1013 Coast to coast with the CPR

Railway Nation: Tales of Canadian Pacific, the World’s Greatest Travel System

by David Laurence Jones

Victoria: Heritage House, 2020

$34.95 / 9781772033496

Reviewed by Ron Verzuh

*

Riding the Rails into Canada’s History: Illustrated anecdotes offer famous and lesser-known stories about the CPR.

Riding the Rails into Canada’s History: Illustrated anecdotes offer famous and lesser-known stories about the CPR.

We can still hear the distant call of a diesel engine’s whistle today in most regions of Canada and for many of us it is a sound that transports us to an earlier time, a romantic past that lingers. Most likely it is a Canadian Pacific Railway train clickety-clacking in and out of our lives, as Railway Nation author David Laurence Jones so glowingly recounts in this anecdotal history of Canada’s great continental iron horse.

It is part of our collective heritage, as famous writer Pierre Berton taught us in The Last Spike, CBC showed us in The National Dream, and songwriter Gordon Lightfoot sang to us in his Canadian Railroad Trilogy.

We find the CPR in the most obscure corners of our history as it linked the country together with a dual ribbon of steel that assured our nationhood. Indeed, it is part of our national DNA. And Jones, a former CPR employee, invites us to join him in an exploration of the legendary railway from its Hollywood image in films like Canadian Pacific with Randolph Scott and Jane Wyatt to stories of the daring rail builders now lost to history.

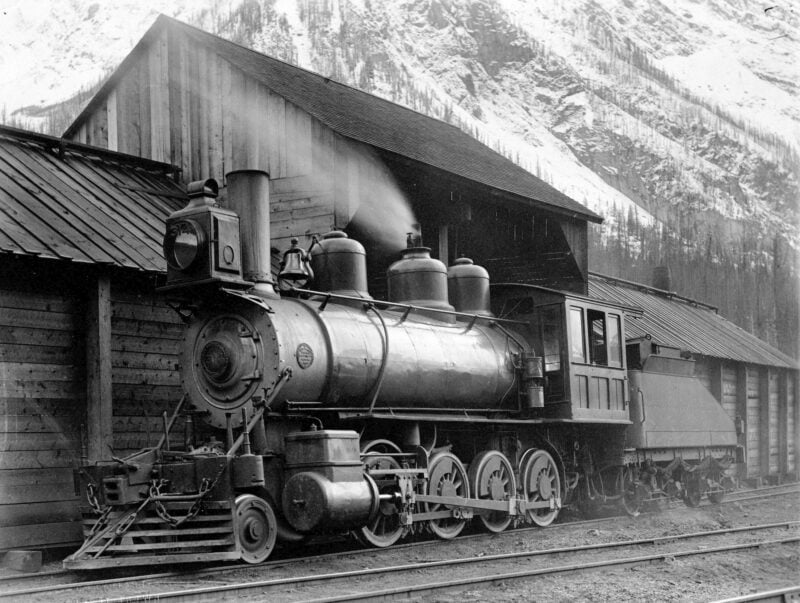

CPR bosses like founding builder William Cornelius Van Horne and company president Thomas Shaughnessy get plenty of coverage in Railway Nation. But Jones also gives credit to the navvies (rail workers) who performed the daily drudgery of building and later running a railway.

Mostly Jones chooses anecdotes, about 60 of them, to twig our CPR memories or more often to remind us that the railway was part of our ancestors’ lives in so many ways. In many cases, they might not have set foot in the New World without it. It was the CPR that hired overseas recruiters to entice refugees from war-ravaged Europe to migrate to Canada on CPR ships and trains.

