1028 Christopher Tunnard’s gardens

Thinking a Modern Landscape Architecture, West & East: Christopher Tunnard, Sutemi Horiguchi

by Marc Treib

Novato, California: ORO Editions, 2020

$45.00 (US) / 9781943532780

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

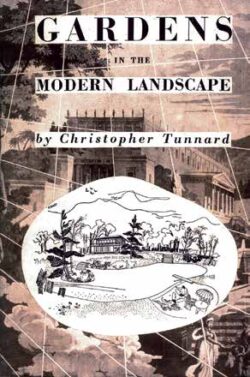

Thinking a Modern Landscape Architecture is a tale of two architects — or rather of two prominent books: Christopher Tunnard’s Gardens in the Modern Landscape (1948) and Sutemi Horiguchi’s Architectural Beauty in Japan (1956). Both books brought modernist aesthetics into play for landscape architecture, and in the process became seminal reference texts in the English-speaking world. Both Tunnard and Horiguchi practised as landscaped architects, both lectured and taught in the academies, and both were profoundly influential through their writings, if less so in the practice of the art. Both books would remain current for half a century. There were also parallels in how the two books came about. They emerged from previously published articles and lectures, relied on close collaborators for their production, were immensely popular, and have been much referenced and studied. Gardens in the Modern Landscape remains in print to the present day.

Thinking a Modern Landscape Architecture is a tale of two architects — or rather of two prominent books: Christopher Tunnard’s Gardens in the Modern Landscape (1948) and Sutemi Horiguchi’s Architectural Beauty in Japan (1956). Both books brought modernist aesthetics into play for landscape architecture, and in the process became seminal reference texts in the English-speaking world. Both Tunnard and Horiguchi practised as landscaped architects, both lectured and taught in the academies, and both were profoundly influential through their writings, if less so in the practice of the art. Both books would remain current for half a century. There were also parallels in how the two books came about. They emerged from previously published articles and lectures, relied on close collaborators for their production, were immensely popular, and have been much referenced and studied. Gardens in the Modern Landscape remains in print to the present day.

Interestingly, however, the two men never met. Christopher Tunnard (1910-1979), a Canadian and graduate of the Victoria College/McGill in 1928, completed his formal garden design training in England at the Royal Horticultural Society’s School of Horticulture at Wisley, Surrey. The School’s curriculum was intensely scientific and practical. His career then evolved from first working as a seed-testing scientist, then joining the very successful office of landscape architect and publicist Percy S. Crane, to finally opening his own office in Cobham, Surrey, in 1934. Along the way he took courses in technical drawing and building construction.

On opening his office, Tunnard was already in conversation and friendship with a number of soon-to-be profoundly influential and innovative design thinkers, a group that became the MARS (Modern Architecture Research Group). MARS saw itself as a sort of British branch of CIAM, Corbusier’s assembly of continental radical Modernists (Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne). As well as artists, designers, and architects who published in its journal Circle, the group included the staff and many contributors to the influential Architectural Review. Tunnard became a frequent contributor to the Review along with another journal, Landscape and Garden. The artistic milieu published in these journals included, among others, the sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore and the architects Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, and Maxwell Fry. Like the Europeans, the aesthetic roots of this strain of abstract modernist theory lie in Constructivism and Cubism. Tunnard contributed the notion of the “functional garden.”

The signal public expression of the “Martian” project was an exhibition held at the New Burlington Galleries, London, in January 1938. Tunnard organized one theme room titled “Architecture in Form and Purpose.” It included his landscape schemes illustrated by Gordon Cullen, who would remain Tunnard’s illustrator for his later published essays that ultimately became Gardens in the Modern Landscape. Interestingly, his earliest published essay for the latter examined the influences of Japanese garden design in Britain, a theme he would often return to and ultimately re-examine in the book.

While documenting Tunnard’s career, Treib notes a curious disconnect between his writings, which promoted the hard-edge geometric aesthetic of the Modernists, and his actual designs, which remained rooted in the English picturesque tradition. One signature of his design work was in the use of abstract sculpture pieces as pivotal elements in his garden viewscapes.

By the late 1930s, many Germans, including Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, had left for academic positions in the United States, and Tunnard was to join them. In 1939 he joined Gropius at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design where his reputation as a sought-after speaker and theoretical writer, rather than a practitioner, had paved the way.

In 1942, Tunnard returned to Canada to enlist in the Royal Canadian Engineers, but a year later was discharged for medical reasons — a blind right eye! He returned to Harvard under a fellowship that allowed him to study and travel, and then took up an academic appointment at Yale. One result was a new revised edition of Gardens, published in 1948, which included some of his American projects, but his teaching and research career at Yale increasingly turned to city planning, urban design, and historic conservation. When he finally travelled to Japan in the 1960 to participate in the World Design Conference he had already moved on from landscape architecture in his interests. There followed a number of award-winning books including The City of Man (1953), Man-made America: Chaos or Control (1964), and A World with a View: An Inquiry into the Nature of Scenic Values (1978).

