto of Carpe Diem, the message which is written on a sheet of paper she drops onto Lahey’s lap when the two of them decide to tackle the school board about its final exam policy. From their first meeting, Louisa radiates energy with her thick red hair that was “like an explosion in a comic script,” and her blue eyes, which were “not the usual sky blue: deep and rich, like new jeans right out of the wash.”

In episodes that take place over the next several years we witness Louisa’s weight loss, the appearance of new “bumps” in various parts of her body, the changes in her face, her sunken cheeks, and the loss of her hair. Towards the end, her face becomes translucent and her cheekbones become “delicate sculptures” with her eyes floating above “like planets on a mobile.” The ghastly progression of this illness is reported clearly and without sentimentality, and the effect is devastating.

Lahey is an award-winning poet, a journalist, and a writer of essays. As a poet, she is known for metaphor, imagery, and sharp descriptions. In The Last Goldfish, we see both her poetic talent and her journalistic skill at work. In one hospital scene, she describes taking the elevator down to the hospital basement while trying not to read the directional signs to the morgue as they head to “vending-machine heaven” in a “low-ceilinged cavernous room lit with fluorescent lights” and a range of machines that contain carousels filled with yogurt cups, lone apples and oranges, plastic-wrapped carrot sticks, granola bars, and so forth. Lacey captures the depressingly mundane details of the setting but also sees it tragically, as “an Edward Hopper painting, black and overlit, filled with sad faces and unsatisfied hunger.”

There are short periods between Louisa’s treatments that seem briefly hopeful but these are interrupted with the re-appearance of new cysts. The cancer comes and goes like another character in the chronicle, and each appearance is followed by new forms of tests and treatment: pills, ultrasounds, CAT scans, yoga programs, a cancer support centre, visualization instructions, and chemotherapy. There’s also Levamisole, an immunomodulator that sounds like “a piece of machinery equipped with knobs and controls, by which you could reset your whole immune system. Like any improbable invention, it was imperfect, even dangerous.”

The young Lahey tries to assess the situation from day to day, wondering about what the cancer was but then concluding that she and her friend have “things to do, people to see.” She arranges outings and activities until Louisa decides to move to Vancouver to be with her boyfriend. They maintain contact through telephone conversations but soon Louisa calls in a voice that “seemed almost entirely devoid of herself” and reports that she has tumours in her throat. She asks her friend if she could come to visit, and of course she does.

The title of the story refers to an anecdote of an early school science experiment that required Lahey and another girl to compare how well goldfish survived in different settings. At the end of the book, three goldfish are left in Louisa’s care and two of the fish die. Lahey ends up with the last goldfish but can’t remember how long it survived: “at some point it swims right out of my memory.” She wonders whether Louisa might have thought the fish was cute, but of course she can’t ask. Lahey is “frustrated or saddened, occasionally outraged, by the eternity tied to that can’t.”

The story loops about in time. Louisa does not swim away but we, following Lahey’s memories, swim around and through her memories, piecing together a story of the years during which the girls grew up together. At the end of the book, the narrative returns to the scene at the start of the beginning and Lahey’s first meeting with Louisa in her Grade Nine French class. Now, at mid-life, the author recalls her early clarity about the difference between passé composé and imperfait but she questions the finality of passé composé. “Grammar,” she says, “fails to account for memory and its workings, for the continual overlay of plotlines and half-written stories in the most modest of lives.”

Every loss is unique and each bereavement has its own story. The story here is of a remarkable friendship that tracks a painful illness and a premature death while still maintaining exuberance, hope, humour, and love. How lucky Anita was to have such a friend. How lucky we all are that Anita Lacey has told the story of it.

*

Carol Matthews has worked as a social worker, as Executive Director of Nanaimo Family Life, and as instructor and Dean of Human Services and Community Education at Malaspina University-College, now Vancouver Island University (VIU). She has published a collection of short stories (Incidental Music, from Oolichan Books) and four works of non-fiction. Her short stories and reviews have appeared in literary journals such as Room, The New Quarterly, Grain, Prism, Malahat Review, and Event. Editor’s note: Carol Matthews has also reviewed books by Ivan Coyote and Tamara Macpherson Vukusic for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1214 Loving and losing Louisa”