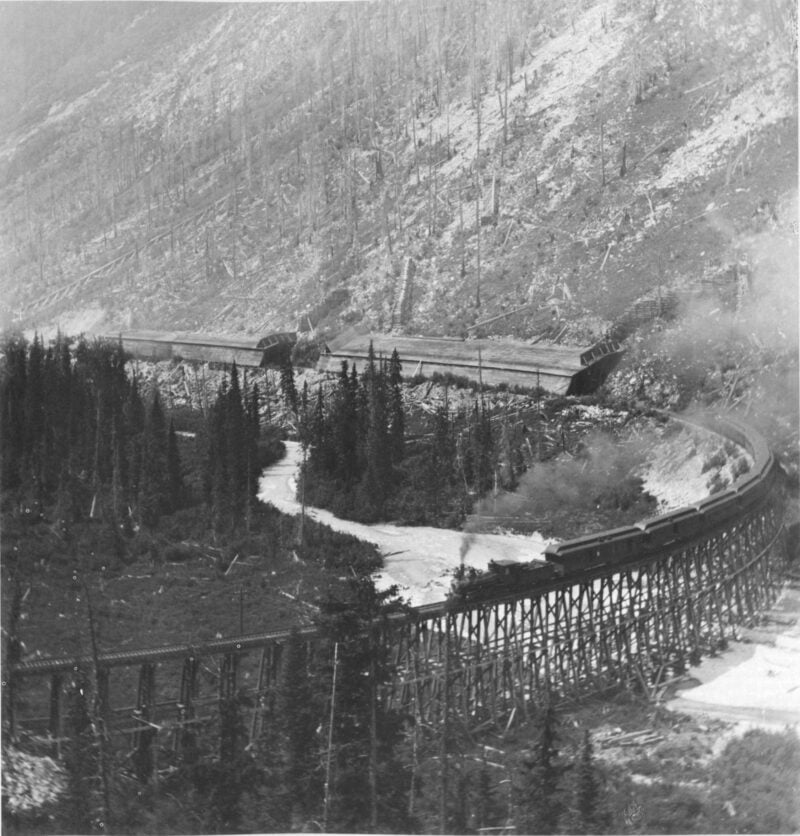

Trainspotters and train historians get a healthy dose of technical detail from Jones, including much-celebrated engineering feats like the “notorious Big Hill” at Kicking Horse Pass and the Connaught Tunnel, an “engineering marvel” in BC’s Selkirk Mountains.

In “Vamoose Caboose” we all get a refresher lesson on the car with the unmistakable pop-up tower that was once coupled to the end of the train.

The CPR in wartime conjures many tales of the role the railway played in assisting the Allied Forces. It also allows Jones to mention the role of the women who took on many jobs previously designated male-only positions. They filled them “quite adequately,” Jones notes.

Delivering the mail, transporting the Montreal Canadiens, and introducing royalty to its Dominion subjects, it was all part of the CPR’s legacy. Other distinguished riders included Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a keen seeker of the elusive black bass in Northern Ontario.

If its main competitor, the Canadian National Railway, was the “People’s Railway,” the CPR was the profit-motivated engine to secure Canada’s future as a capitalist nation. Along the way, it brought dental cars to remote parts of Canada, ensured that patients got rushed to hospital, and provided some communities with a car outfitted as a schoolroom.

The corporation has its unsavoury historical moments as well. To his credit, Jones does not shy from mentioning some of them. One example is its treatment of the Chinese workers who were instrumental in blasting a rocky path through western mountains. As Jones notes, they received half the pay and got the most dangerous assignments.

Some eastern and southern European immigrants were also exploited to enrich company shareholders, and Indigenous people were shoved aside as the CPR helped newcomers seeking a new future to settle as homesteaders. Historians may also debate the CPR’s role in quelling the Riel Rebellions and helping authorities end labour disputes. But Jones does not dwell long on these questions.

