1135 An Islamic-Canadian journey

The Colour of God

by Ayesha S. Chaudhry

Toronto: Simon and Schuster Canada (Oneworld Publications), 2021

$30.00 / 9781786079251

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

Sibghatullah, “the colour of God” in Qur’anic Arabic, is the name of the author’s little nephew, whose sudden death at the age of 4 provides a frame for Ayesha Chaudhry’s narrative. Within the frame we find anger, sorrow, comedy, triumph, defeat, questions, answers, beauty, horror, hate and a great deal of love.

Sibghatullah, “the colour of God” in Qur’anic Arabic, is the name of the author’s little nephew, whose sudden death at the age of 4 provides a frame for Ayesha Chaudhry’s narrative. Within the frame we find anger, sorrow, comedy, triumph, defeat, questions, answers, beauty, horror, hate and a great deal of love.

Her previous book Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition: Ethics, Law, and the Muslim Discourse on Gender (Oxford University Press, 2014) wrestled with the interpretation of a Qur’anic verse which seems to condone wife-beating. Despite her scholarship — she is a Professor of Gender and Islamic Studies at UBC — Chaudhry was blamed for approaching the topic personally and with passion, as if such an approach, even within academia, should be judged blameworthy.

The Colour of God is unashamedly personal. “Blame” and “shame” are related, and Chaudhry confronts both concepts throughout the book. In Salman Rushdie’s novel titled Shame a daughter is “the incarnation of [her parents’] shame.” Both writers are concerned with topics larger than their inherited roots in Pakistan and Islam. According to Chaudhry, hers is “a universal story, a story about belonging and alienation, about finding community and meaning in the construction of a life.”

In Part I, “Anguish,” only five pages long, the author learns of the child’s death and realises she must “go back and rethink everything.” Part II’s 200 pages follow the rethinking process as she unfolds her personal story within the story of her Islamic-Canadian family.

Her parents immigrated to Canada from Pakistan in the 1970s. They were hardworking, eager to assimilate, and only moderately religious, but implacable racism and xenophobia drove them to return to Pakistan. The Dream of Return proved to be an illusion; they did not fit in there either: “the cruel fact of immigration is that once you leave, you never really have a home.” After several attempts, they gave up and stayed in Canada, preferring rejection by strangers to rejection by their own people, and shifting their racial identity into a hyper-emphasis on a religious identity new to them, that of ultra-conservative puritan Muslims.

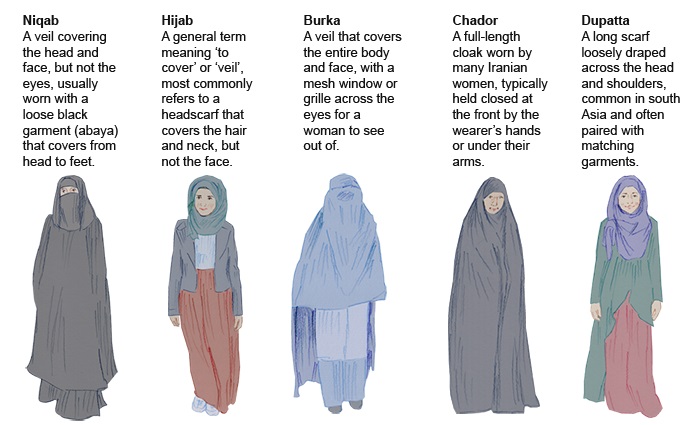

“The year I was born, my family joined a cult,” Chaudhry tell us. She was Canadian-born into a house filled with the religious zeal of new converts. Her mother wore the burqa, covering body and face not because of Muslim patriarchy but as a shield from racism. In their commitment to anti-assimilation, her parents became the caricatures invented by others.

Of course it was not all invented in Canada, and that is a major part of the irony. Her parents when children had lived through the horrific trauma of the Pakistan-India Partition and in their new country tried to live something other than the religiosity of their own parents. Chaudhry is not sure whether her maternal grandfather was fiercely pious or tyrannical and misogynistic. She comes to believe that his actions are matters of power and entitlement, less about Allah than about himself. When his daughter arrived at his door from the airport after the long flight from Canada, with her burqa still in her suitcase, he shames her, but it was his own shame he worried about; the same shame which had made him abruptly halt her schooling so she could care for an elderly relative because he would not face the disgrace of being known to hire strangers to perform the task. Only many years later does that daughter, Ayesha’s mother, realise she has inflicted this shame upon her own children.

Yet Ayesha is proud of her mother’s accomplishments:

She put six children through university. She became a religious scholar in her own right. She taught herself Qur’anic exegesis, reading Qur’anic commentaries in Urdu, in her basement study, poring over books, transcribing audio lectures verbatim. She’s taught Qur’an classes in that basement for several decades, and continues to do so today…. And she has lectured on the Qur’an to all-female audiences on the first Saturday of every month for three decades now. When people ask me how I came to be a professor in Islamic Studies, the answer is obvious. I’m just trying to be like my mother.

Tanzeem, the Islamic sect which Chaudhry’s parents joined, envisioned a Khilafa, a political order in which God is the sovereign, represented by the Khalifa, his vice-regent, an ironic mimicry of the sovereign of the British Empire who was represented in India by her vice-regent: “Among the crimes of colonialism is that it stole our imaginations, so that even our imagination of ourselves, even our resistance is fashioned in its image.” The law was Sharia law, stricter and more obsessed with purity than “mainstream” Islam. Although this sect was not violent, at least not physically or publicly violent, parents used the threat of violence to enforce their will with fear when shame was not sufficient.