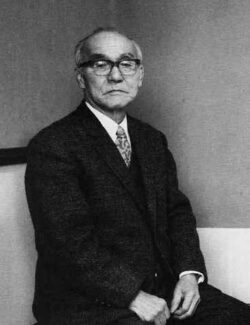

By the time of Tunnard’s Japan sojourn, Japanese garden landscape design was well ensconced in the Modern era, demonstrating that traditional principles could assume new forms for a better fit with contemporary architectural settings. One of the main contributors to this evolution was Sutemi Horiguchi.

Horiguchi (1895-1984), as fifth son in an agricultural family near Kyoto, could not inherit the family land and chose a professional career. Early in his architectural career he was very much subject to western European influences as a result of the mid-century forced opening of Japan and the establishment of the treaty ports such as Yokahama, Osaka, Nagasaki, and Kobe. In 1917, aged 22, he enrolled in engineering in Tokyo Imperial University, where he specialized in architecture. The curriculum was typical of Taisho period (1912-1925), rooted in the aesthetic formulae of Western neo-classicism. Garden design was not taught; gardening was an inherited career.

In Kyoto, the minimalist temple gardens of the classic Edo period style were eschewed in favour of the more luxuriant Heian period (795-1182) gardens of the aristocratic villas. These “stroll gardens” privileged the movement of the body and eye as a series of unfolding but controlled views and vistas. Pond edges, stepping stones, and pathways directed the eye in motion. Western elements such an expanses of lawn intruded on the traditional spatial components including gravel, water, or paving stone. An English professor, Josiah Conder, who had joined the Imperial University in 1887 as its first professor of architecture, brought English landscape design to his own commissions, and for a local wealthy merchant family he combined this with native plant materials. Conder rapidly became a student of Japanese garden design, publishing the two-volume Landscape Gardening in Japan (1893), a profoundly influential treatise for knowledge about Japanese garden history in the English-speaking world.

In protest against the stylistic formalism of his training, Horiguchi joined with a group of fellow graduates calling themselves the Bunriha Kinchiku-kai (Architects Secessionist Group). Pushing for a “New Architecture,” they looked for a modern Japanese architecture that would adapt native building traditions to contemporary lifestyles. The group proselytized their ideas through lectures and exhibitions. In 1919, they travelled to China where they were impressed with German Jugendstil applied to buildings in the German colony at Qingdao.

After graduating, Horiguchi travelled to Europe where he visited France, Austria, Germany, and England. In Germany, he acquired a substantial library of architectural books and periodicals. These European influences constantly reoccurred in his own private practice, in which he moved through references to German and English arts-and crafts to the spare abstract forms of 1920s Moderne. At the same time, he started to apply New Architecture precepts to the design of surrounding landscaping and garden courtyards of his houses. Early examples seem to combine Lutyenesque Romantic classicism and Tunnard’s geometric planning, with features and planting materials cherry-picked from various Japanese garden types and periods.

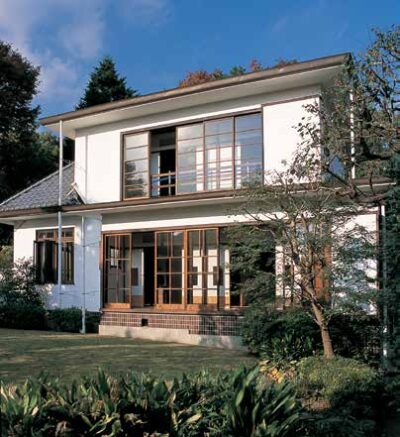

At the same time Horiguchi published articles in support of this “modernist” approach. In one of them, he offered up a theory of abstract beauty as an emotional response to function and organization. By 1934, he was able to pay exclusive attention to garden design in a key article titled “The Garden of the Autumn Grasses,” where he laid out the theoretical foundation for garden design in a modern Japan. His breakthrough, or breakout, was basing design not on a typology of traditional gardens but rather in the gold and silver ground panel paintings of the eighteenth-century Rimpa School. For Horiguchi, his elements of the Japanese garden such as rocks and plants could be isolated, almost as objects d’art in their own right, and set against unadorned background to be viewed from a verandah or framed by a window.

While writing “The Garden of the Autumn Grasses,” Horiguchi was designing the Okada house, a commission that illustrated these principles. Components of the garden look eerily like some of Tunnard’s designs of the period, while the overall scheme combines Japanese planting materials arranged so as to reference both Edo period dry gardens and Kyoto’s more lush planning tradition. This eclectic aesthetic was to provide Horiguchi with a design language he would apply in various iterations over the rest of career.