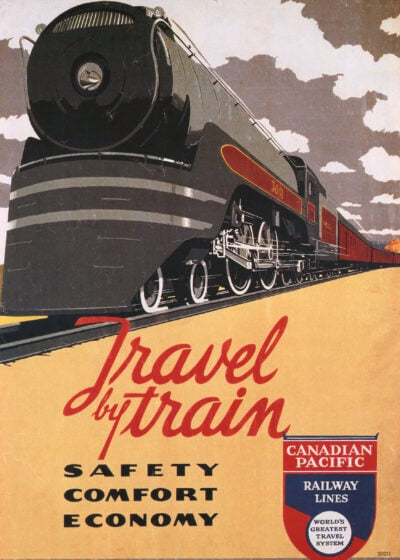

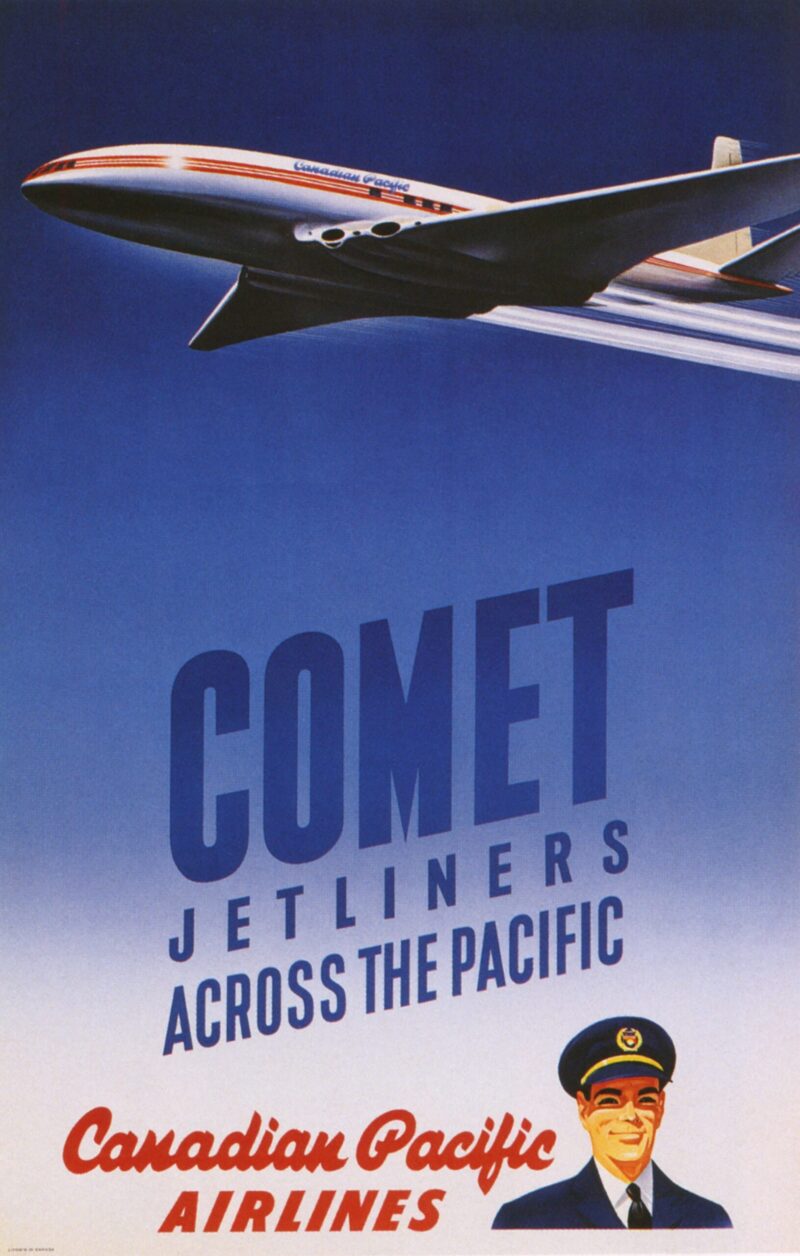

Railway Nation is enhanced by photographs that adorn almost every story in the oversized book, and they add colour to the telling of one of our great historical adventures. Poster images include CPR resorts in the majestic Rockies at Banff and Lake Louise; landmark hotels in most major cities, including the Vancouver Hotel, Victoria’s Empress, and Quebec City’s Chateau Frontenac. They also promoted the luxury of a CPR sea voyage and the speed of an overseas flight. All largely matters of history now, but Jones salts our interest anew in the “World’s Greatest Travel System.”

