1104 The call of the Kootenay

ORMSBY REVIEW PRESS: Frederick Paget Norbury, Chapter Two: Push and Pull: Tommy Norbury and Emigration

by Brenda Callaghan

*

Editor’s note: we are pleased to present Chapter 2 of Brenda Callaghan’s hitherto unpublished biography, Frederick Paget Norbury, Remittance Man or Gentleman Immigrant? The Story of an Englishman in Canada. Earlier in 2021 we published the Introduction and Chapter 1.

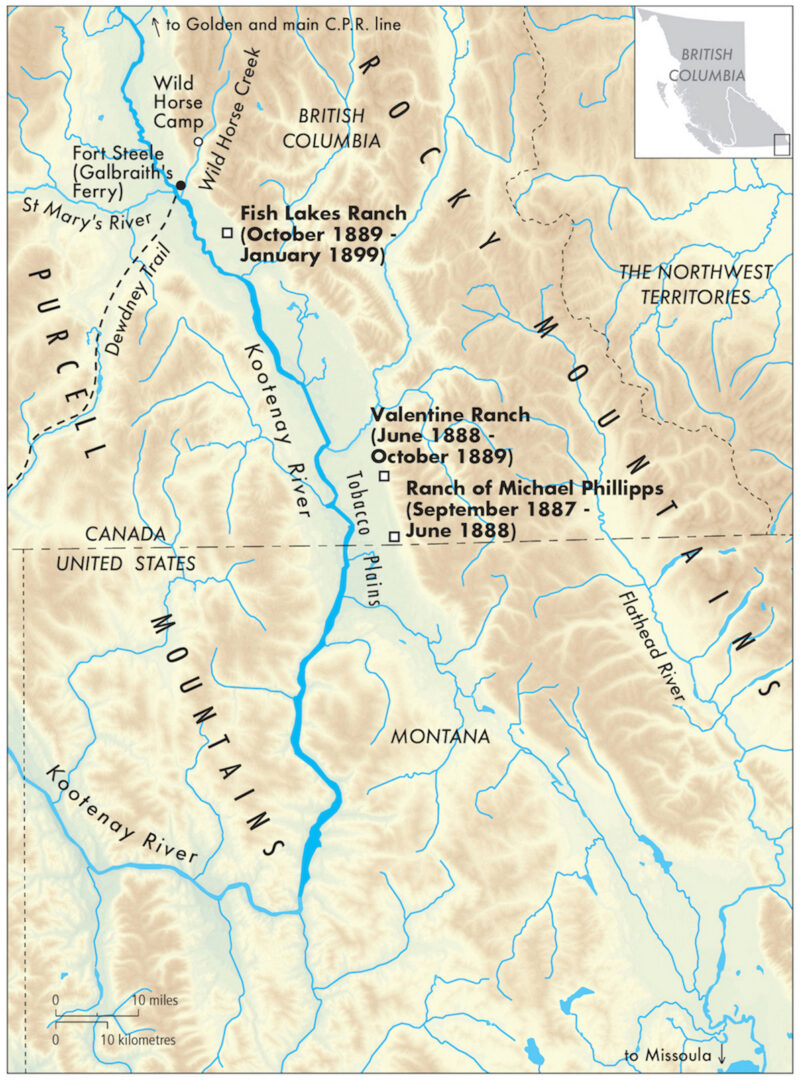

In 1887, Tommy (Frederick Paget) Norbury, who grew up on and eventually inherited an estate in England, became one of the first immigrants to travel west to British Columbia on the newly-completed Canadian Pacific Railway. Norbury (1867-1940) would work in the East Kootenay as rancher, Justice of the Peace, Stipendiary Magistrate, and Special Constable.

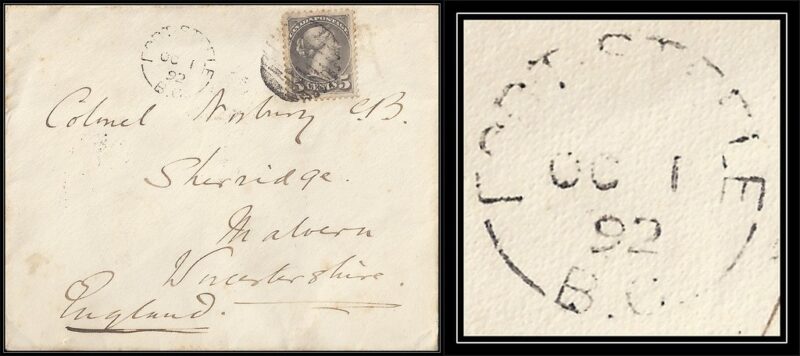

In 1898, Norbury returned to Sherridge House, near the village of Leigh Sinton, near Malvern, Worcestershire, having spent a most productive and fruitful 11 years in BC.

Sadly, Brenda Callaghan died in 2o18 before she could see the book published in The Ormsby Review Press. (Please see her biography at the foot of this post). Callaghan’s full 135,000-word manuscript of Frederick Paget Norbury, “Remittance Man” or Gentleman Immigrant? The Story of an Englishman in Canada, will be published in The Ormsby Review over the coming months, and simultaneously in The Ormsby Review Press.

