1116 Politics on a punch card

Cataloguing Culture: Legacies of Colonialism in Museum Documentation

by Hannah Turner

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2020

$32.95 / 9780774863933

Reviewed by Forrest Pass

*

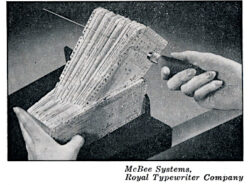

On the desk of my home office, I keep a relic of museum cataloguing in days gone by: a McBee Keysort manual punch, model 5201-630. Resembling a standard hole punch, this tool once produced triangular notches, about half a centimetre deep, along the edge of pre-printed, pre-perforated cards. The presence of a notch at a particular spot represented a binary value; an intact round perforation, its opposite. A dowel resembling a knitting needle, inserted through a deck of data cards at a given point, caught only those cards with intact perforations, excluding the notched cards. Repeating the process refined the search. The applications of this low-tech system — an intermediate stage between card catalogues and early computer databases — ranged from medical record keeping to folklore and linguistic studies to library and museum cataloguing.

On the desk of my home office, I keep a relic of museum cataloguing in days gone by: a McBee Keysort manual punch, model 5201-630. Resembling a standard hole punch, this tool once produced triangular notches, about half a centimetre deep, along the edge of pre-printed, pre-perforated cards. The presence of a notch at a particular spot represented a binary value; an intact round perforation, its opposite. A dowel resembling a knitting needle, inserted through a deck of data cards at a given point, caught only those cards with intact perforations, excluding the notched cards. Repeating the process refined the search. The applications of this low-tech system — an intermediate stage between card catalogues and early computer databases — ranged from medical record keeping to folklore and linguistic studies to library and museum cataloguing.

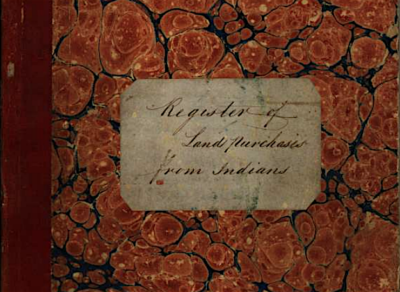

Hannah Turner’s Cataloguing Culture does not mention the McBee Keysort system by name, but punch-card technology is part of the story she tells. So are leather-bound accession registers, card catalogues in patinated oak cabinets, and whirring mainframe computers. The physical tools and bureaucratic procedures of cataloguing, Turner argues, have profoundly shaped understandings of Indigenous collections in colonial museums. Those collections themselves have received much scholarly attention over the past few decades, beginning with classics like Douglas Cole’s Captured Heritage (Douglas & McIntyre, 1985). Turner, by contrast, contributes to material culture studies by reconstructing the material culture of museology itself.

Before we delve much deeper, a word about audiences. “This is a book about specifics,” Turner writes in her introduction, “I am interested in little things.” As you, dear reader, may have gathered from the McBee Keysort manual punch anecdote above, this is a predilection that Turner and I share. Those who work in museums and memory institutions large and small may experience a thrill of recognition — as I did — at details of past and present collections practices that they may have encountered in their own institutions. The level of detail may be heavy for the casual browser, but intrigued general readers will find the book a fascinating initiation into museum arcana.

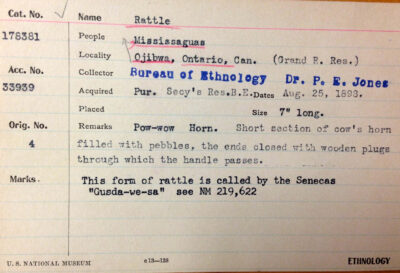

Arcana are not the same as trivia. In Turner’s story, the little things matter because they illustrate how museums transformed living objects into representative “specimens.” Her case study is the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Washington, D.C., but the pattern was broadly similar at other institutions established in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries. Taking their cues from colleagues in the natural sciences, many nineteenth-century ethnologists were most interested in the materials and basic function of Indigenous artifacts and less with narratives of daily use and cultural meaning. Their collecting and classification tools reflected these interests. A later generation reversed this focus, but typically had neither the time nor the inclination to recatalogue existing collections.

