#887 A legend of British Columbia

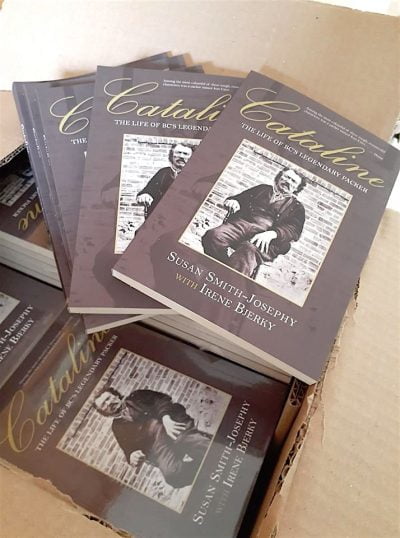

Cataline: Uncovering the Life of BC’s Legendary Packer

by Susan Smith-Josephy and Irene Bjerky

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2020

$22.95 / 9781773860244

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

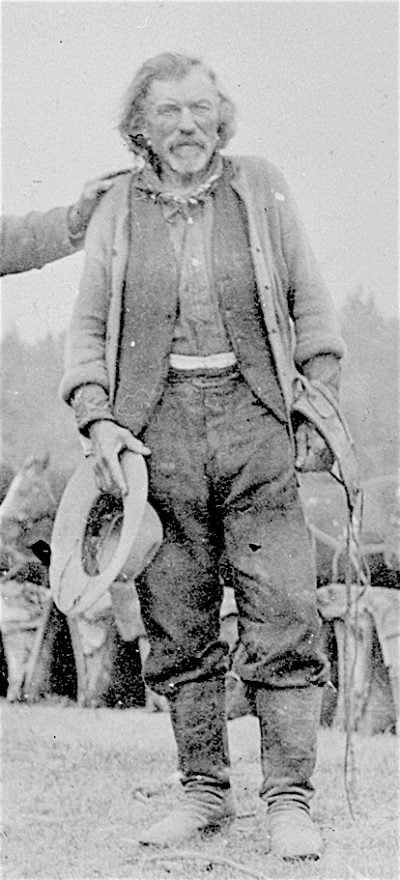

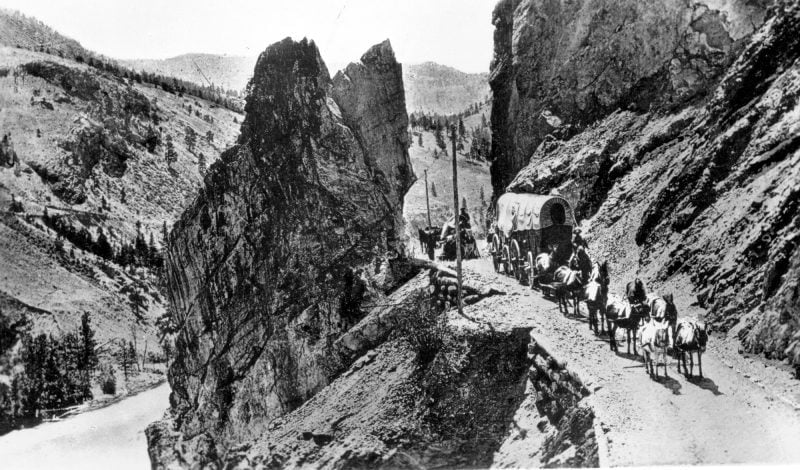

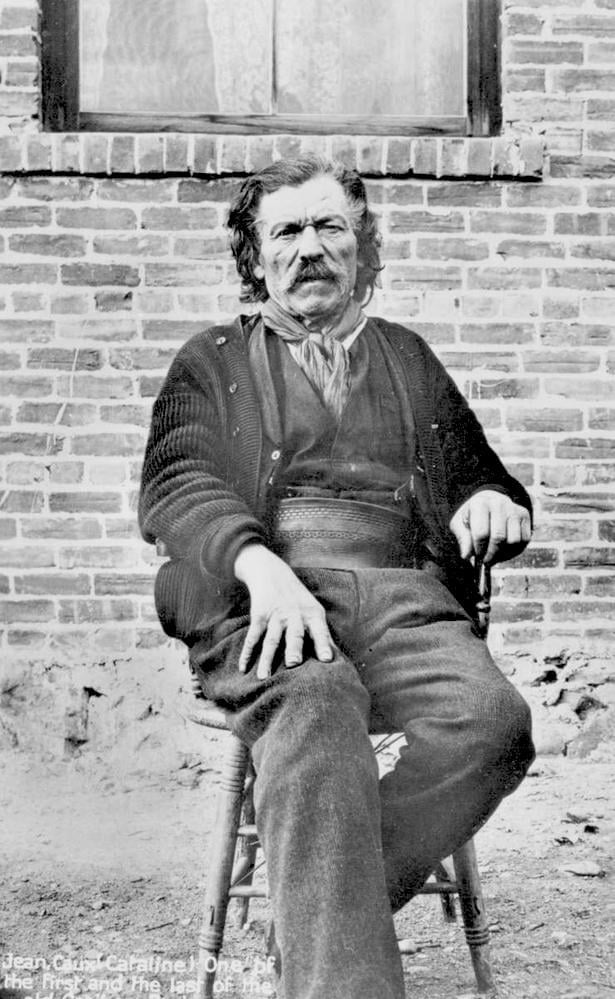

This is a book about the making of British Columbia by the simple hard work of carrying industrial material, strapped to the backs of horses and mules, across rivers, over mountain ranges, and through thousands of kilometres of bush for fifty years. It is billed as “the life of B.C.’s legendary packer,” Jean Caux, aka Cataline.

This is a book about the making of British Columbia by the simple hard work of carrying industrial material, strapped to the backs of horses and mules, across rivers, over mountain ranges, and through thousands of kilometres of bush for fifty years. It is billed as “the life of B.C.’s legendary packer,” Jean Caux, aka Cataline.

Caux’s determination and physical strength were astounding. The reasons for the nickname remain unclear.

The book presents a “life” in a very specific way. It is not a life as “the story of Cataline the man” but a story of “a way of life that Cataline lived.” There is a lot of legend here, such as this story of packing supplies for the Yukon Field Force as they tried to create a Canadian route to the Klondike, north from Telegraph Creek in 1898: “Cataline complained about the army’s incessant blowing of bugles as it upset his animals. “Alla time blowa de buga, scara de mule, no gooda.”

The story is told by Cataline’s friend Sperry Cline, and forms just one link in the long chain of anecdotes that brand Cataline as a man almost without language, or whose language was almost incomprehensible, a series of observations the book appears to take as “true.”

Is it? What would cause a man to have no comprehensible language? Nothing in Caux’s own life, as far as Cataline presents it. Possible explanations would be either some failure of memory, some form of alternative cognitive processing, improper language acquisition (perhaps due to deafness?), or some physical disability of throat and tongue.

His memory, however, was prodigious. His ability to manage complex organizational tasks and to attend to fine details of husbandry was beyond the normal range. Deafness was never mentioned, nor was any kind of physical deformation.

It is left as a mystery.