We thank Brenda’s husband, Tim Gould, and her daughter, Natasha Schorb, for the opportunity to publish Frederick Paget Norbury online here. — Richard Mackie

*

Before we hear Tommy tell his story of his journey to Canada and his time in the East Kootenay, we need to know why this particular young man chose to come to live in British Columbia. For that matter, what induced him to leave England in the first place? These are complicated questions, and any attempt to explain this young man’s individual decision to emigrate must take into account the context in which that decision was made. In order to understand fully why Norbury and many others like him came to live in British Columbia, we must look very carefully not only at the family background of Tommy himself, but also at the migration history of both England and Canada.

1. Family Background

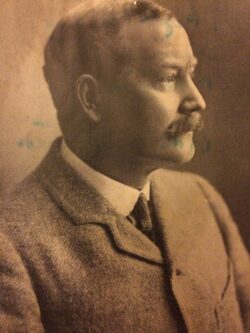

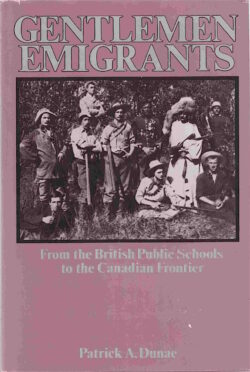

Tommy Norbury falls squarely within the category of “gentleman immigrant,” which for many reasons was a proportionally significant group to enter British Columbia in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Tommy Norbury came from a fairly privileged background. Born Frederick Paget Norbury in Malvern, Worcestershire, England, in 1867, he was the second son of Thomas Coningsby Norbury, and his wife Gertrude. His father appears to have lived the life of a country gentleman, and as the principal landowner in the locality, he undertook responsibilities and roles commensurate with his status. He acted as Deputy Lieutenant for the county of Worcestershire, and Justice of the Peace for Worcestershire and Herefordshire, for example. Norbury senior had served in the 6th Dragoon Guards, had seen action in the Crimea, and later was a colonel in the Worcestershire militia. Tommy had an older brother, Coni, two years his senior, a younger brother Billy, and five older sisters: Beatrice, Nell, Winifred, Florence and Kitty. The family owned and occupied Sherridge House, a small country house just outside of the village of Leigh in Worcestershire.

The maternal side of Tommy’s family was socially elevated, and in fact derived from the Irish nobility. Tommy’s mother Gertrude, was of the O’Grady family, and was the second of eleven children born to the second Viscount Guillimore of Limmerick. The Norburys were somewhat less grand. Certainly, Sherridge House had been the family home for several generations, and although Norbury senior was the chief landowner in the district, he was by no means a major player on the national stage, and he occupied a fairly modest position in the landed hierarchy. Strictly speaking, he was not of the established aristocracy, for the family owed their privileged status as much to money made in industry, as to inherited wealth in land. In 1827, Tommy’s paternal grandfather, Thomas Jones of Sherridge, had married the only child of Thomas Coningsby Norbury of Droitwich, an heiress whose family had made money in the salt business. When his father-in-law died in 1840, not only did Thomas Jones benefit from the large fortune his wife inherited, he also adopted his wife’s family name, and the heraldic Norbury crest. Family lore has it that this name-change was a condition of marriage imposed by the father of the bride, and it may be that the latter, having no sons, was attempting to ensure the continuation of the family name.

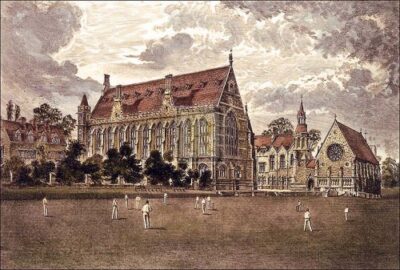

In the tradition of upper-class English families, Norbury senior (Tommy’s father) had received a public school and university education. He attended Eton College and Oxford University and his sons, Coni, Tommy and Billy all attended Clifton College, a newer public school. Although Coni had decided to pursue a military career (perhaps influenced and assisted by his father’s own military background), as the eldest son he was heir to the Norbury estates. But as far as the younger sons were concerned, their future was far less certain. They must “shift for themselves.”

2. The Changing Fortunes of English Landowners

Although the traditional laws of primogeniture (by which the eldest son of a landowning-family was sole heir to his father’s estate) were no longer strictly applied by the late nineteenth-century, and individual families might modify inheritance practices to suit their particular circumstances, as a ”second son” Tommy Norbury found himself in a dilemma. The problem was, that notwithstanding his innate ability as an agriculturalist, he might never be able to afford his own farm. His father had sent him to learn farming from a Mr. Grasset, an experienced farmer. Yet it was entirely possible that Tommy would never become a financially successful farmer and landowner. If the inheritance laws were strictly applied, upon Colonel Norbury’s death Tommy’s elder brother Coni stood to inherit the entire family estate. If not, and a more equitable distribution were to be made, Tommy would inherit a partial interest in his father’s estate which might or might not afford him a living. And if he tried his hand at something else, there were tremendous hurdles to be overcome.

The latter decades of the nineteenth century were not very promising for England’s wealthiest classes. Tommy Norbury came from a social group which was finding itself in increasing financial difficulty. From the late 1870s on, England was suffering under the effects of an economic slump. The land-owning elite was particularly hard-hit, as gentlemen of means found themselves subjected to increasing levels of taxation. Not only that, but non-inheriting younger-sons were faced with the prospect of the closing-off of taken-for-granted employment opportunities.

