#942 West Coast Organic

House Shumiatcher

by Leslie Van Duzer, photography by Michael Perlmutter

Novato, California: ORO Editions, and Vancouver: UBC School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture [SALA] / West Coast Modern House Series, 2014

$24.94 (U.S.) / 9781941806616

*

Friedman House

by Richard Cavell, photography by Michael Perlmutter

Novato, California: ORO Editions, and Vancouver: UBC School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture [SALA] / West Coast Modern House Series, 2017

$24.94 (U.S.) / 9781939621672

Both books reviewed by Martin Segger

*

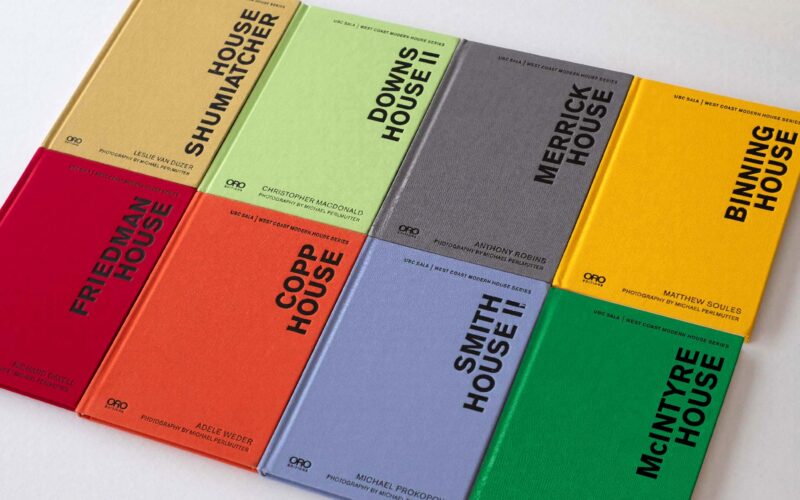

With this joint review by Martin Segger, we have now reviewed all eight books in the West Coast Modern House Series, a collaborative publishing venture between UBC’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and ORO Editions of Novato, California. In this review (below), Segger reviews Leslie Van Duzer’s House Shumiatcher and Richard Cavell’s Friedman House; previously he considered McIntyre House, by Sherry McKay. Hal Kalman reviewed four of the titles: Smith House II, by Michael Prokopow; Copp House, by Adele Weder; Downs House II, by Christopher Macdonald; and Merrick House, by Anthony Robins. Finally, Rhodri Windsor-Liscombe reviewed Binning House, by Matthew Soules. Michael Perlmutter was photographer in all the books. Enjoy! And, of course, thank you, reviewers. — Ed.

*

Giorgio Vasari, the 16th century chronicler of Italian Renaissance art, credited the Florentine artist Giotto di Bondone with laying the foundations of Renaissance design (disegno). Subsequent artists developed the style from this base, each setting themselves a problem (dificulta) to tackle. For instance, one Paolo Uccello, immersed himself in mathematics to resolve issues around the depiction of perspective. In fact, so much did this become Ucello’s obsession that Vasari wryly notes that he ended up “solitary, eccentric, melancholy and poor”!

It is tempting to caste these two books into something like Vasari’s framework. The 1953 Friedman House was designed by Fred Lasserre, particularly influential in West Coast Modern design as founding director of UBC’s School of Architecture, a position he held from 1947 to 1961. Lasserre was one of a small group of early West Coast architectural “Modernists” including B.C. Binning and Ned Pratt in Vancouver, and John DiCastri in Victoria, who pioneered the style.

The 1974 Shumiatcher House was the product of hat-maker turned engineer-cum-architect-developer, Judah Schumiatcher. Schumiatcher in this commission for his own family drew on his extensive experience in the trades and design to move the domestic house plan away from the tyranny of the 90-degree corner to experiment with the 120-degree splayed intersection, resulting in a much-improved expression of free-flowing space.