In 1946, he joined his alma mater, Tokyo University, as an instructor of architecture before moving to Meiji University in 1949 to assume a professorship and retiring in 1970. It was during this time that he assembled Architectural Beauty (published in English in 1956), followed by the equally seminal Tradition of the Japanese Garden (1962). As standard English references these replaced Jiro Harada’s Japanese Gardens (1936). Like Tunnard, Horiguchi collaborated in writing his books, but unlike Tunnard, Horiguchi’s collaborator was his student and art historian, Yoichiro Kojiro.

In summarizing the careers of Tunnard and Horiguchi, Treib observes numerous common themes. Both men were profoundly influential, more for their teaching and writing than their works. Both elaborated a theory that applied abstract expressionism to “modernize” landscape design in their respective context; but they relied heavily, and indeed insisted on, a thorough knowledge of garden histories and traditions as necessary cultural grounding. Finally, both men had to witness their theories put into practice by others more successfully than they themselves; ultimately, either because of client demand or their own training, both tended to fall back on vocabularies inherited from history.

*

Of particular interest for the Ormsby reader is the figure of Christopher Tunnard, who was born and brought up in Victoria. Treib ably provides early biographical detail with a discussion of the Englishness of Victoria, its imported local garden tradition, the famed Butchart Gardens, and the modern landscape painting tradition of the Group of Seven along with the expressionism of local artist Emily Carr, but Trieb admits to being somewhat mystified by Tunnard’s early and deep interest in Japanese Gardens.

A somewhat deeper appreciation of the horticultural scene in Victoria in the first few decades of the 20th century might have provided some hints. The truth is that while Victoria was often relegated to outpost-of-empire status, it was no cultural backwater in horticultural matters. Climate and location of course prompted this.

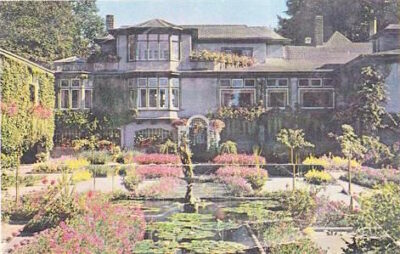

By the mid 1920s, Victoria was a hive of gardening activity with many professional practitioners serving a discriminating audience. Planters, gardeners, breeders, Chinese greenhouse growers, and nurserymen served a thriving market. These gardeners tailored their services to the numerous microclimates and soils of Victoria and the adjacent peninsula. Just as important were the women who created the must-have gardens into were which were set the bungalow cottages or more stately mansions designed by a local fraternity of arts-and-crafts architects led by Samuel Maclure and Francis Mawson Rattenbury. By the 1920s, the custom of opening private gardens to the public on Sundays (with some matrons offering tea) had become an established tradition. Most of the labour was supplied by a veritable army of immigrant Chinese gardeners.

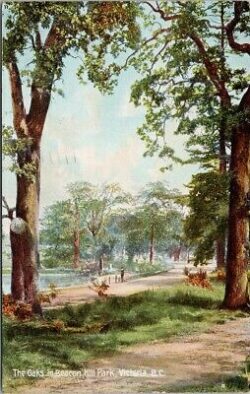

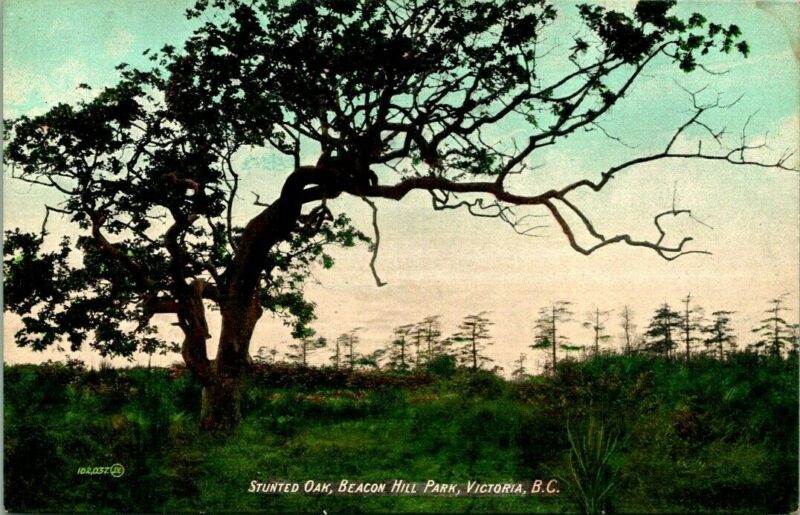

From Victoria’s very beginning, the colonial surveyor Joseph Pemberton had laid out an urban plan anchored by scenic geographical features. He set the government administration buildings in a series of garden pavilions, popularly known as the “the birdcages,” in a downtown Victorian arboretum on the shore of James Bay, and laid out adjacent suburbs, such as Rockland, as a series of picturesque country estates. Two Scottish-trained gardeners, John Blair and George Fraser, developed Beacon Hill Park through the 1890s. Previously Blair had been Commissioner of Parks for Chicago, and Fraser, who had studied botany in Edinburgh, went on to become one of North America’s most renowned rhododendron cultivators through his nurseries first at Sidney and then on the site of present-day Ucluelet.