Younger sons of landowners had traditionally anticipated careers in the army, the diplomatic service, the church, the law, but they were now forced to compete for these positions with the professionally-trained sons of the less well-off. England was changing, and now sons of lower- and middle-class parents had access to educational opportunities denied them in previous centuries, opportunities to learn skills which they were able to bring to the professions previously reserved for the (largely untrained) sons of the wealthy. True, other types of careers were opening up in the burgeoning industries, but as Britain moved towards a more democratic, egalitarian society, a ”public school” education with its stress on the classics and character-development through team games, appeared to be an inappropriate preparation for a young man entering an increasingly technical, competitive commercial economy.

Thus, talented lower-class boys with a more practical, technical education provided formidable competition not only for the more traditional careers favoured by upper-class “second sons,” but also for positions spawned by a newly industrialised society. There is a strange irony here, though, because the anachronistic “public schools” had mushroomed in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, a response to the demands made by many upwardly-mobile industrialists and wealthy businessmen who had themselves prospered in industry and commerce, yet had no desire to see their sons enter the same fields. Bent on endowing their sons with “gentlemanly” attributes, they had no wish to encourage their sons in technical pursuits, and instead aspired to see them join the ranks of the landed classes. Thus, as the well-educated sons of the lower classes now moved into professional and technical careers of all descriptions, younger sons of industrialists competed with the younger sons of the traditional aristocracy and the gentry for careers once reserved for an exclusive elite, and it became abundantly clear that society would be unable to provide sufficient avenues for all the elite young gents wanting to exercise their “gentlemanly” qualities and still make a living.

Thus it was that in the latter part of the nineteenth century, worried parents increasingly looked overseas for a solution to the dilemma of their “superfluous” offspring.

3. Changing Views on Emigration

Although the latter decades of the nineteenth century, and in particular the period up to 1914, saw the arrival in British Columbia of many upper-class young Englishmen (and English persons generally), prior to the mid-nineteenth century the idea of emigration to Canada or anywhere else had held little appeal for members of Tommy Norbury’s social stratum. Tainted at best with the idea of poverty, at worst with the spectre of transportation and convicted felons, it was a step only the desperate would take, and then with trepidation. During difficult economic times poor people throughout the United Kingdom had migrated under the sponsorship of charities or friendly societies, and occasionally landlords who acted either out of philanthropic motives, or who simply wanted to get rid of unwanted tenants. Between 1760 and 1850 group migration of persons under the patronage of British noblemen or philanthropists had been the norm.

Negative attitudes to emigration ultimately faded as the imperative to populate and “civilize” the British Empire gained momentum, and thenceforth emigration gained a degree of “respectability.” Colonization of far-flung parts of the world by the British middle classes as a means of exporting British values to hitherto “uncivilized” parts of the Empire became increasingly important as Britain’s empire grew. British social theorists, most notably Edward Gibbon Wakefield (1796-1862) were tireless in their efforts to bring the matter of emigration before the British public. Wakefield propounded his theory of systematic colonization as a solution to a perceived social crisis occurring in Britain in the early decades of the nineteenth century. He argued that Britain’s many social ills: overpopulation, poverty and urban crime for example, could be greatly ameliorated or eradicated if only more British people of means would emigrate to the colonies, buy land, and employ “deserving” labouring people to work it. His desire was to make emigration self-funding and at the same time to recreate overseas the social structure of England. This would not only solve growing social problems in the Motherland, it would help develop areas of Empire which had for too long remained economically unproductive and culturally backward. The stress by Wakefield and others on the social and cultural importance of middle-class migration to Empire-building did much to place emigration at centre-stage among the fashionable.

Faced by economic hardship, and now unable to guarantee their younger sons’ financial futures, the English upper classes saw emigration as a possible way out of a tricky situation. If the social theorists and migration enthusiasts were to be believed, not only would their sons be fulfilling their Imperial duty by settling Greater Britain with the “better sort” (a necessary requirement if English values were to be transplanted abroad) they would also be able to acquire land fairly cheaply, become gentlemen farmers, build up their estates, and soon enjoy the kind of leisured lifestyle which was now unavailable to all but the very wealthiest in the “Old Country.” Given that Tommy Norbury appeared to favour the life of an agriculturalist over a career in the any of the areas which had recently become so competitive, and that his prospects as a farmer and landowner in England were not good, emigration, the fashionable answer to many upper-class woes, became also a very attractive solution to this young man’s particular problems.

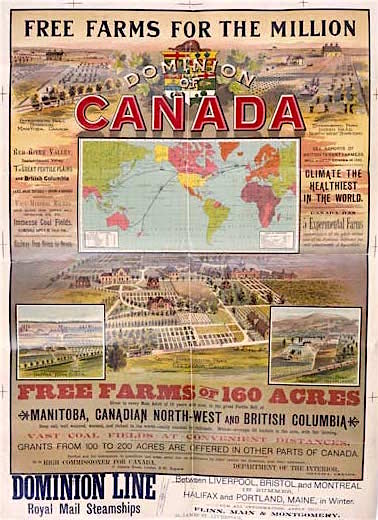

4. Canadian Measures to Encourage Immigration: The Migration Craze

Meanwhile, subsequent developments on the other side of the Atlantic had served to make Canada a particularly appealing destination for intending émigrés, particularly young men in Norbury’s predicament. Land might be in short supply and expensive in England, but there was plenty of it to be had – and cheaply – in Canada. Canada’s first Immigration Act was passed in 1869, during the administration of Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister. Under Macdonald, immigration from Europe became a major priority for both economic and nationalistic reasons. The Federal Government was extremely interested in populating the west of the country both as a means of unifying the nation and also to provide a market for eastern manufactured goods, and it came up with incentives of many kinds to draw immigrants to the new country.