The Friedman house on Chancellor Boulevard near UBC, with its garden design by the equally pioneering landscape architect, Cornelia Oberlander, survives and has been diligently restored. The Schumiatcher house, alas, and perhaps partly because of its highly individual design eccentricity was demolished shortly after the family sold it in 2012.

Each of these hardbound pocket books, obviously benefitting from detailed attention by graphic designer Pablo Mandel, follows a presentation formula that has been consistent throughout this seven- volume ORO Editions series. Each book provides a short illustrated biographical and descriptive introduction to the commission, an extensive photographic essay, and a portfolio of schematic drawings including site and floor plans along with elevations. The resulting package is an easy read, concise and to-the-point but a keeper for ongoing reference. The set can also claim collector status on anyone’s bookshelf.

UBC media professor Dr. Richard Cavell introduces us to Lasserre’s clients, Sydney and Constance Friedman, founding faculty at UBC’s Faculty of Medicine, then provides a summary of the international background of Lasserre, and gives us a tour of the house and site. Indeed the site itself is significant in that the UBC Endowment Lands provided ample opportunity for many other trend-setting designer houses by Erickson, Thom, Downs, Pratt and others in the early post-war years. Experimental design was one result of the Endowment Lands remaining independent of Vancouver zoning controls.

A variation on the split-level formula, both the exterior and interior of the Friedman house made extensive use of cedar plank. Spatial organization is essentially a post-and-beam open plan, integrated with its garden setting through the skillful integration of glazed curtain walls, screened decks and patios. The plan features a series of communicating rooms flowing through the house and the garden. This formula, in varying degrees of sophistication, would literally become generic for Vancouver subdivision development through the 1960s and beyond.

*

If the Friedman house is essentially a glorified garden pavilion, the Shumiatcher house is a belvedere. In the essay, Leslie van Duzer provides an erudite but very readable commentary. Judah and Barbara bought the steeply sloped site in West Point Grey (and its 1910 bungalow) for its views, waiting seven years before demolishing the old house to build their own. Essentially a series of stacked asymmetrical intersecting pentagons project from an open multi-level core so as to afford a dramatic series of views and vistas out over Howe Sound while effectively screening out the immediate neighbours. An equally complex system of trellised deck extensions and sun screens mediate enclosed and open spaces.

Shumiatcher’s training and experience in all the constructions trades and the fact that he was client, architect and builder, allowed for a personalization of the design as well as a hands-on approach to execution. Finished in untreated western red cedar, inside and out, the interior featured meticulously crafted built-ins: bookshelves, cabinets and bench-nooks most of which the architect built himself. Perlmutter’s photographs, luckily and with some foresight, captured before demolition and while the Schumatchers were still in residence provides an intimate almost multi-sensory experience of the house as lived-in: glimpses of the furnishings, detailed cabinetry, art, wall-hangings — even kitchen-ware.

With the passage of time the structure was allowed to naturally mellow: the cedar exterior greying, the interior warming into red-tones of the western cedar boards. A double page spread in the essay and seven pages of detailed schematics in the back section are essential to an understanding of house and how the living spaces work. If one can image it, the overall result is a West Coast Modern arts-and-crafts interpretation of a Romanic English Gothic-Revival folly rationalized by proportional systems pioneered in Bramante’s Tempietto.

Both van Duzer and Cavell spend considerable time providing the intellectual context for the designs, thus we also get a good overview of West Coast Modern as a distinctive architectural style. In particular they both note the ancestry of the Modernism, in particular its European roots. Lasserre was a Swiss born internationalist, having studied in Toronto and Zurich then worked for a number of years during the 1930s in London. Calgary-born Schumiatcher cut his teeth as a businessman running his family’s Smithbilt Hats factory there, then combined a career as a developer and contractor while studying electrical and mechanical engineering in Edmonton and Toronto, and later architectural studies again at Toronto before graduating from UBC in 1966. A “renaissance man” in the world of design/build! Barbara and Judah internationalized their architectural taste and knowledge through extended travel sabbaticals: through both Europe and the United States and practicing variously in Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver.

