1179 History galleries & robber barons

The Object’s the Thing: The Writings of Yorke Edwards, A Pioneer of Heritage Interpretation in Canada

by Richard Kool and Robert A. Cannings (editors)

Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum Press, 2021

$24.95 / 9780772678515

*

Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures

by Moira Dann, with an afterword by Bruce Davies

Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2021

$20.00 / 9781771513487

Both books reviewed by Forrest Pass

*

“Almost everyone who has visited a Canadian park or museum has been touched by [R. Yorke] Edwards’ legacy — but few know his name,” observes the cover blurb of The Object’s the Thing. I had never heard of Edwards before agreeing to review this collection of his writings. This is a bashful admission, as I am not only a museum curator by profession but also a proud “Jerry’s Rangers” alumnus, having racked up (ahem) quite a collection of the paper moose antlers that B.C. Parks naturalists used to distribute to young attendees at interpretive programs. Edwards’ influence was as evident in my childhood introduction of natural history as it is in my daily work in adulthood: apparently I am a lifelong Yorke Edwards disciple and never knew it until now!

“Almost everyone who has visited a Canadian park or museum has been touched by [R. Yorke] Edwards’ legacy — but few know his name,” observes the cover blurb of The Object’s the Thing. I had never heard of Edwards before agreeing to review this collection of his writings. This is a bashful admission, as I am not only a museum curator by profession but also a proud “Jerry’s Rangers” alumnus, having racked up (ahem) quite a collection of the paper moose antlers that B.C. Parks naturalists used to distribute to young attendees at interpretive programs. Edwards’ influence was as evident in my childhood introduction of natural history as it is in my daily work in adulthood: apparently I am a lifelong Yorke Edwards disciple and never knew it until now!

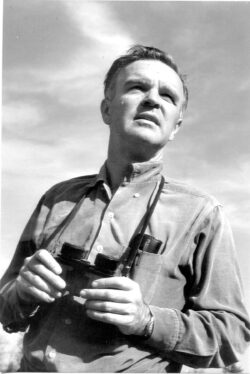

Richard Kool and Robert A. Cannings introduce their friend and colleague, who died in 2011, as an unsung pioneer of Canadian heritage interpretation. An avid naturalist from his boyhood in Toronto, Edwards studied forestry at the University of Toronto and zoology at UBC before joining the provincial parks service in 1951. There, on a shoe-string budget, he single-handedly created a natural history interpretation program focused on small “nature houses” and regular events such as naturalists’ presentations and guided walks. After a stint in Ontario with the Canadian Wildlife Service, Edwards returned to the West Coast, as assistant director and later director of the British Columbia Provincial Museum (BCPM), now the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM).

To make their case, Kool and Cannings have assembled a diverse sample of Edwards’ writings, from his first publication — a brief article on wood warblers that appeared when Edwards was still in high school — to two retrospective pieces on the early history of parks interpretation that he wrote in the 1980s, after he retired. The selection includes previously published articles, as well as rough speaking notes for conference keynotes and briefing documents for new park naturalists, complemented by an affectionate introduction and biography and an exhaustive bibliography.

The editors’ selection illustrates Edwards’ ongoing refinement of his interpretive philosophy. The evolution is subtle, and the selections sometimes seem a little repetitive, especially if you read the book chronologically. Nevertheless, taken as a whole, Edwards’ writings present a public intellectual tweaking his message for various audiences, and adapting his interpretive approach to new aspects of natural and human heritage.

Over the years, Edwards’ focus shifted from interpreting “untouched” wilderness in provincial parks to making sense of human interactions with the natural world to shaping the experiences of museum visitors. Yet his fundamental interpretive principles remained remarkably constant. He believed that public interpretation must be grounded in scientific accuracy, but he disliked overly intellectual presentations, which he felt put off visitors. At the other extreme, and writing in the shadow of Montreal’s Expo ‘67, he distrusted “Expomania,” a pandering over-reliance on design and interactive technology that, Edwards argued, isolated visitors from the subject at hand. The unadorned enthusiasm of a passionate interpreter should be enough to excite visitors about natural and human history.

Central to Edwards’ interpretive approach was contact between a curious public and real objects, whether natural specimens or historical artifacts. In his view, objects are best interpreted in their original context, a relatively straightforward task in a provincial park or nature reserve, but more difficult in a museum setting. At different points in his career, Edwards offered two different solutions to this challenge, establishing the terms for discussions that still animate curators and interpreters.

The first solution was to bring a version of the original context, or elements thereof, into the museum. In the 1960s, Edwards had predicted that the historical museums of the future would immerse visitors in recreated historical events and atmospheres. To some extent, this prediction came to pass. The Modern History Galleries at the BCPM, which opened in 1972, the same year that Edwards joined the museum as assistant director, epitomized a movement to large-scale reconstructed historical environments. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Canadian Museum of Civilization (CMC) would take the same immersive approach in the Canada Hall, developed under the curatorial direction of Daniel Gallacher, who had worked with Edwards at the BCPM.