For the lack of any evidence in the book, I think this tic is simply an anglo-centric 19th century story-telling style picked up from novels mocking continental Europeans and colonials in the name of local colour, and dumped on Caux’s head. I say this because I am from British Columbia. I know the place a bit. I come from an immigrant family. My family name remains unpronounceable. Fifty years ago, it could not even find its way off anyone’s tongue.

If this book were a history, it might have explored these possibilities and unravelled the difference between Caux the man and Caux the legend. The legend is a story told by others, to delight their own audiences, and reflects as much on them and their cultural assumptions as on its subject, in this cause Caux.

That is fascinating. The book is full of fascinating moments and presents a story of British Columbia that has been largely hidden for a century and a half.

Nonetheless, it escapes my understanding why comments on incomprehensibility would go unchallenged in a British Columbia made up of at least a hundred ethnicities, and which has now transformed itself into a world diaspora built on ideas of mutual respect. I also wonder whether it is helpful to publish a work that does not actively strive to untangle this cultural tic.

What I can say is that Caux came from the mountains in the North of Spain, where he spoke a little-known dialect. Over the years, he encountered other immigrants from his region, and seemed to speak to them just fine.

The book does not connect these dots, yet its stories of Caux’s eccentricity and his incomprehensibility are repeated continually. What Cataline presents is exactly what it promises: a legend. Two legends, rather: The Legend of British Columbia, and The Legend of Jean Caux.

The British Columbia of the legend is a heroic place in the making. The British Columbia of Caux’s 19th century, on the other hand, was very much a place in the unmaking at the same time, a native space being redrawn into a Euro-american model. Cataline focusses on the hard work of the conversion. There is little mention of native people themselves, even though Caux lived much of his life with them and among them.

The Legend of Jean Caux is just as strong. Caux was everywhere, from Victoria to Hazelton, and from his ranch at Dog Creek to Telegraph Creek, Dease Lake and Stuart. He carried British Columbia out into native space. Such an oversized contribution to British Columbia is deserving of honour that the warm hagiography of this work doesn’t match.

I miss that: the native struggles and hardships that Caux packed through in all those years, for instance, or some acknowledgement of the native context of his claiming Secwepemc land in Dog Creek, or some comment on the immense class privilege behind the administration of law in the province.

