#946 Inside the Iranian Revolution

Aria

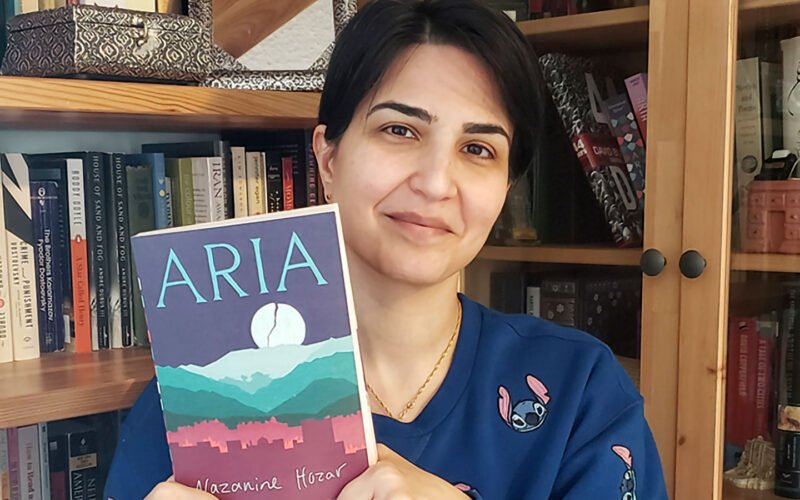

by Nazanine Hozar

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Knopf Canada)

$24.95 / 9780345811820

Reviewed by Candace Fertile

*

On March 12, 2020, Hozar’s Aria was one of five books shortlisted for the 2020 Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize of the BC and Yukon Book Prizes — Ed.

*

Nazanine Hozar’s debut novel tackles the chaos of Iran from 1953 to 1981 by focussing on the life of its title character, Aria. Abandoned as a newborn under a mulberry tree by her mother Mehri, who fears the baby’s father will kill her, Aria is found by a man who takes her home to his wife. While the baby is saved from death in the freezing Tehran night, her childhood is full of abuse from her new mother Zahra.

Nazanine Hozar’s debut novel tackles the chaos of Iran from 1953 to 1981 by focussing on the life of its title character, Aria. Abandoned as a newborn under a mulberry tree by her mother Mehri, who fears the baby’s father will kill her, Aria is found by a man who takes her home to his wife. While the baby is saved from death in the freezing Tehran night, her childhood is full of abuse from her new mother Zahra.

Hozar’s cast of characters is vast although each one has an effect on Aria, and to some degree is affected by her. The third person point of view shifts from character to character and through time and place in a somewhat incoherent manner, perhaps mirroring the turmoil facing individuals and the country. But as a narrative strategy, it can be confusing. It also helps if readers have some knowledge of Iranian history during this time. Hozar was born in Tehran and moved to Vancouver as a child. The novel is historical, not autobiographical. And it appears that Hozar tried to cram in as many examples of the suffering the Iranians endured, no matter what their belief system or economic status.

Conflict is the essence of this novel: conflict between rich and poor, male and female, Christian and Muslim, radical and moderate Muslim, Shah and Khomeini, and many others. And the conflict is inevitably matched by violence. While there’s no doubt such actions occurred, the novel feels overloaded and thus melodramatic, especially since the characters are largely ciphers for the ideas Hozar is exploring. The one character who seems the most human is Behrouz, the driver for the army who rescues Aria and names her. His wife hates him and hates the child. Zahra is older than Behrouz and already has a grown son out of wedlock, and he marries her because his father pressures him to hide his homosexuality. Behrouz’s job takes him away from home for days on end, so he cannot protect Aria. They are poor, but it’s unclear why Zahra is so mean to the child. That Behrouz turns to opium is completely understandable as his life has so little joy.

But Aria’s motivation is not evident. She is a creature of extremes, sometimes kind, but mostly quite nasty and volatile, often working against her own self-interest. Perhaps because of Zahra’s ill treatment, poverty, or just her own personality, Aria lashes out verbally and physically at the world. Emotionally she is all over the place, and it’s impossible to get a handle on her. Because she is such a mass of contradictions, her lurching from mean or stupid action to another is sort of believable, but it gets tiresome. She is capable of kindness, and she does occasionally question her own erratic behaviour, but it wasn’t enough for me to feel moved by her situation other than as a general reaction to anyone in pain or causing pain. For example, after Aria burns a woman she is supposed to be helping, the narrator says, “Eventually her rage left her, and Aria became aware of the depth of villainy that had come from within her, without reason or cause.” That’s not satisfying.

Aria’s home life also demonstrates the divergence of Iranian society and its inequity. After early childhood with Zahra and Behrouz, Aria is taken in by Fereshteh, a wealthy woman whose baby had died years earlier. And Fereshteh’s husband had abandoned his pregnant wife to become an ayatollah. Once in the care of Fereshteh, Aria is able to attend a good school where she makes two important friends, Hamlet, who is Christian, and Mitra, a devout Muslim. They come from wealthy families, but Mitra’s father is constantly dragged off to prison for criticising the Shah. Hozar does an excellent job of showing the vast disparity between rich and poor. It’s clear that any society with such extreme difference cannot sustain itself when alternatives are offered to the poverty-stricken. The shift from the Shah to Khomeini demonstrates the adage, “Follow the money,” which is really all about power. And in Iran as in so many places, the people who suffer, the poor, continue to do so. And women whether rich or poor are controlled.

Education is a way to improve one’s life, but there still must be opportunities, first to get an education and then to use it. Basic literacy in any language is important in Tehran at this time, and a series of letters sets up a misunderstanding that has huge implications.

Overall, while I found the novel frustrating, it does give some insight into the challenges that faced and are facing Iran. But more focus on character development and more showing rather than telling would help. The language used is straight-forward, and the details of food and clothing help to breathe life into the narrative. The scope of the novel is ambitious, too ambitious, I think, especially when the connections between characters become too contrived to be believable. Aria’s birth mother reappears, and while it’s apparent to the reader long before it is to Aria, the narrative thread frays. Maybe it’s just that too many characters act irrationally. Or maybe it’s how people behave under extreme duress.

*

Candace Fertile has a PhD in English literature from the University of Alberta. She teaches English at Camosun College in Victoria, writes book reviews for several Canadian publications, and is on the editorial board of Room Magazine. She has reviewed books by Tiziana La Melia, Rita Wong & Fred Wah, Carla Funk, and Jen Currin for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#946 Inside the Iranian Revolution”