With the entry of British Columbia into Confederation in 1871, and the subsequent completion of the transcontinental railway in 1886, it now became important, for political and economic reasons, to encourage settlement in the fledgling west coast province. Would-be settlers from throughout Europe began to take a serious interest in migration to Canada when, in 1896, Canada began a sustained and ambitious effort to encourage immigration. Although most newcomers settled the prairie provinces, a substantial number continued further west, and at the end of the nineteenth century and up until the First World War, record numbers of English migrants flocked to Western Canada, many to British Columbia.

Tommy Norbury’s arrival in Canada pre-dated by nine years the concerted attempt by the Federal Government to encourage immigration, and so it is not clear whether he was directly influenced to emigrate by any state incentives. Yet the attention directed upon the British Isles by Canada and the push by Britain to populate the former British Colonies throughout the late nineteenth century, were not limited to government initiatives alone, and many other influences were at work throughout the latter part of the nineteenth century, all geared to the same end.

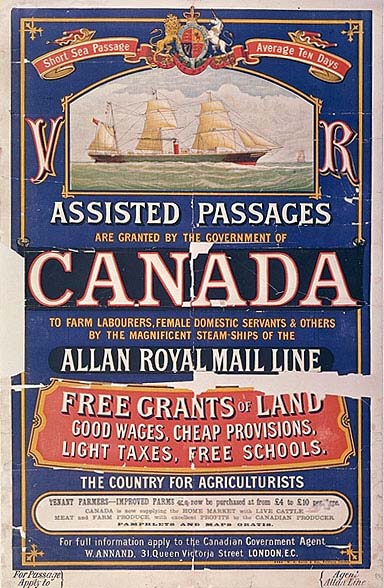

As a literate young man, Tommy must have been well aware of the huge surge in various types of emigration literature which flooded England and Europe during the latter decades of the nineteenth century. Pamphlets, newspaper articles and carefully-worded advertising material, put out by private companies with a vested interest in attracting migrants, began to command the attention of the British public. England was glutted by eye-catching material intended to lure the more adventurous to greener pastures overseas.

Steamship and railway companies stood to profit greatly by increased migration. Until the 1840s the voyage to the so-called New World had been lengthy, uncomfortable and fraught with dangers. Sailing vessels were poorly equipped for passenger travel and the journey was not for the faint-hearted. The arduous transatlantic journey, originally undertaken by wooden sailing vessels/paddle-wheelers, was not only uncomfortable, but had taken a considerable amount of time, ships being subjected to the whims of unpredictable wind- and sea-conditions. Built primarily to carry cargo, with few facilities for passengers, sailing vessels had taken a minimum of five weeks to complete the journey (and sometimes much longer). When English migrant Susanna Moodie set sail from Scotland in 1832 with her husband, sister and brother-in-law, it took her vessel nine weeks to reach Montreal, and for the last two weeks there was inadequate food and water.

The shipping lanes across the North Atlantic were of vital importance from economic, cultural and political points of view, because they linked the most advanced western nation states of Europe with those of the North American subcontinent, and the British Admiralty was interested in speeding up the mail service between England and North America. This need provided the incentive for the development of faster, more reliable ships, and ultimately the first iron steamships made their appearance. “The Great Circle Route” still remained particularly difficult to negotiate, however, because of the merging of cold and warm ocean currents off Newfoundland, which made for challenging conditions, and even the steamships found the route difficult. There were numerous disasters, but with the advent of the new vessels, journeys were now much shorter. In fact, the advent of steamships revolutionized travel to North America, cutting the journey time from over a month to mere weeks or even less.

The stress on better transatlantic communication and transportation had the benefit of greatly improving matters for intending migrants. Ships gradually became more comfortable and reliable. The reduction in crossing-time meant that not only was migration safer (it provided less opportunity for disease to strike and take hold, a very real danger on the old, slow and insanitary sailing vessels) it also meant that costs for individual passengers were reduced. More affordable tickets meant that migration was an option for far more people, and this was a great stimulus to the steamship industry, and to immigration into North America generally. By about 1870, almost all emigrants travelled by steamships owned and operated by companies which had emerged in the middle of the century to service the growing demand for transatlantic crossings. Between the 1850s and 1890s significant improvements to the service continued to be made, and by the end of the century British, German, and American companies vied with each other to offer the most up-to-date services on ever-faster vessels.