The story is there. In 1872, Caux was being sued for damages in Richfield, in the Cariboo gold fields. The case has threads drawn from another story, and although the corresponding dates are unclear due to a muddy paragraph, the paragraph does appear to note that Judge Mathew Baillie Begbie went north to hear the case, sensibly enough. The paragraph also mentions a petition to preempt Caux’s ranch, because Caux was not a Canadian citizen. Those were the purported reasons anyway. It may have been that these were two separate trips, or it may have been the same trip. At any rate, the story is presented that in supposed repayment for Caux’s support of Begbie early in the judge’s career, Begbie stopped by at Cataline’s on the way, held an impromptu court, swore him in as a citizen, and then used his citizenship to dismiss the pre-emption case.

This fascinating view into how the law was being tested, used, and abused on many fronts is summed up in the book as follows: “It would seem that Begbie had remembered that long-ago day when Cataline had been there to ‘standa by the judge.’”

There is no mention as to whether Caux’s relationships with the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem was or was not part of the story here. The date, a year after British Columbia’s integration with Canada and a complete upheaval of relationships to native land, suggests that an exploration of such connections might have born fruit and given us a Caux beyond the legend, as Wendy Wickwire does in her more masterful At the Bridge, about the relationship between James Teit and the Nlaka’pamux.

Every book has a context, an audience, and a place in the lives of people which, in some way somewhere between small and large, it influences and helps to direct. That lack of historical curiosity and that patronizing approach is not something I would like to see passed on. What you would like to see come from it, I leave to you.

As for Caux’s abilities (prodigious strength, enormous and unshakeable loyalty, inability to manage money, illiteracy, astounding courage, a gift for managing animals, near-perfect woodcraft), these are the legends of a child-like peasant, or perhaps Hercules or Atlas, or praise of a faithful but simple, illiterate servant out of some 19th century novel or fairytale.

It could also apply to a dog or a horse. Or a mule: “Cataline loaded the engine base, which weighed 560 pounds, onto the toughest and most ornery mule in his train, old “Sundaygait.”

It could also apply to a dog or a horse. Or a mule: “Cataline loaded the engine base, which weighed 560 pounds, onto the toughest and most ornery mule in his train, old “Sundaygait.”

It’s rather abusive, really:

Three weeks after leaving Quesnel Cataline unloaded the engine base at the 43rds workings at Dunkeld on Kildare Gulch. Sundaygait, relieved of his load, stretched his long length on the ground and lay there for 48 hours straight.

The book makes nothing of this astounding legend or the window it opens wide onto the past, but at least it records it and puts it into a timeline. But now what?

Are we just going to leave it at that, as Smith-Josephy does? I sure hope not. I hope we read her careful compilation of legends, roll up our sleeves, and get to the work of revealing the life of the man Jean Caux and of those he loved and worked among.

*

Harold Rhenisch was raised in the grasslands of the Similkameen Valley and has written some thirty books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys. His other grasslands books are the Cariboo meditation Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and the Similkameen orchard memoir, Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on his Cariboo-Chilcotin books published by Country Lights: Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as The Bowron Lakes (2006), and he writes the blog “Okanagan-Okanogan: One Country without Borders,” from his home in Vernon. For seven years, he has toured the grasslands of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho while working on Commonage, a history of the Okanagan region set in its American context, highlighting the American history of Father Charles Pandosy and situating the roots of the Commonage land claim in the North Okanagan in American colonial practice in Old Oregon. Harold lives in Vernon. Editor’s note: previously Harold has reviewed books by Bill Barlee, Fred Braches, Raphael Nowak, Karl Koerber, Norbert Ruebsaat, Ken Mather, Daniel Marshall, Barbara MacPherson, and David Pitt-Brooke for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “#887 A legend of British Columbia”

Judge Begbie may well have made Cataline a British subject, and, therefore, a candidate pre-emptor, but the “repayment” motive is improbable.

Both 19th century colonial and provincial governments paid considerable attention to the desirability of “aliens” as pre-emptors, sometimes forbidding them to apply, sometimes permitting to apply, upon making a promise to obtain British-subject status.

In the 1884 Land Act, the only 19th century Land Act I could find on the Internet today, the “welcome” the B.C. government extended “aliens” like Cataline — and the welcoming role, a statutory role, a magistrate like Begbie was required to play — reads this way:

“3. Who may record unsurveyed land … any alien making a declaration of his intention to become a British subject, before a Commissioner, Notary Public, Justice of the Peace, or other officer appointed therefor, … may record any tract of unoccupied and unreserved Crown lands….”

Ms Smith-Josephy and Ms Bjerky: thanks for writing this book. I am sending this notice to librarians I know. Richard: Thanks for assigning the review, and Mr. Rhenisch, thanks for reviewing.