The colonial collection is Turner’s case study, and the choice is both timely and relevant, as museums large and small reflect on their role in colonial dispossession and work toward reconciliation with Indigenous communities. Yet her insights are not limited to Indigenous artifacts, nor will her work be of interest only to those who work with these collections. Early curators collecting settler material culture applied many of the same assumptions and biases as their ethnologist colleagues. They favoured artifacts that demonstrated an artisan’s skill over those that showed signs of everyday use. They sought out “pure” products of folk cultures and sometimes overlooked evidence of adaptation and hybridity, and their rigid classification systems left little room for nuance.

Vestiges of these approaches linger to this day. As a case in point, some years ago I curated an exhibition on water history that included a dowsing rod, a forked deciduous branch that, in the hands of a gifted “water witch,” supposedly detects subterranean aquifers. Nomenclature for Museum Cataloguing, the standard classification system currently used by many North American museums, classifies dowsing rods, or “divining rods,” as “Mining and Mineral Harvesting Tools and Equipment,” within the broader “Category 4: Tools & Equipment for Materials.” On one level, this accurately reflects the customary use of the rods, to determine the best location to dig a well, or even to drill for oil or mine for gold. However, hydrologists would argue that the dowsing rod is a ritual talisman rather than a scientific tool. Why, then, does Nomenclature not classify a dowsing rod as a “Divination Object,” for which a classification also exists?

The answer, as Turner shows, is that museum classification and cataloguing systems are products of the assumptions and preoccupations of their creators, and the limitations of their tools. The classification of a Tlingit rattle as a musical instrument rather than a shamanic tool reflected one Victorian ethnologist’s desire to document the evolution of a form. In the process of doing so, key information about an object’s use, and even its cultural origin, was lost, or at the very least minimized. My dowsing rod example suggests colonialism’s corollary, the deference paid to European practices or superstitions that was not necessarily accorded to non-European belief systems. In both instances, the classification might affect how the object-turned-specimen is stored, cared for, and exhibited. The dowsing rod might be stored with other “mineral harvesting” tools such as drill bits and gold pans, instead of alongside crystal balls and séance gowns, while the ceremonial rattle is classed as a musical instrument and stored out of context, alongside other rattles but apart from objects from its community of origin.

In the age of reconciliation and repatriation, museum professionals struggle to overcome the challenges posed by colonialist “legacy data.” The decisions of past curators, and the layering of successive cataloguing systems on top of each other, can frustrate our efforts to reconstruct divided collections, to provide meaningful collections access for stakeholders, and to present artifacts to the public in accurate and engaging ways. Technology offers some solutions: Turner notes that new collections management software — designed, as one systems specialist once described it to me, for “the Google generation,” who wish to access information from a variety of entry points — allows for more nuance in cataloguing than does a binary McBee keysort card, and this bodes well for cataloguing new acquisitions. But systematically revisiting, revising, and reconciling decades’ worth of accumulated catalogue records is often beyond the means of museums and other memory institutions.

Yet understanding the problem and its source is a good starting point. Turner has made an important contribution in reminding museum professionals and museum enthusiasts alike that institutional memory in all its physical forms can shape collective memory in unexpected ways: museum collections document not only the lives and cultures of their “subjects,” but also those of museum staff, whose interests and biases underlie even the most mundane of museological practices. To understand the historical functioning of the museum, and to consider how its future function might be more equitable and inclusive, there is no better place to start than the catalogue.

*

Forrest Pass is a curator in the Exhibitions and Online Content Division at Library and Archives Canada. A cultural and material historian, he has worked previously at the Canadian Museum of History and the City of Ottawa Museums where he curated exhibitions and contributed to collections development and documentation projects. He is rather fond of card catalogues. Editor’s note: Forrest Pass has also reviewed books by Maddie Leach and Michael Kluckner, Philippe Tortell, Mark Turin, & Margot Young, and Tom Hawthorn for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1116 Politics on a punch card”