Cavell sketches the international context for the style itself, noting in particular connective roots to European Modernism, particularly to the arch-functionalist Le Corbusier, the stripped-down essentialism of the German Bauhaus via the influential writings, work and also occasional lectures in Vancouver by the California-based Austrian immigrant, Richard Neutra. Neutra had trained in Vienna, studied with Adolph Loos and worked in Switzerland before moving to the USA in 1923 where he worked briefly for Frank Lloyd Wright before joining a former fellow student from his Vienna and Berlin days, California based Rudolf Schindler.

Despite these connections to “Modernism,” and the fact that the term West Coast Modern Style, has become deeply embedded in academic and popular architecture vocabulary perhaps we should at this point “interrogate” the term Modern in this context. After all, “modern” means “now.” And the West Coast Modern Style is now history! Neither authors downgrade the American roots of the style, particularly through the hands of Frank Lloyd Wright who so profoundly influential western American design in the 1940s and 50s, in particular Wright’s insistence on privileging geography of place in generating both design and materials. This “arts-and-craft” design ideology, rooted the cultural nation-building architecture of Henry Hobson Richardson, Louis Sullivan, the Chicago School, was expressed in domestic building design as “the shingle-style.” Cavell points out the debt Schumatcher owed, and acknowledged to Wright’s experiments with his Usonian house-type.

This arts-and-crafts American vernacular, with its emphasis on fit of the building in the landscape and use of regional materials, particularly coastal cedar and fir, already had a rich design tradition in the Pacific Northwest, especially British Columbia, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries’ work of Francis Mawson Rattenbury, Samuel Maclure, Thomas Hooper and others. It was popularized by the bungalow suburbs that built out Edwardian cities on both sides of the border. Maclure’s ground-hugging shingle-clad bungalow designs featuring extensive use of porches and verandahs echo Wright’s prairie-houses emulating the same aesthetic.

In this respect it should be noted that Wright went to some lengths to avoid the word “modern” with reference to his work, instead much preferring the term “organic,” i.e. in harmony with humanity and nature. In reality this was a far cry from the Corbusier’s famous dictum, that “The house should be a machine for living in,” or the serial cubist boxes produced as for worker’s housing in Berlin by Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius. Ultimately of course it was the Bauhaus circle, Gropius, Marcel Brauer, Meis van der Rohe, Erich Mendelsohn and others who fled the Nazi regime, relocated to the USA and assumed influential teaching position in schools of architecture across the United States. One result was the near wholesale adoption of the stripped-down machine produced design aesthetic of the International Style by the eastern American business elite, now sometimes more aptly referred to as the “Late Capitalist Style”!

Wright set up his own independent teaching “ataliers,” Taliesins East and West. Victoria’s Samuel Maclure had corresponded with Wright. A more serendipitous connection is F.M. Rattenbury’s in that his son, John, trained as an architect under Wright at Taliesin West and ultimately became its principal after Wright’s death. Victoria modernist John Di Castri, who trained under Wrightian disciple Bruce Goff at Oklahoma, undertook a grand tour of the United States to visit Wright’s major projects, and meet the master himself at Taliesin West. Shumiatcher also went to great lengths to meet Wright in New York in 1953 on the building site for the Guggenheim Museum.

This considered, perhaps West Coast Modern should more accurately be known as “West Coast Organic.” This term certainly captures the essence of the Shumiatcher and Friedman houses, and the others covered by this fascinating series of little architecture books.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. His most recent publication, concerning the Modernist architectural heritage of Victoria (1935-1975), Conservation Guidelines for Modernist Architecture in the Victoria Region (2020), is available in a free on-line digital version. Martin currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia and for Government House, Victoria. Editor’s note: Martin Segger has reviewed books by Sherry McKay, Robert Ratcliffe Taylor, Darrin Morrison & Co., Greg Bellerby, Anne Whitelaw, Rhodri Windsor Liscombe & Michelangelo Sabatino, and Glen Mofford for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#942 West Coast Organic”

I’ve really been enjoying these reviews of the monographs. The photos of Barbara and Judah’s wonderful house give me pangs — the locus for so many events, dinners, conversations. And now gone.