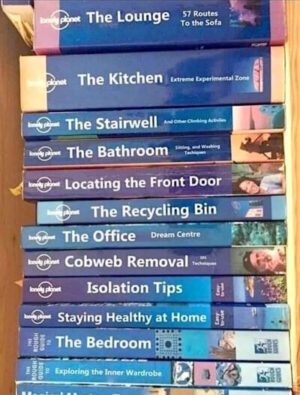

1081 A pre-pandemic Lonely Planet

Lonely Planet Vancouver and Victoria (8th edition)

by John Lee & Brendan Sainsbury

London: Carlton, 2020

$21.99 (US) / 9781787013612

Reviewed by Lauren Harding

*

Every time I open the familiar blue cover of a Lonely Planet book, I feel a wave of warm nostalgia. I came of age at the time nearly twenty years ago when the Lonely Planet brand was arguably at its zenith, with both a popular TV Series called Globe Trekker (I had a teenage crush on Ian Wright), and the early Lonely Planet website providing one of the first platforms for a forum-based exchange of travel tips before the ascendence of TripAdvisor.

Every time I open the familiar blue cover of a Lonely Planet book, I feel a wave of warm nostalgia. I came of age at the time nearly twenty years ago when the Lonely Planet brand was arguably at its zenith, with both a popular TV Series called Globe Trekker (I had a teenage crush on Ian Wright), and the early Lonely Planet website providing one of the first platforms for a forum-based exchange of travel tips before the ascendence of TripAdvisor.

As a travel-hungry teen I could afford more Lonely Planet books than plane tickets, and I read guidebooks cover to cover for places like Namibia and Bali that I have yet to visit. I distinctly remember my best friend and I in Grade 11, stuck indoors in our dull social studies classroom in what was to us the most mundane of landscapes, the snowy suburbs of west Edmonton (under the shadow of that behemoth of consumerism, West Edmonton Mall), making a list of the 99 countries we would visit before we were 99. Most of the destinations were chosen from the careful scanning of various Lonely Planet lists of top destinations.

Since that time, I have travelled, worked in tourism, and also studied tourism as a cultural practice from the ivory tower of academia. Lonely Planet guides are written for a certain type of traveller, and I am afraid I am no longer it. Now a married, middle-aged mother of two, I am not the carefree country-hopping backpacker that I was in the aughts. As guidebooks go, this new one — published in February 2020 — provides a decent introduction to the sights and culture of Vancouver and Victoria on the eve of the pandemic.

While this edition contains all the standard lists of accommodations, eateries, and attractions, the authors have also included a nice touch in their inclusion of “local knowledge” boxes that typically highlight overlooked local gems. I’m sure these additions are designed to maintain Lonely Planet’s brand as one that appeals to those who want to go off the beaten track. However, to some extent the Lonely Planet itself defines (defies?) the beaten track, and I’m quite happy that the authors have overlooked several of my own favourite haunts.

From a local perspective, this is important, as the post-Olympics tourist boom of the past decade has meant that favourite local spots are increasingly busy, not only with international tourists but also with domestic tourists from elsewhere in Canada and British Columbia. While I was very pleased to see some of my favourite spots on the authors lists, I was just as pleased to see some of my favourite spots left off the lists, directing the tourist hordes elsewhere.

I was thrilled that not a single one of my favourite trails was listed by name in Lonely Planet Vancouver and Victoria’s summary Best Hikes. That’s not to say that the picks were bad, it’s just that there are far better hidden gems, including trails accessible by public transit, that didn’t make the list, and I’m quite happy to keep it that way. Outdoor activities, especially hiking, remain one of Vancouver’s primary draws for both visitors and its outdoorsy local populace. I surprised to see no mention of safety protocols for playing outside in Vancouver’s wild backyard. I strongly urge all visitors, even if they are experienced outdoorspeople, to review North Shore Rescue’s list of essential things to bring before exploring our vast outdoors.