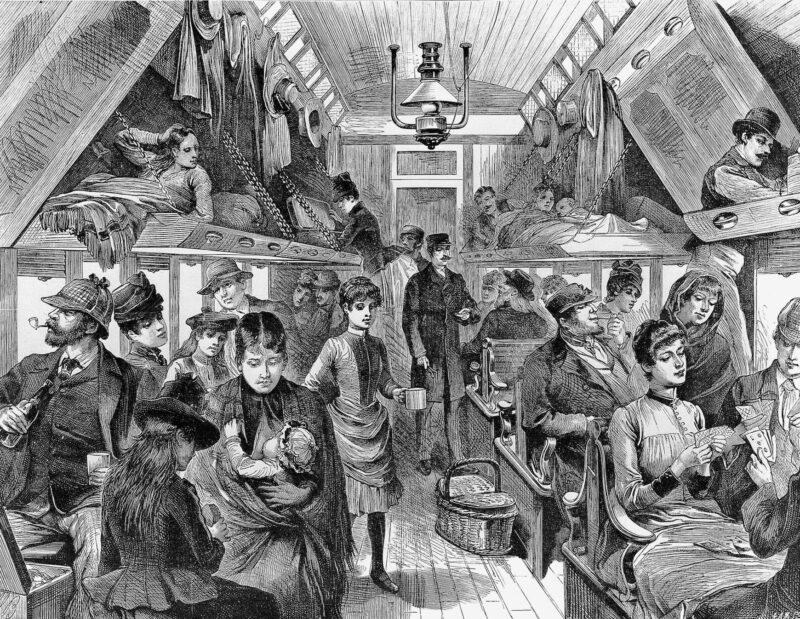

Even so, the majority of people who emigrated from Europe in the nineteenth century did not travel in great comfort. Most migrants had little money and needed to conserve what meagre resources they had, and so they purchased the cheapest “third-class” (or steerage) tickets which provided them with little more than a wooden bed-frame in a communal bedroom in the bowels of the ship. Facilities were primitive in the extreme, and until the 1890s such passengers were required to provide their own “kit” consisting of bedding, eating and drinking utensils, and so forth. Although some early accounts of steerage travel reported acceptable conditions, over the decades things appear to have deteriorated significantly. By the end of the nineteenth century, as migration from central Europe increased, accounts of horrific journeys were documented by some of those who survived the experience. The unsanitary conditions these people had to endure, the stench of their cramped and airless quarters, their complete lack of privacy, their degrading treatment by the crew, and the fact that some of them died before they reached North America, have produced an image of the typical immigrant as invariably a “third-class” or “steerage” passenger subjected to all manner of atrocities aboard ship.

However, as we shall see from Norbury’s own accounts of his journey, not all passengers bound for Canada travelled in such grotesque circumstances. In the late nineteenth-century, the steamship companies went to great lengths to encourage migration of the more “respectable” types of people. Wealthier travellers were advised by steamships run by the Allan and Cunard Lines, for example, that they would be able to travel in comfortable cabin- or saloon-class accommodation, far more luxurious and completely separate from the lowly steerage area below decks where the poorer passengers were crammed into unsanitary spaces more suited for cargo than people.

The Parisian, the ship upon which Tommy Norbury would ultimately travel to Canada, was the first large steamer to be constructed for the Allan Line Steamship Company, one of the most prominent and successful steamship companies to emerge in the nineteenth century. The company grew out of the seafaring activities of Captain Alexander Allan, who had begun his nautical career supplying Wellington’s army. Specifically, he shipped stores and cattle from Britain to Lisbon. After 1815, he shipped dry goods from Scotland for sale to Montreal aboard a fleet of sailing ships, eventually expanding his operations to include more trading vessels. Alexander Allan had five sons, the second of whom, Sir Hugh Allan, founded the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company. The success of the company was assured when, in the 1850s, it won the contract to carry the mails between Canada and Great Britain. This service had been undertaken previously by the highly successful Cunard Line, but having usurped the distinguished position of their rivals, the Allan Line vessels could now rightly claim the title of “Royal Mail Steamers.” By the 1880s, when Tommy Norbury made his trip to Canada, the Allan Line was one of the largest shipping concerns crossing the Atlantic. His voyage on the Parisian appears to have been a positive experience for the young Norbury. He travelled first-class and enjoyed numerous luxuries.

If the new steamship companies did their best to entice migrants overseas, the railway companies also spent a great deal of time and money trying to lure migrants. The new network of railways snaking their way across the United States and Canada made possible the settlement of hitherto inaccessible tracts of land, vast in extent. After the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1886, access to the prairies and British Columbia was assured. Now passengers arriving by sea into Montreal could transfer directly to the railway and connect with the west coast.

Most immigrants arriving in Canada in the late nineteenth century were transferred from steamship to train at one of the eastern seaports, usually Montreal, Quebec or Halifax, and travelled overland to the west of Canada in specially fitted “colonist cars” which conveyed both passengers and their effects at a cheap rate to their ultimate destination. Colonist cars were made of wood, were fairly basic in their design and held between sixty and seventy passengers. They were fitted with wooden benches and shelves that converted into berths at night, with curtains around each for privacy. Every car provided water, a washroom each for males and females, heaters, and a coal stove at the end of each car for cooking. Passengers were required to provide their own bedding and food. Often immigrants purchased the ship and rail ticket as a “package,” so that those travelling steerage would also travel colonist-class on the train, the most economical option. But, as we shall see from Norbury’s own accounts and those of other “first class” passengers, “gentlemen immigrants” travelled far more luxuriously.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Company saw a great financial opportunity, not only in initially transporting would-be settlers to their ultimate destination, but in the routine servicing of future communities thus created. But perhaps more importantly, the C.P.R. owned vast tracts of land granted to it by the Government under the terms of its railroad construction contract, and stood to make a fortune by selling that land on.

There were many other land speculators also with a vested interest in drawing settlers to Canada. Such companies, or in some cases, individuals, had played the “boosterism” card since early in the nineteenth century. By the end of the century many such companies were inundating the British Isles and elsewhere with promotional pamphlets, newspaper advertisements, magazine articles and so on, in a huge drive to cultivate interest in the purchase of land, usually site-unseen and too often of questionable worth.

5. English travel-writers and their Ilk

But not all the literature of the day written to entice migrants to Canada was produced by companies with a vested interest in such promotion, nor did it always originate in Canada. In the nineteenth century a new genre of travel-writing emerged, often undertaken by adventurous young English men (and a few women) who had themselves set out to explore distant parts of the globe, and who wrote in glowing terms of the opportunities which awaited migrants brave enough to take their chances in foreign parts. Although many books, produced in the form of “guides” and aimed at affluent young males, were highly sensationalized and exaggerated, often emphasizing the daring personal exploits of their writers, their authors appear to have been sincere in their belief that settlers in these new lands could expect to live an agreeable life, and in fact greatly improve on their existing living standards.