Ayesha Chaudhry wore niqab throughout her high school years. Despite their isolation there were happy times for the six children and their parents. “Fundamentalist Islam,” she explains, “made me feel like I belonged to something bigger. It staved off my experiences with racism, which I only really fully encountered in all its ugliness once I removed my niqab and hijab, exposing my brown skin to the world.” Eventually she discarded the outer garments, but not her Muslim identity: “I believed Islam was special and I felt lucky to be Muslim. I still do.”

She spent six years at the University of Toronto without discovering the city beyond the campus. She studied, met people, and explored ideas, all within a safe circumscribed space, and found out that “it’s hard to work out in a niqab.”

Influenced by cult leaders, one of them a White Muslim evangelist, she dreamed of a Muslim homeland which did not exist and imagined “real” Muslims as desert Bedouins. One of the many ironies examined and experienced by Chaudhry is that of the “Orient” buying into the fictional scenario of Orientalism. Visiting Syria, she found a civilisation not all that different from the one she had left in North America. She also found that one can be sexually harassed while jet-skiing on the Mediterranean and wearing a niqab. On this occasion, she was unable to share what has happened to her with her friend who has also been insulted: “the shame spilled out of me and enveloped her.” She offered no solace, focussed on only her private shame, blaming herself for the failures of patriarchy.

Shame involves an acute awareness of the body. In some Islamic legal texts women’s bodies are shamed as a pollutant that must be covered, but in Canadian society it is the carefully covered Islamic body which may be seen as defiling the idea of a Canadian. Cover the body, or uncover the body: neither extreme is interested in the humanity of the women covered or uncovered. In a chapter entirely devoted to hair — too much hair, too little hair — Chaudhry muses: “How much I had to hate my body to suffer so deeply to alter it, to make it beautiful. To make it clean. To make it good.” Beauty is weaponised, made political, and she wonders: “What if the only way to be clean is knowing we are already clean?”

Puritanism, the religious attitude that rejects the body and human impulses, is not, we know, exclusive to Islam. It “transgresses religious and racial boundaries.” Wherever Puritanism occurs — mosques, mega-churches or a community blog — it is rooted in self-hate. The author, remember, is a teacher of Gender as well as Islamic studies: “God is transformed from a lover anxiously awaiting the return of her beloved, to a loan shark demanding the return of his investment.” [My italics highlight the gendered pronouns.] Puritanism depends on community policing, whether on Facebook or in a well-intentioned email. We are the recipients every day on social media of dicta formatted to resemble the stone tablets on which Moses received the Ten Commandments. Thou shalt wear a mask. Thou shalt not wear a mask. Thou shalt vote for this person. Thou shalt vote for that person.

What is the difference between an extremist and an idealist? “Do we only label people extremists when we are scared of them and their ideas? Should we be surprised when she declares that “Perhaps the most seductive siren call of extremism I have encountered is white feminism.” There are many reasons why Muslim women may choose to cover or uncover, and yet even among her academic colleagues there is a “self-righteous imagination” for which veils are “more outrageous than bombs.”

Chaudhry repudiates the “Clash of Civilisations” narrative as “a simplistic and stupid idea … a cop-out.” No one, “East” or “West,” has an essential nature, she insists. “We transform and are created anew by our circumstances all the time.”

And so, she warns, “Beware the one who seeks to save you on the assumption of their own exceptionalism,” and “There is no simple, uncomplicated person. No one fits in a box. Ever. ” Stuck between stereotypes, there is no space to just be.

Returning to Sibghatullah, the Colour of God, Part III grows from the grief and mourning around the child’s death. Women are forbidden to be present at the graveside, but his mother, Ayesha’s sister, insists. There against her will, his grandmother, Ayesha’s mother, whispers “You broke God’s law today by bringing us to the cemetery. You will have to answer for this.” [Italics are the author’s]. But her protest comes “in between sobs, through the tears and pain.” There is so much love mingled with the shame and anger.

The love is for people but also for her faith, for Islam itself. Meditating on the Islamic cycle of prayer from birth to death, Chaudhry turns her rage towards sorrow, some of the sorrow being sorrow for how shame was one of our primary teachers, and how shame is a partition that separates where love should unite. Returning to Sibghoo’s grave a few years later, she finds black raspberries growing nearby, and her conclusion is an elegy. “They were sweet. Sweet too where sorrow is. Sweet too where sorrow is.” Then comes reassurance from the Qu’ran in Arabic and translated: “We are God’s and to God we return.”

Among the many ironies which the author illuminates is one she could not have foreseen. Her book is published in a year when everyone is being told to cover our faces, and those of us with uncovered faces are shamed. By the time we emerge from the Pandemic, will we have become accustomed to seeing CBC’s Ginella Massa conducting interviews on The National while wearing hijab? I hope so.

So, being warned that the pages contain much that is infuriating, shocking, and much that is beautiful, readers might keep in mind Ayesha Chaudhry’s plea: “I ask you, dear reader, to please avoid simplistic, exotic, dehumanised conclusions from this story. Try to find yourself in it. Look harder. You are here.”

P.S. The Massy Arts Society hosted a Zoom launch for The Colour of God on May 18, 2021. The conversation between Ayesha Chaudhry and political science scholar Sarah Munawar and the subsequent Q&A touched on topics concerning finding voice and identifying listener, on writing this particular book while working in an academic setting, on self-love, self-hate, body theory, regret for our inability to save our parents, and the probable impossibility of decolonisation — among other topics. I could double the length of this review, or I could give you the link for the Facebook video.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve writes about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. She co-founded the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina on Gabriola Island. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: Phyllis Reeve has also reviewed books by Sylvia Olsen, P.K. Page (Margaret Steffler, ed.), Peggy Lynn Kelly & Carole Gerson, Iain Lawrence, Michael Kluckner, Jack Lohman, Mona Fertig, Lara Campbell, Ken Lum, and Ian Hampton, among others.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1135 An Islamic-Canadian journey”