#899 Vancouver apologizes

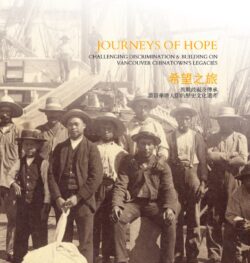

Journeys of Hope: Challenging Discrimination & Building on Vancouver Chinatown’s Legacies, by Henry Yu; edited by Sarah Ling, Szu Shen, and Baldwin Wong; translated into Chinese by Szu Shen

Vancouver: UBC Initiative for Student Teaching and Research in Chinese Canadian Studies, 2018. Distributed by the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of British Columbia

$50.00 / 9780993659317

Reviewed by May Q. Wong

*

April 22, 2018 was a momentous day for the City of Vancouver and Vancouver’s Chinatown, for City Council chose to hold its meeting outside City Hall, and in the heart of Chinatown, to deliver a formal Apology for past systemic discrimination against people of Chinese descent. To commemorate this occasion, Henry Yu, a professor in the Department of History at the University of British Columbia, compiled the coffee table book Journeys of Hope: Challenging Discrimination & Building on Vancouver Chinatown’s Legacies.

April 22, 2018 was a momentous day for the City of Vancouver and Vancouver’s Chinatown, for City Council chose to hold its meeting outside City Hall, and in the heart of Chinatown, to deliver a formal Apology for past systemic discrimination against people of Chinese descent. To commemorate this occasion, Henry Yu, a professor in the Department of History at the University of British Columbia, compiled the coffee table book Journeys of Hope: Challenging Discrimination & Building on Vancouver Chinatown’s Legacies.

The book does three things: it tells succinctly the story of the early Chinese immigrants, their fight for equality and justice, and their role in Vancouver, British Columbia, and Canada; shows how the City of Vancouver, since its incorporation in 1886 until the 1970s, used legislated as well implicit tactics to support white supremacy, which highlights the significance of an apology; and it introduces steps for reconciliation and to gain a UNECSO designation of World Heritage Site for Chinatown. The book is written in English and Traditional Chinese (I assume this was a gesture of respect to the early immigrants who learned Chinese before it was simplified in the 1950s by the People’s Republic of China). Photos of Chinese in British Columbia range from the 1880s to the events of April 22, 2018. A map showing the unique destinations and numbers of Chinese by Canadian province between 1910 and 1923 particularly interested me (p. 26).

Yu notes that Chinese migrants arrived “in 1788 in the unceded territories of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations at the moment that the first British arrived, on board the same ship. Cantonese carpenters that were picked up in Macau built the first fort, and the first local vessel so the British could trade along the coast” (p. 27). Like so many of the first Europeans to come to the province, the Chinese were lured by the 1858 Fraser River Gold Rush, many via the California gold fields. While some dreamt of finding the “mother lode,” others came to open businesses to provide food, supplies, and services. “They also helped build the logging, mining and farming industries in British Columbia, and established small businesses across Canada,” states Yu, and that “Chinese migrants followed gold rushes all around the Pacific, giving places like California, Australia, New Zealand, British Columbia, and the Yukon the name ‘Gum San’ (Gold Mountain)” (p. 20).

British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871 with a promise from the Dominion government that a railway would be built to connect the new province to the rest of the country. Chinese workers were specifically recruited in the tens of thousands, continues Yu, to help build “the difficult western portion of the trans-continental railway, suffering injury and death in numbers far beyond those of other labourers” (p. 21). While this transportation system “enabled the mass migration of Europeans to the province,” (p. 27) the new provincial government disenfranchised the Chinese (as well as the First Nations Peoples) in 1872. When the railway was completed in 1885, a $50 head tax was imposed on Chinese, and only Chinese, migrants. This amount was raised to $100 in 1900, and to $500 in 1903. Over the next four decades, until 1923, over $22 million would be raised through this tax, revenue that was shared between the British Columbia and federal governments.

Yu notes that the Act of Incorporation for the City of Vancouver (1886) effectively:

… disenfranchised people of Chinese descent (and the First Nations Peoples) from voting in municipal elections. The disenfranchisement not only meant losing the right to vote, but also effectively prohibited Chinese people from running for public office, studying for or entering certain professions [including law, medicine, dentistry, teaching, and pharmacy], and owning properties in some areas of the city (p. 37).