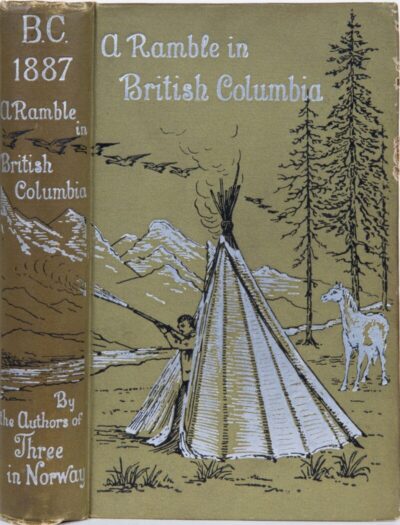

Two wealthy English gentlemen, James Arthur Lees and Walter John Clutterbuck, were representative of the young writers who did much to publicize the joys of travel to untried locations, and in particular the adventures to be had in the wilderness. They travelled to Canada at the same time as Norbury, and actually visited him shorty after his arrival. In the rather humorous guide/adventure book the two completed at the conclusion of their excursion in western Canada — J.A. Lees and W.J. Clutterbuck, B.C. 1887: A Ramble in British Columbia (London: Longman’s Green, 1888) — they claimed that their stated aim in spending so much time exploring B.C. was:

[T]o test its capabilities as a home for some of the public-school and university young men who, in this overcrowded old England of ours, every year find themselves more de trop… Emigration is the one hope left, and from all the information we could obtain in England, the region selected seemed likely to provide the necessary attractions for this class of colonists…

The two spent a great deal of time exploring the area where Norbury actually settled, and at the conclusion of their adventures they would claim that:

For English gentlemen with small capital who do not wish or expect to make fortunes, we fancy there is still plenty of room here. They could with moderate industry live comfortably (though not luxuriously) in a healthy climate, with the Union Jack over their heads, and the Queen’s writs and taxes so to speak on their doorstep; a fish in the river, a joint on the mountain, and game in the forest all ready for every man’s dinner; and three acres and a cow in the back-garden; in fact with all the surroundings which we are taught to believe necessary for a happy existence.

Further:

The country is almost everywhere beautiful, and in many ways is most desirable for a home… In the Kootenay valley there are already not a few Englishmen…. Both there and in the Columbia valley there are still plenty of spots worth taking up ….

Frequently writers such as these went to great lengths to interview established settlers and they produced some very detailed information about the costs involved and the lifestyle that could be expected.

Although this particular travel-book was published after Norbury’s arrival in Canada, there were a great many more like it, and there can be no doubt that numerous young men of Tommy Norbury’s ilk were drawn by the lure of adventure and new experiences described in personal accounts such as these, for they offered new possibilities as well as a chance to throw off rigid social conventions. It is interesting, too, that although many adventure books were written about the potential of the United States and other countries, the largest proportion of young men who emigrated chose to move to Canada. Thanks to the travel-writers, such would-be adventurers were convinced that the possibilities for exploration, self-fulfilment and freedom were greatest in what was perceived as the still challenging, and as yet untamed, wilderness of the far west of Canada — most notably British Columbia.

6. Other Family Reasons for Tommy’s Migration

It is probable that Tommy was influenced to migrate by all the factors described above. It also seems likely that, aside from the thorny problem of inheritance, other family reasons played into his ultimate decision. The family already had numerous connections with Canada. One of Tommy’s sisters, Kitty, had married into the Wilmot family, and Kitty’s brother-in-law, Teddy, was already farming in Canada at that time. Teddy Wilmot owned the Edge Hill Ranch at Pincher Creek, located in what was then known as the North West Territory, on the prairies to the east of the Rocky Mountains, and several letters presented here in upcoming chapter were written by or with reference to him. Teddy’s letters afforded a direct connection with Canada, and many would have contained a great deal of information about life there.

Then again, it is clear that Michael Phillipps (previously mentioned), a successful B.C. rancher of long-standing, the man into whose care Tommy was entrusted when he first arrived in the East Kootenay, and who was to become a great friend, had actually met and talked with Tommy when he visited England, and had a great influence on the impressionable young man. Phillipps was related (through his sister’s marriage) to Mr. Grasset, a local farmer who had agreed to teach Tommy to farm. On a rare visit to his relatives in England, Phillipps had occasion to meet and talk with Tommy, and on the strength of this amicable conversation, arrangements were made with Phillipps to receive the young man into his household.

Phillipps’s favourable description of ranching in Canada, in stark contrast to the poor prospects for success for the landless farmer in England, may well have been the main reason for Tommy’s decision to emigrate. Such connections with Canada not only served to legitimize emigration as a feasible ambition for the young man, they must have done much both to reassure his worried parents that their son would be in good hands during the initial difficult period of adjustment to a new situation, and to affirm in the family’s mind that successful ranching was indeed a possibility in Canada.

Another personal factor which was of great importance in Tommy’s decision to emigrate to Canada, and cannot be emphasised too much, was the influence of a man who was also well-known to the family, and who appears to have been a close and trusted friend. This man had many personal contacts with men already living in Canada, including Baillie-Grohman and Baker, and he would arrange passage for Tommy from England to Canada, and would act as his chaperone for the first half of the journey. He would later act in a similar capacity for Tommy’s younger brother Billy. This man was Mr. William Henry Barneby.

