#427 Counterculture wanderlust

Thumbing a Ride: Hitchhikers, Hostels, and Counterculture in Canada

by Linda Mahood

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2018

$32.95 / 9780774837347

Reviewed by Lauren Harding

First published November 19, 2018

*

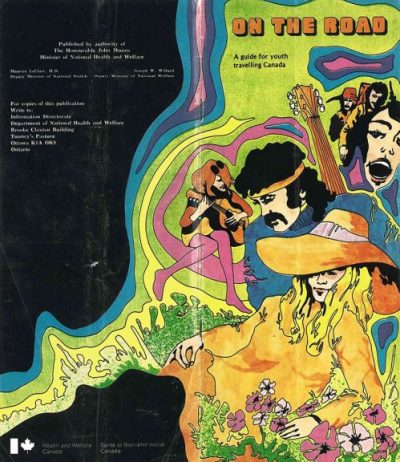

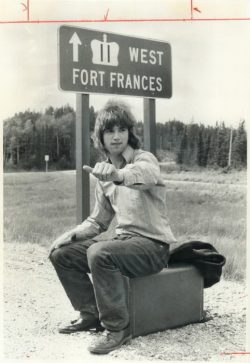

In this fascinating history, Linda Mahood takes a look at changing views of youth mobility in twentieth century Canada, from the early days of automobile travel to the youth culture of the 1970s, to the late twentieth century where hitching a ride was (and is) seen as dangerous and taboo. She links the rise of the modern teenager and automobile culture, and tracks the formation of two cultural practices in the Canadian context: hostelling and hitchhiking. Her text is more focused on the latter than the former, but she makes important links between the two.

In this fascinating history, Linda Mahood takes a look at changing views of youth mobility in twentieth century Canada, from the early days of automobile travel to the youth culture of the 1970s, to the late twentieth century where hitching a ride was (and is) seen as dangerous and taboo. She links the rise of the modern teenager and automobile culture, and tracks the formation of two cultural practices in the Canadian context: hostelling and hitchhiking. Her text is more focused on the latter than the former, but she makes important links between the two.

Mahood contends that the idea of youth travel as educational as well as recreational allowed both hostels and hitchhiking to take root as cultural formations in the twentieth century. She notes that both predate the countercultural hippie movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and that there was diversity within each. Hostels, for example, were more often in the early years associated with outdoor recreation than the “flophouses” of the hippie era. Mahood also notes demographic distinctions of race, gender, and class both among those who used hostels and who hitchhiked. She also identifies diversity within each of these, with both hostels and hitchhiking cultures taking on a distinctive countercultural element in the 1960s and 1970s, despite both pre-dating the advent of the “hippies.”

Although Mahood does to some extent explore the gendered and racialized nature of hitchhiking experiences, the majority of her history is focused on the Canadian middle class. This focus may be viewed as both a strength and a weakness: her focus is welcome because of the notable lack of thorough and critical research on the middle class, particularly as she does not take the middle class as a given norm but as a particular demographic formation. At the same time, her history does seem to have a lack of balance, with less attention paid to the practice of hitchhiking by the socially marginalized.

Mahood situates her discussion of youth mobility and alternative travel within pertinent tourism studies theory. She makes good use of the anthropological conception of rites of passage and the notion that youth travel, risk, and rebellion are intrinsic to this liminal stage of the life-crisis ritual. She posits that the risk-taking behaviour of hitchhiking linked to the crafting of identity and the accumulation of symbolic social status markers that identify alternative travel participants as possessing a special type of agency. Overall, Mahood’s use of relevant social theory regarding mobility, youth identity formation, and travel as ritual is very well done and she aptly portrays the social role and effects of youth mobility counterculture in the Canadian context.

Particularly strong is her analysis of the role of the first Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau (1968-1979) in creating social programs that both facilitated youth travel and also effectively attempted to manage it. Despite a wealth of public discourse that framed hitchhikers as social deviants, Mahood shows how the federal government under Trudeau attempted to frame youth travel as a positive social movement that allowed young Canadians to get to know their own vast country. This re-framing of an activity increasingly seen as deviant in the latter half of the twentieth century as a socially functional nation-building enterprise was, according to Mahood, met with both successes and failures, and she artfully tracks the bureaucratic efforts both to support and contain the young Canadian “hippies” of the 1970s.

Archival research, particularly newspaper articles and editorials and oral histories, makes up the bulk of Mahood’s data. While her oral history interviews both personalize and provide a necessarily richness to her history, most of those she interviewed were apparently representative of main segment of Canadian society she describes: those who were middle class youth in the 1960s and 1970s.

One issue with her snowball sampling method in collecting research participants is the fact that those with positive hitchhiking tales of their youth were more or most likely to respond with interest to her calls for research participants. Furthermore, it leaves one to wonder how her data would have differed had she sought out stories not only from those who represented a typically racialized white, heterosexual, baby-boomer middle class, but from those who hitchhiked due to necessity rather than choice: those who were socially marginalized because of their race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and gender presentation, and who hitchhiked not simply because of their association with the youth “hippie” movement and its associations with drugs, counterculture, and seeing the country.

Mahood does address this gap in her oral history research data by discussing the role that gender, sexuality, class, and race play in creating differences in hitchhiking experiences. But to do so, she relies primarily on archival data rather than first-person accounts (with the exception perhaps of some discussion of gender and sexuality).

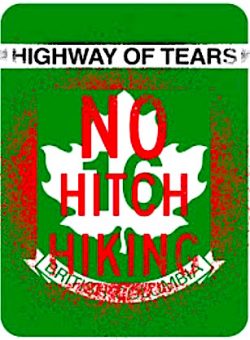

Collecting stories of those marginalized would be a difficult task, and was perhaps simply beyond the scope of her project. But as Greyhound cancels its western Canadian routes, including that on the infamous Highway of Tears (Highway 16), a further inclusion of stories of those who hitchhiked due to social precarity rather than wanderlust might have contributed in a more substantial way to contemporary discussions concerning mobility in Canada.

Mahood’s history is an excellent addition to recent historical scholarship addressing counter-cultural movements in Canada. Her work will be of interest not only to scholars but to those who have participated in hitchhiking and hostelling in this country, and who can appreciate the distinctive challenges and sheer adventure of travelling across Canada with little funds and lots of ground to cover.

My own less grandiose hitchhiking experience while working in my early twenties in the Canadian Rockies was at the forefront of my mind while reading Thumbing a Ride. This relates to another reason to read this book: it’s well-written and supplies an engaging narrative while at the same time providing enough scholarly substance to make it a notable academic work. In other words, reading this book is a good ride, with enough interesting sights to ponder along the way and the good company of fascinating anecdotes to make the journey worthwhile.

*

Lauren Harding is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia in the Department of Anthropology. Her dissertation research was conducted on Huu-ay-aht and Ditidaht territory on the west coast of Vancouver Island in Pacific Rim National Park Reserve. She is writing a cultural history of the West Coast Trail, with a focus on settler-Canadian recreation practices as a form of nation-building and the intersection between different cultural conceptions of wilderness and territory in the context of settler-colonialism. In other words, she studies hiking and camping! Her areas of academic interest include space and place theory, the anthropology of colonialism, environmental history, Canadian studies, and the anthropology of tourism.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.