City Council had actively lobbied for the federal head tax to be enacted and increased, and in 1923, the federal government, based on further lobbying efforts, enacted the Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the “Chinese Exclusion Act,” which effectively closed the doors to further immigration of Chinese to Canada until it was repealed in 1947.

City Council used other methods to limit various aspects of the lives of the Chinese, Yu continues, including “its ability to negotiate commercial leases and land grants to enforce [an employment] ban. All City contracts after 1890 contained a clause that prohibited contractors to use any Chinese labour” (p. 44). Trade licences and levies were imposed on “areas of commerce where Chinese were already highly successful [such as laundries, restaurants and vegetable peddling]”(p. 46). Vancouver City Council worked actively against Chinese interests: “Where formal legislation could not be enacted, the City used informal methods such as vigilantes, unwritten law, and selective targeting to curb Chinese business and employment opportunities” (p. 47).

The Chinese community did its own organizing and lobbying with the support of some White allies, including Alderman Helena Gutteridge, who “refused to support the motion to amend the City Charter to limit issuing trade licences to persons of ‘Asiatic extraction’ in 1938,” and “labour leaders who spoke out against the use of white supremacy to organize unions” (p. 52). As Yu notes, “[s]tories like that of Chinese Canadian veterans fighting for re-enfranchisement, that of the Chinese soccer team pushing racial boundaries to create an equal playing field, and that of Vivian Jung and her fellow student teachers challenging racial segregation at Crystal Pool remind us that in overcoming racial prejudice and discrimination, Chinese Canadians also helped to make Canada a better place” (p. 58).

On June 6, 2006, the government of Canada, under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, issued a statement of Apology for the imposition of the head tax and offered a symbolic monetary compensation to then-living payers or their surviving spouses, as well as funding to establish a legacy program. On May 14, 2014, Premier Christy Clark, on behalf of the BC Legislative Assembly, apologized for 160 historical discriminatory policies against the Chinese and established a legacy fund aimed at educational projects.

Perhaps in response to the Province’s actions that year, the City of Vancouver started looking at its historical role in discriminating against Chinese residents. In the following year, the Historical Discrimination Against Chinese People in Vancouver Initiative was started and a voluntary advisory committee established to “guide the process of researching the past and consulting with the community to gather ideas for next steps” (p. 70). The process and the resulting written report culminated in the special City Council meeting in Chinatown. It was particularly moving to see the number of Chinese veterans, many in uniform, in attendance. These men had fought for Canada against racism, despite personally facing that same discrimination in their home country.

A significant legacy project is the pursuit of a UNESCO World Heritage Site Designation for Vancouver’s Chinatown. Chinatowns in new settler nations like Canada, the United States, and Australia were established both as a means of building strength in numbers through mutual support and to afford protection from the growing anti-Chinese racism of the 19th century. Vancouver’s Chinatown, established in 1885, is one of North America’s oldest and Canada’s largest. It has remained in the same geographical area with intact infrastructure and the continuous history of a specific cultural community. Yu notes that while “a large number of the original Chinese who came to Vancouver were from a small area of the Pearl River delta in Guangdong Province, the last half century has seen ethnic Chinese of a wide variety of different origins” (p. 84), adding to Vancouver’s vibrant, international character. Yu also flags a longstanding history of mutually respectful association between Chinese migrants and First Nations, both of whom suffered from racial discrimination.

Finally, Yu suggests that “Chinatowns reflect both the constraining effects of white supremacy and the role of Chinese Canadians and other targets of legalized discrimination as agents of change in the overcoming of racism, a transformation that has made Canada and other similar nations more just and inclusive societies” (p. 91). These factors, and more, make Vancouver’s Chinatown an exemplary representative of a people’s story of struggle, resilience, hope, and triumph.

*

May Q. Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. She is a graduate of McGill University, holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria, and retired from the BC Public Service in 2004. Her first book, A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (Brindle & Glass, 2012), concerns a Chinese couple separated for half of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel) concerns the diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to Victoria. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded face masks. Editor’s note: May Wong has also reviewed books by Mei-Li Lee, Catherine Clement, and John Price with Ningping Yu for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#899 Vancouver apologizes”

Very well done, May Q. Wong. Like all your work, this review is fair, factual, and entertaining.

As usual May Q. Wong writes with passion and excellence of research, along with factual historical and experienced moments from her own life. She overrides others’ lack of love and counters racial discrimination against people of all races and religions. May Wong is a treasure in our midst!