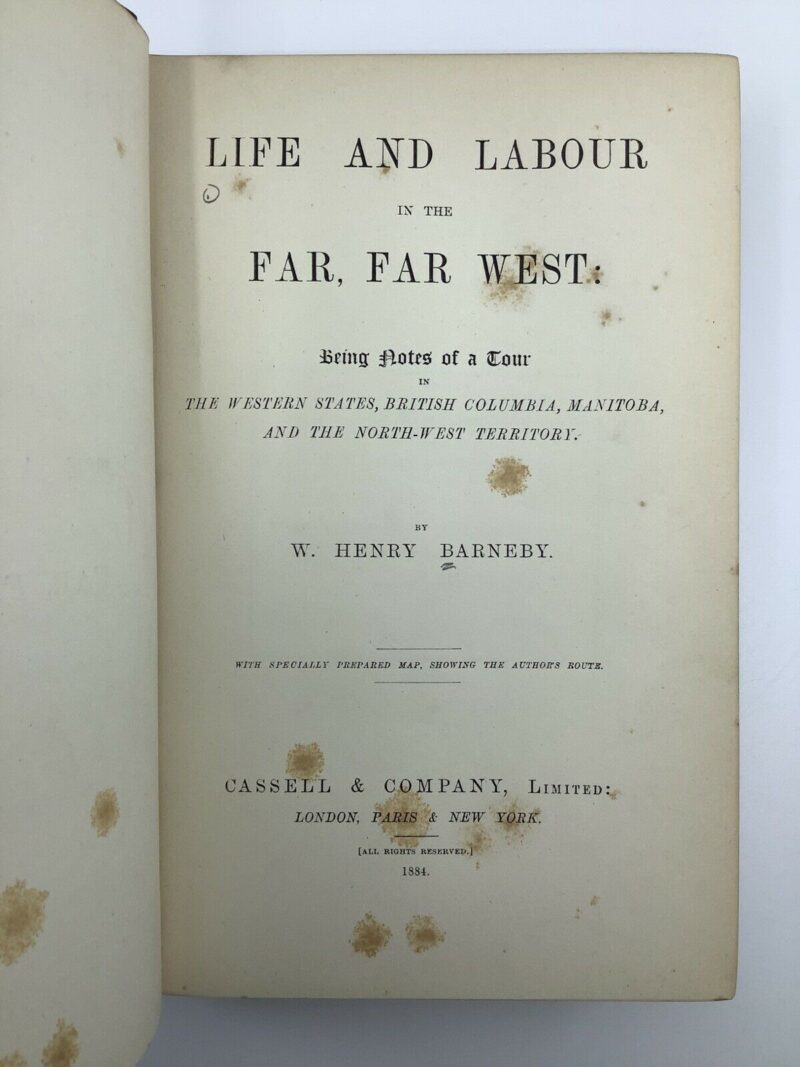

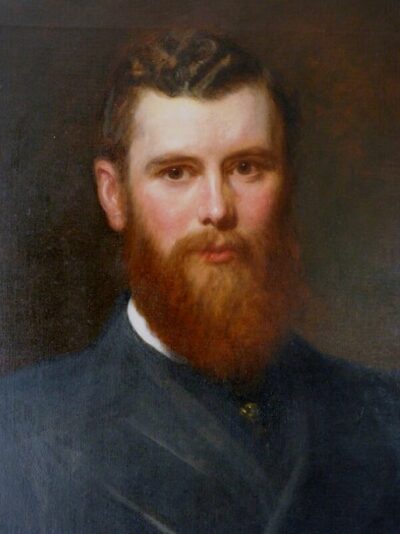

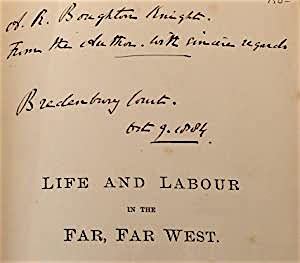

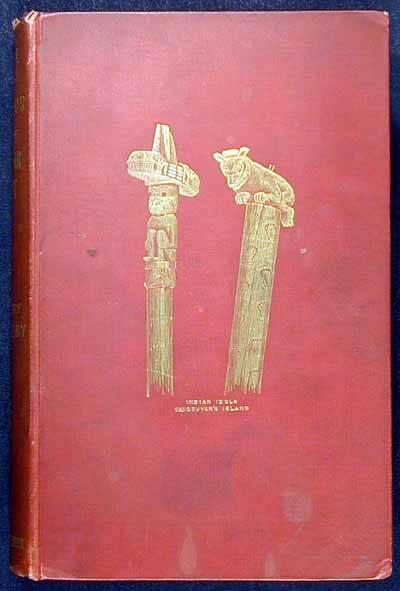

William Henry Barneby was a gentleman of similar social standing to Col. Norbury, Tommy’s father. A wealthy landowner, he lived at Bredenbury Court, a large country house (subsequently a school) in the neighbouring county of Herefordshire, where he was Deputy Lieutenant for the county and also a J.P. (Justice of the Peace). It is highly likely that he knew Col. Norbury through his work. Barneby was an avid traveller who spent extended periods of time in exotic locations. He visited Canada and the United States for the first time in the spring and summer of 1883, after having first travelled widely in Russia, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and other countries accompanied by two companions. The book that he undertook as a result of his visit to North America, Life and Labour in the Far Far West: Being Notes of a Tour in the Western States, British Columbia, Manitoba and the North West Territory, was written primarily as a travel journal which he sent in instalments back to his wife in England.