Both the Modern History Galleries and the Canada Hall were compelling recreations, painstaking in their attention to detail. In Edwards’ terms, they were intended to make converts rather than experts, that is, to inspire wonder and pique curiosity rather than to convey detailed information. Countless smaller museums also applied the immersive approach, albeit on a smaller scale, reconstructing general storefronts, Victorian parlours, and turn-of-the-century schoolrooms to contextualize local relics of yesteryear.

Yet large-scale reconstructions were not exactly what Edwards had in mind. Some critics saw in them the “Disneyfication” of history — a latter-day version of the very Expomania that Edwards had cautioned against. Moreover, they often featured relatively few real artifacts, and those that were original were not always easy to distinguish from the reproductions. Both the RBCM and the CMC changed course in the 2000s, the former opening its complementary Century Gallery to showcase more of its modern history collections and the latter, now renamed the Canadian Museum of History, developing an entirely new permanent history exhibition in which artifact authenticity was a guiding interpretive principle.

Edwards, it appears, appreciated the challenges of bringing outside environments into the museum, and late in his career, in the title piece of the collection, he offered an alternative strategy. In addition to presenting an object’s historical or ecological context (which he styled the “object-out” approach), interpreters should consider its intrinsic qualities and the story that the object itself can tell of its structure, function, and use (the “object-in”). Just as museologists have debated and continue to debate the merits of simulated immersion versus a focus on authentic objects, which Edwards hinted at half a century ago, curators continue to try to strike the balance that Edwards suggested between object as illustration and object as storyteller in its own right.

Yorke Edwards’ legacy, then, runs deep in Canadian scientific and historical interpretation, especially in his adoptive province. The most intriguing work in Kool and Cannings’ edition is a 1962 compilation of British Columbia-based “Interpretation Ideas,” written by Edwards and whimsically illustrated by young naturalist Raymond Barnes. It is remarkable how many of these ideas have come to fruition, from working urban farms to teach children about food production to a migratory bird sanctuary on the Fraser River delta and a Cariboo cowboy museum.

And Edwards’ writings reveal other tantalizing ideas, decades ahead of their time, that we can only wish he had explored further. In the same conference presentation in which he called for immersive historical recreations, Edwards proposed that “the important history is really historical human ecology,” hinting that interpreters should meld natural and human history. Was Edwards an early proponent of the Anthropocene? Alas, there is no article in The Object’s the Thing that elaborates this idea, though the book’s comprehensive bibliography of Edwardsiana does list a 1992 article on “Environmental Museums.” I await the launch of the book’s promised companion website, the Edwards-Ritcey Online Library, to find out if this pioneer of heritage interpretation was also a prophet of public environmental history.

*

House museums and living history sites come closest to Yorke Edwards’ ideal of “historical interpretation where you almost become part of historical events,” or at least learn about those events where they took place. Like me, Moira Dann appears to be a (perhaps equally unwitting) Edwards disciple. In the preface to Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures, she describes the sympathetic understanding of the past and its people that a well-curated and well-interpreted house museum can inspire in staff and visitors alike. And Dann’s justification for focusing on a relatively small selection of objects is decidedly Edwardsian. In a 1962 briefing to provincial parks interpreters, Edwards warned that “the greatest danger is perhaps in overlooking the simple things;” visitors might never have considered the crystalline structure of a pebble, or the intricate veins of a leaf. For her part, Dann, quoting James Joyce, offers that “in the particular is contained the universal.” Close consideration of particular artifacts, including several that visitors might overlook, is an entry point into the rich history of a favourite Victoria attraction.

House museums and living history sites come closest to Yorke Edwards’ ideal of “historical interpretation where you almost become part of historical events,” or at least learn about those events where they took place. Like me, Moira Dann appears to be a (perhaps equally unwitting) Edwards disciple. In the preface to Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures, she describes the sympathetic understanding of the past and its people that a well-curated and well-interpreted house museum can inspire in staff and visitors alike. And Dann’s justification for focusing on a relatively small selection of objects is decidedly Edwardsian. In a 1962 briefing to provincial parks interpreters, Edwards warned that “the greatest danger is perhaps in overlooking the simple things;” visitors might never have considered the crystalline structure of a pebble, or the intricate veins of a leaf. For her part, Dann, quoting James Joyce, offers that “in the particular is contained the universal.” Close consideration of particular artifacts, including several that visitors might overlook, is an entry point into the rich history of a favourite Victoria attraction.

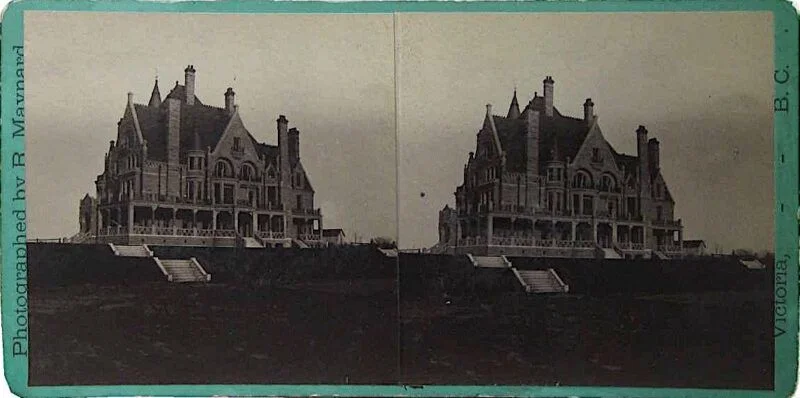

Mind you, few of the treasures that Dann has selected qualify as truly “simple.” After all, Craigdarroch Castle’s original residents were local gentry. Robert Dunsmuir, who built the castle in the late 1880s and died before it was completed, was a ruthless timber, coal, and railway magnate; his widow, Joan, and children were pillars of Victoria society, and the eldest scion, James, served as both premier and lieutenant-governor. Elaborate clocks, sculptures, stained glass windows, oil paintings, and dining room sets illustrate the family’s taste for high Victorian and Edwardian decorative arts.

For the most part, Dann’s interpretation of the Castle’s treasures follows Edwards’ “object-out” pattern: the object introduces an aspect of Dunsmuir and Craigdarroch history, which Dann recounts imaginatively and enthusiastically. Although Dann provides at least some provenance for many of the objects, only a few get the full “object-in” treatment. The quest to track down the artist who produced the castle’s exquisite stained glass windows is a fascinating example of curatorial detective work. A brief account of the castle’s Goodwin and Jordan piano hints at an as-yet untold larger story of a short-lived Victoria firm.

A pattern emerges among those treasures for which provenance is available. Apart from the Goodwin and Jordan piano and some items produced by the Dunsmuirs themselves, the family’s treasures originated far from the city and province where they are now exhibited. No stained glass window or oil painting depicts a British Columbia setting, though the family apparently admired California landscapes. The family heirlooms include neither First Nations curios nor zoological trophies, and an ivory tatting shuttle is the only soupçon of chic chinoiserie.

This is not a criticism of Dann’s selection; she is certainly well aware of the Dunsmuirs’ Victoria and British Columbia contributions and connections. Rather, it is a key message of the Dunsmuirs’ material legacy. Here was a family whose style, like that of fellow robber barons in New York or Montreal, was deliberately, and near-exclusively, European. The house itself, a Scotch baronial castle transplanted to Vancouver Island, insulated its inhabitants from the colonial realities outside — realities that were the source of their prosperity.

What is true of Craigdarroch Castle is true, to varying degrees, of many house museums: class as well as chronology separate most visitors from these houses’ long-dead occupants, and this foreignness is part of their appeal. A house museum presenting the experience of an urban working family would be a project worthy of Yorke Edwards’ “Interpretation Ideas:” the life stories of the 99 percent have typically fared better in immersive museum exhibits and in rural heritage villages. Yet Dann’s inclusion of a housemaid’s radiator brushes and the Castle’s speaking tubes (an early intercom system for summoning the servants) among her treasures selection illustrates how even elite house museums can present stories and perspectives that the houses’ original owners might not have deemed worthy to share, or might not even have considered.

The fate of the house and its collection after the Dunsmuirs is another unexpected history that Dann highlights throughout the book. Unlike those house museums that were bequeathed to their non-profit or municipal custodians fully furnished, Craigdarroch Castle was emptied in 1909, its treasures sold to the highest bidder. Luckily, many items stayed close by, but the Craigdarroch Castle Historical Museum Society has had to invest considerable money and effort to reacquire them; as Craigdarroch curator Bruce Davies explains in the afterword to Dann’s book, reacquisition rather than reproduction has been his guiding principle.

In addition to interpreting these reunited objects in their original context, Dann (and the Society) also interpret the place itself, for structural elements of the Castle itself speak to its post-Dunsmuir history. These include plumbing fixtures from the building’s time as a convalescent hospital for shell-shocked Great War veterans and student graffiti, including the signature of a famous Canadian historian, scratched into a mantelpiece when the castle housed Victoria College. This is “object-in” in a big way!

Craigdarroch Castle in 21 Treasures demonstrates the power of an object to tell multiple stories. Dann’s enthusiasm for the Castle’s treasures and her gift for imagining and evoking the lives of the people who first treasured them make this book an attractive souvenir for those who know Craigdarroch Castle well and an encouragement for those who have not yet visited.

I think Yorke Edwards would approve, too.

*

Forrest Pass is a curator in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division at Library and Archives Canada. In previous roles, he has curated a portion of the Canadian Museum of History’s Canadian History Hall (successor to the Canada Hall) and temporary exhibitions at two Ottawa house museums, the Billings Estate National Historic Site and Pinhey’s Point Historic Site. Originally from the Sunshine Coast, he fondly recalls his first encounters with Edwardsian nature interpretation at Monck Provincial Park and historical interpretation at Barkerville. Editor’s note: Forrest Pass has also reviewed books by Hannah Turner, Maddie Leach & Michael Kluckner, Philippe Tortell, Mark Turin, & Margot Young, and Tom Hawthorn for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1179 History galleries & robber barons”