Looking at the old black and white photos and learning about the lesser-known history of this storied railway, I think back to when I was a kid standing on the track siding in a little village in the Kootenays. The CPR engineer would wave from his window as he rounded the next bend. Under his metal wheels, he left me a flattened shiny penny as a souvenir. I will never forget the experience.

*

Ron Verzuh is a writer, historian and documentary filmmaker. His personal experience with the CPR is not directly associated with its role as a railway, but rather with its purchase of a giant smelter at his birthplace of Trail, BC, in the late 1890s. Eventually it became known as Cominco and his family among so many others amassed a combined seniority of more than 80 years there. Editor’s note: Ron Verzuh’s recent contributions to The Ormsby Review include reviews of books by Gary Steeves, Ian Haysom, John O’Brian, Scott Stephen, Christine Hayvice, Keith Powell, Norm Boucher, and Ron Shearer.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1013 Coast to coast with the CPR”

Dear Mr. Jones: I didn’t claim that the Chung collection is superior to the Glenbow nor the CPR corporate collection. I wrote it “rivals.” You state, when he visited the CPR archive, “His main interest was in Chinese immigration to Canada and the role CPR had played in facilitating that.” That may be so. However, and more importantly, the Chung Collection at UBC is much, much more than just a representation of Chinese workers who helped build the railway through the Rockies. What can be discovered in the collection with respect to the building of the railway, however, is that the Chinese work ethic shamed the often lazy and frequently hung over contract workers who were sometimes too timid to take on dangerous blasting assignments, the result of which were many deaths. These historical facts are drawn from manuscripts, correspondence and vernacular photographs. The Chung collection is enormous in its holdings (over 25,000 items, including a vast trove of CPR related material), not just for the CPR’s operations across Canada but also for the role of the Empress ships, since inception. What can be seen in the Chung museum gallery is a very small fraction of the full collection, with only a small but significant representation of the role of the Chinese railway workers. Over more than six decades, Dr Chung salvaged important corporate documents discarded or abandoned during CPR office clear outs in Vancouver, the Montreal Windsor Station and elsewhere. Booksellers and antique dealers from across North America sold him all kinds of CPR pamphlets, photographs, albums, vernacular correspondence, posters, letters from officials and dignitaries, diaries from survey crews, full silver and porcelain table settings, and more. The Chung collection holds a unique and complete archive relating to the CPR immigration and colonization scheme, one centered around Rev. MacDonnell’s personal papers. Rev. MacDonnell brought a large group of Scottish immigrants to Clandonald, Alberta — an important way in which the Canadian prairies were populated, helped by the railway, and a source for CPR’s corporate profits. I presented Dr. Wallace Chung with a copy of Railway Nation as a gift, and asked if he had been consulted on what he might contribute or suggest. One of Canada’s most passionate collectors and knowledgeable authorities (with his own museum and archives), known to you, was not contacted for what he might have added to make the book more human (and eccentric) drawing from his comprehensive knowledge of his own collection, and the entire history of the CPR, so that Railway Nation could be more than a well written, beautifully illustrated corporate public relations history, assembled by a talented team of graphic designers. The subtitle “the World’s Greatest Travel System” alludes to the story of the Empresses, and the “highway” around the globe, yet even a short account of this is missing. I agree that the Encyclopedia of the Canadian Pacific would reach several weighty unreadable tomes, but to dismiss the Chung collection as consisting “mostly of items produced over the years by the CPR for promotional purposes” is to willfully ignore what any special collections librarian (or Dr. Chung) could have pointed to as any number of unique, and historically significant and important primary source materials unrepresented in either the Glenbow or the CPR archive. I am basically saying that a trip across the Rockies to investigate some of the unique holdings of the Chung collection with the help of the knowledgeable staff at UBC Rare Books and Special Collections (investigating what you call primary sources) and to meet with Dr. Chung, or even to give him a phone call, could have made Railway Nation an historically better, and more factually inclusive book while still preserving the economies of scale for a popular book production. The book might also have included curious nuggets such as: many of the high quality railway ties used by the CPR were manufactured by German industrial steel firm Krupp (because those made in Canada or the US were faulty), or that Kaiser Wilhelm II was at one point one of the biggest shareholders of CPR shares in the world, a situation which changed when World War I made him and all of Germany an enemy. Respectfully, Bjarne Tokerud