He made this trip, he reports, not only for personal pleasure, but also to collect information pertaining to farming and emigration, for the benefit of those who might be contemplating emigration to North America. In his book he waxes lyrical about the benefits to the gentleman immigrant of life in Canada. He describes at great length the advantages and possible drawbacks of the different places he visits, including the potential for employment to be found in each location. He notes the amount of money that can be earned, and how much it would cost to set up as a farmer in various locations. Tommy Norbury would eventually travel aboard The Parisian as one of a party organized and chaperoned by Mr. Henry Barneby. Barneby had arranged the young man’s passage and was personally acquainted with the Allan family. He was returning for a second visit to Canada, and had arranged to meet with a Mr. Brydges and his friend Baker, both residents of Canada [Charles John Brydges (1827-1889); see his entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography – Ed.].

Barneby does not write directly about the Kootenay District of British Columbia. His extensive travels did not take him into this area, although he is very friendly with Colonel Baker (previously-mentioned), originally from Kent, and now one of the most prominent residents of the East Kootenay, who must have furnished much information on the area. He also includes in his appendices a lengthy essay written by another friend and early settler in the East Kootenay area, the well-known entrepreneur William Adolph Baillie-Grohman, a prolific travel-writer himself, who did much to publicise the Canadian wilderness. Baillie-Grohman, of whom we have already heard, and who would eventually give his name to a community in the Columbia valley, close to where Norbury would settle, was convinced that the Kootenay district was paradise itself and described it in graphic terms and in some detail, as follows:

The country around the Upper Columbia Lakes … is an inviting “bunch grass” locality, which, to stock-raisers ought to be highly attractive, for not only will “ranches” here be exceedingly favourably situated as to railway communication by way of the Canadian Pacific, but the country is favoured by a mild winter climate…to a man desirous of starting into stock-raising with no more expansive aims, there are perhaps few more favourable locations….Throughout my six years rambles in the west and north west I have never seen anything at all like the Kootenay country .… it has almost everything the settler can desire….”

So confident is Baillie-Grohman of the area’s potential that he envisions, “on the breezy uplands of the Upper Kootenay River will roam herds of cattle and horses, fattened on the nutritious bunch-grass that covers the valley and foothills .…” Such accounts must have had enormous appeal to a young man from a landed background for whom the cost of setting up such a venture in England would have been prohibitively expensive.

Given his voracious appetite for reading, and the fact that Tommy’s journey was ultimately arranged and organised by Barneby, it is highly likely that Tommy Norbury was well-acquainted with the outpourings of Barneby and probably even Grohman. These glowing descriptions of what Canada could offer to the adventurous young man, coupled with the first-hand accounts of Michael Phillipps who actually lived such a life, would have done much to convince Tommy that emigration to Canada was the only way for him to achieve the life to which he aspired.

Thus, immediate and tangible personal and family reasons as well as factors and trends at work in society more generally served to both push and pull twenty-year-old Tommy Norbury to British Columbia. As a second son who could not expect to inherit enough of his father’s estate to guarantee a comfortable living, whose social equals were also feeling economically “squeezed” and were inclined to look favourably on emigration, he was drawn to a land where he was assured by many different authorities and advocates, that his prospects would be far more promising.

So it was that this young ‘”gentleman immigrant” left Liverpool, England, to travel aboard the steamship The Parisian, bound for Montreal, Canada, on 11th August 1887. What follows is Tommy’s story, told in his own words.

*

Brenda Callaghan, 1951-2018. Brenda Callaghan was born in Barrow-in-Furness, a small industrial town in the English county of Cumbia, in 1951. In defiance of local convention, Brenda remained in high school to earn A-levels and subsequently entered teacher training college, at what is now Leeds Beckett University, in 1969. Brenda’s teaching skills allowed her to immigrate to Canada in 1975 and eventually to fill teaching posts in Prince Rupert and Kitimat. Shortly after her daughter Natasha’s birth, Brenda’s first husband fell ill and left Brenda widowed in 1981. Brenda returned to academic studies in 1984 and over the following years was awarded a BA (Hons), an MA, and a PhD from the University of Victoria’s Department of History. Strongly affected by the loss of Natasha’s father, Brenda’s graduate and post-graduate research explored the cultural significance of customs associated with birth, death, and marriage in England’s post-industrial north. It was while conducting this research that Brenda met her second husband, Tim Gould, in Cumbria in 1991. During and following the completion of her PhD in 2000, Brenda worked as a sessional instructor at UVic and England’s Open University. In Cumbria, Brenda’s research was of broad public appeal and in the 1990s she established a reputation as an engaging guest speaker at local history societies. After settling with Tim in the East Kootenay region of BC in 2002, Brenda followed her interest in local history to the nearby Fort Steele Museum and Archives. It was there that Brenda, with the help of the curatorial staff, unearthed the letters of Frederick Paget Norbury. Brenda was no stuffy academic. Widely travelled, she saw much of Europe, North America, and the South Pacific. She ran a successful Bed & Breakfast in the Canadian Rockies, enjoyed live music and the theatre, was a scuba diver, keen hiker, and skier, and to the surprise of many, an enthusiastic long distance wilderness paddler.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1104 The call of the Kootenay”