Fraser and another nursery man, George Layritz, developed very successful businesses providing plant materials not only to burgeoning estate gardens of Victoria but throughout the West Coast and as far afield as Shanghai and Yokohama. A high point in the development of the city’s garden suburbs was the establishment of the exclusive Uplands Estates in the Victoria suburb of Oak Bay. This was a French capital-backed speculative real-estate venture designed by the renowned American firm, Olmsted Brothers. At the same time, the well-known Boston firm, Brett and Hall, was laying out Hatley Castle, James Dunsmuir’s country estate in Colwood, on a lavish scale.

Into this milieu in 1906 stepped two Japanese immigrants from Yokahama, Yoshijiro Kishida and Harry Takata. They commercialized the idea of the garden attraction by constructing a destination Japanese tea garden at the termination of a street car line on the Gorge Inlet. Yoshijiro brought out his father, Isaburo, a trained horticulturalist and garden designer to design the tea garden in an authentic manner. The tea garden was an immediate success and Isaburo Kishida garnered further local commissions, one for James Dunsmuir’s Hatley Park Estate and another for Jennie Butchart’s public garden enterprise at Brentwood in Saanich. The Dunsmuir and Butchart gardens remain, both stroll gardens carefully integrated into the “borrowed” natural landscapes — hallmarks of the traditional Japanese garden. With the Second World War internment of the Takata and Kishida families, the Gorge Tea Gardens were closed and destroyed by vandalism and the forced sale of plant materials and building components. Recently, prompted by the Canadian Japanese Reconciliation Agreement, the Takata Gardens have been recreated, and are finally now under reconstruction.

Tunnard, growing up in an Oak Bay home on Pleasant Street, would have been in the midst of all this. English immigrants, the Tunnard family would have easily integrated into Victoria society giving Christopher plenty of inspiration for his later career. And he was not forgotten. In 1970, the successor to Victoria College, the newly-formed University of Victoria, gave one of its first honorary degrees to its former student and native son. And as if to complete the circle, Lawrence Halprin, the San Francisco landscape architect who developed the landscape scheme for the University of Victoria’s Modernist Gordon Head Campus, had studied under Tunnard at Harvard. It is perhaps not surprising that Victoria would produce one of the most important and influential landscape theorists of the 20th Century.

Treib, a professor emeritus at the School of Environmental Design, U.C. Berkeley, has a made an important contribution to the history of landscape architecture. The focus on the early work of Tunnard set in comparative context with the parallel career of Sutemi Horiguchi provides quite a different perspective from that of the earlier biography of Tunnard (David Jaques and Jan Woudstra, Landscape Modernism Renounced, 2007).

As designer, editor, and often photographer, Treib presents the biographical accounts as a series of well- organized sub-chapters in which he frankly recognizes the research and attribution difficulties caused by the paucity of design documentation and the fact that very little survives of the built projects of either man. Footnotes are minimal but informative, the bibliography extensive, and the index more than adequate for cross referencing the two stories. With this book, Treib has a made an important contribution to the history of landscape architecture.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. His most recent publication, concerning the Modernist architectural heritage of Victoria (1935 1975), Conservation Guidelines for Modernist Architecture in the Victoria Region (2020), is available in a free on-line digital version. Martin currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia and for Government House, Victoria. Editor’s note: Martin Segger has reviewed books by Daina Augaitis, Allan Collier, and Stephanie Rebick, Leslie Van Duzer, Richard Cavell, Sherry McKay, Robert Ratcliffe Taylor, Darrin Morrison & Co., Greg Bellerby, Anne Whitelaw, Rhodri Windsor Liscombe & Michelangelo Sabatino, and Glen Mofford for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1028 Christopher Tunnard’s gardens”

ORO editions just sent me the link to the review of my book on Christopher Tunnard and Sutemi Horiguchi. I would like to thank Martin Segger for such a deep and thoughtful review—and for providing information about gardens in and around Victoria that I wish I had known about before writing the book. Please send his email. Thank you

Thanks, Marc. Martin has indeed written a captivating review of your important book about these major landscape architects, one of whom, Tunnard, has been largely forgotten in his native city and province. Martin’s review has brought a lot of traffic to the Ormsby Review, so I’m grateful to both author and reviewer! I will send you his email address in a separate message.