David Jones didn’t consult the one archive that rivals both the Glenbow’s and the CPR’s. In certain areas, it is vastly superior to both of them. There is no excuse for not having accessed the nationally and UNESCO recognized treasure trove of CPR material housed in The Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection at UBC, much of it available digitally. Rich in CPR pamphlets, posters, documents, diaries, and historical photographs, a fuller human story drawn from the vast Chung collection might have been woven into a history that sometimes just covers corporate milestones. Strangely, Jones omits the role of the fleet of Empress ships that made the CPR the only “Highway to the Orient” where tens of thousands of tourists travelled around the world by sea (and across Canada by rail) on one commercial line. Numerous factual errors deflate the book’s credibility. Jones gets the story of ceremonial Last Spike wrong. It was neither “fancy” nor silver plated as Jones states. Made of hallmarked sterling silver by a Quebec silversmith, cast as an exact replica of a CPR spike, Lord Lansdowne, the highest representative of the Queen of England, wanted to present the ceremonial silver Last Spike to Cornelius Van Horne during the Craigellachie event, but was delayed in reaching the spot in time. Lord Lansdowne then had the spike hinged to a marble stand so that it could be used as a paper weight. The silver plaque on the side of the stand clearly states The Last Spike. Along with a very personal letter in Lansdowne’s hand, the spike and letter were sent to Van Horne, not to the Van Horne family, as Jones states. The Last Spike re-surfaced in 2011. The Museum of Civilization was too “cheap” to pay for the two professional appraisals necessary to certify the Spike and other Van Horne related historical artifacts as Canada Cultural Property of outstanding significance and national importance. The family had to cover the substantial appraisal fees. The substantial value given to the Spike and other items were ultimately certified by CCPERB. If there ever was a symbolic artifact that represents the unification of Canada as one nation, I believe this is it. And yet, within the Canadian Museum of History, it languishes as a thinly described digital artifact, mis-catalogued and stripped of all its patriotic lustre.

Thank you for your well-documented comments. I appreciate learning more about the Chung Collection and will definitely access it in future. RV

Thank you for your comments, Mr. Tokerud. The Chung collection, as you say, is indeed a fine collection, but it is no way superior to the CPR’s own collection, nor that of the Glenbow. I was a good friend of Wally Chung, and worked as a staff member of the CP Archives when he was assembling his collection. His main interest was in Chinese immigration to Canada and the role CPR had played in facilitating that. As a result of his many years of collecting pamphlets, posters, documents, diaries and historical photographs, the Chung collection at UBC is an excellent source of information on this topic. Having had a thorough tour of the collection at the university led by Wally himself, I had occasion to use information from his collection in stories I wrote for some of my earlier book projects. For Railway Nation, however, I used mostly primary source material, whereas the Chung collection consists mostly of items produced over the years by CPR for promotional purposes.

I have written several other books about various CPR subjects, some of which include stories about the Empress ships. With CPR’s long and rich history, a book including all of its involvements would be encyclopedic in length, so I have chosen to present my offerings in shorter anthologies, incomplete as they may be for those seeking all-encompassing chronologies.

As for my apparent mistake in suggesting that Lord Lansdowne’s silver spike was plated rather than sterling silver, I thank you for correcting me. I’m sorry I lost all credibility with you as a result of my error, but it is very difficult to be absolutely one hundred per cent correct in a book that incorporates hundreds of facts, no matter how thorough the research. Mea culpa.