Some of the highlighted eateries and entertainment venues have not survived the pandemic, and, I predict, some won’t survive the predicted pandemic-adjacent economic downturn, particularly as Vancouver’s housing crisis continues to force middle-class Vancouverites to tighten their belts and shrink their entertainment budget. The authors do allude to the growing housing crisis as a major issue in both cities, and I’m glad more visitors to the city will be made aware of how this crisis continues to shape the cities and transform the demographics of their inhabitants.

My main critique of the guide as written can be summed up by the choice of the cover photo of the Stanley Park totem poles. The city of Vancouver is located on the unceded, ancestral, and still Indigenous occupied lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. The city of Victoria is located on the land of lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwegun) peoples and the Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ peoples whose historical relationships with the land continue to this day.

Furthermore, these Coast Salish peoples did not and largely do not carve totem poles. They had and continue to have a thriving visual art culture that included house posts, but the totem poles are a traditional cultural form of north and central coast Indigenous peoples. This needs to be said, as Indigenous art forms are connected to ideas of territory, property, and history, and the fetishization of totem poles (and stealing of them) by settlers is indicative of a general blindness of settlers to their cultural significance.

The cover of Lonely Planet Vancouver and Victoria features the Kakaso’Las Totem Pole, commissioned by Woodward’s Department Store and carved by Kwakwaka’wakw carver Ellen Neel in a style distinct from Coast Salish artistic traditions. The complex history of why the pole was carved and painted the way it was, and placed where it was, is not something I have the space to discuss in this short review, but I do want to point out that it is more a story of cross-cultural encounter than of local, ancient, Indigenous tradition.

The guide’s authors, not unexpectedly but still disappointingly, largely fail to mention Indigenous peoples as part of the community beyond their contributions to the visual art world and a brief mention of one Indigenous-operated restaurant. While the section on Vancouver history and culture does include the mention of the removals of Indigenous peoples from their former settlements and fishing sites, these removals, and Indigenous culture generally, are relegated to the historical past and disconnected from the guide’s narratives of the cities as contemporary, cosmopolitan, multi-cultural, hubs.

The narrative reproduced is what I have seen to be the dominant one in Canadian tourism, even in this so-called era of reconciliation, where Indigenous peoples are portrayed as part of a historic past rather than as a continuous and living culture. I suppose this is because this is a tourist guidebook, focused on selling Vancouver and Victoria as a destination, and highlighting the resilience of Indigenous people and their continued occupation of their unceded territory would mean having to discuss the “C” word (Colonialism, *gasp*), a term that is perhaps too politically charged for the Lonely Planet’s editors (although it should not be, as it is merely a descriptor for what happened).

Finally, the authors seem a little overly pre-occupied with beer and beer drinking, to the neglect of Vancouver’s other favourite legal and recreational drug, cannabis. This omission is ironic, given that the consumption of the latter is arguably more socially acceptable among Vancouverites than tobacco smoking. International tourists are at times rather flummoxed by the dirty looks they may get lighting up a cigarette on our public beaches (it is illegal to smoke any substance on public beaches here), when the smell of cannabis is as common as cherry blossoms on our spring evenings.

Overall and despite these critiques I enjoyed reading Lonely Planet Vancouver and Victoria. It was nice to see my home through the eyes of Lonely Planet and nostalgically recall the reverence I had for the guide as a youth. I was introduced to a few attractions that I have never heard of, which was very nice given that we are confined to exploring our own backyards for now. Would I recommend this guidebook to a traveller visiting from overseas? The short answer: yes. The long answer, yes, but with the insertion of a few caveats sourced from opinionated locals like me.

*

Lauren Harding received her doctorate in anthropology from the University of British Columbia. Her dissertation research was conducted on Huu-ay-aht and Ditidaht territory on the west coast of Vancouver Island in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. She is writing a cultural history of the West Coast Trail, with a focus on settler-Canadian recreation practices as a form of nation-building and the intersection between different cultural conceptions of wilderness and territory in the context of settler-colonialism. In other words, she studies hiking and camping! Her areas of academic interest include space and place theory, the anthropology of colonialism, environmental history, Canadian studies, and the anthropology of tourism. She teaches courses in critical tourism studies at Simon Fraser University. Editor’s note: Lauren Harding has reviewed books by Linda Mahood, Joanna Streetly, and Colin Coates for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster