#872 Making some good trouble

Disabled Voices Anthology

by sb. smith (editor), with a foreword by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Nanoose Bay: Rebel Mountain Press, 2020

$18.95 / 9781775301950

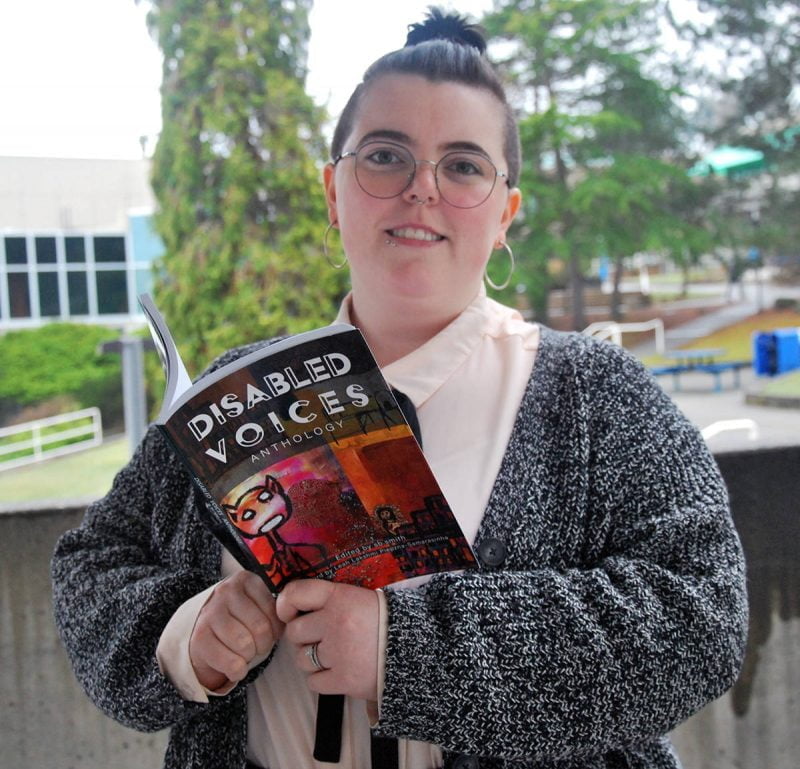

Reviewed by Margot Fedoruk

*

I want to see young people in America feel the spirit of the 1960s and find a way to get in the way. To find a way to get in trouble. Good trouble, necessary trouble. — John Lewis, American civil rights activist

I want to see young people in America feel the spirit of the 1960s and find a way to get in the way. To find a way to get in trouble. Good trouble, necessary trouble. — John Lewis, American civil rights activist

Rebel Mountain Press has come up with some winners of late, bringing a voice to those who are not always heard in mainstream literature, including the recently published Disabled Voices Anthology. This collection is part of a burgeoning genre dubbed “Crip Lit.” Disabled Voices is filled with stories and artwork from people with varying disabilities, both visible and invisible, touching on subjects from autism, accessibility, substance use disorders, to living with unrelenting pain, plus many more. The anthology contains a mixture of poetry, fiction, art, and non-fiction created by 28 disabled writers, activists, and artists selected from Canada, the US, and the UK with a detailed contributors’ biography in the back.

Editor sb. smith states that this book is written for a disabled audience: “Our inherent value lies in our existence, not our productivity, and our work is not compiled here to prove our worth to abled people. This is for us.” Even if you are not in the intended demographic, Disabled Voices will leave you feeling more enlightened about disability justice, and you may just find out the meaning of what it means to make good trouble.

Smith first met Lori Shwydky, founder and publisher of Nanoose Bay-based Rebel Mountain Press when she was doing a presentation about her island-based publishing company at Vancouver Island University. Smith had a dream to “amplify diverse Disabled voices” and thought an anthology would be the right vehicle. After the class, smith (who prefers to spell their name in lowercase) approached Shwydky, pitched the idea, and the project was born.

The foreword is written by Toronto-based Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, a disabled poet, performer and community activist of colour, who stresses the importance of “saving ourselves” and reminds readers of Price Ro’s words of wisdom, “power not pity.” Piepzna-Samarasinha also discusses the importance of hearing everyone’s reality, realities that are not always served up in everyday literature. Piepzna-Samarasinha’s publishing credits include Tonguebreaker (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019), “a survival handbook for working class disabled femmes of colour,” and Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice (Arsenal, 2018).

The anthology opens with a short poem by Eryn Goodman, a Vancouver Island resident with chronic lyme disease. The poem is about the cruel realities of using a cane as a teen, reminding readers that “three-legged, cryptid people of this world are no beasts.” The well-chosen accompanying artwork, titled “Cripple Punk Portrait #23” by Michaela Oteri is reminiscent of a vintage-style poster but with a modern-looking “punk” with a cane and spiked studded choker. The anthology also includes four more vibrant, expressive works of art from Oteri’s Cripple Punk Portrait series. Oteri, who also goes by the name of Ogrefairy, is an award-winning Florida-based digital artist whose ability to showcase people with disabilities with her distinctive art nouveau flair is a joy to behold.

Other artwork of note are Ace Tilton Ratcliff’s “Self-portrait #1” and “Self-portrait # 3.” These coloured photographs portray the artist offering up her naked, twisted, tattooed body to the camera.

“Blasphemy,” an essay by Bipin Kumar, is a call-out to the Indian Aunties who offer up unwanted advice about his disability. They tell him, “God will make everything better.” In response he rails, “I’ve been talking to people like you for a hundred years. You’re like a speck of dust talking to the Sun. I’m a god. Who the fuck are you?”

Other moments of insight emerge, including Nina Fosati’s “Spoons,” where a woman who is suffering from seizures and blood clots of the lungs says simply but powerfully, “My husband and I have a secret understanding, I will die first.”

Fosati’s other non-fiction piece, “Companions,” is a gentle account of her search for connection and experiences of living her life with constant pain:

Our jagged bones scrape and grind against each other. Our backs send searing pain with each movement. We try not to cry out, but the pain escapes as moans, sudden inhalations, searing hisses. We make the sounds people expect of the elderly.

The strength of Disabled Voices Anthology is its diverse mix of voices stemming from each contributor’s own unique life experiences and challenges. While many stories delve deep into the personal narrative, some essays are pure rallying cries for disability justice, such as Alice Wong’s “Valuing Activism of All Kinds.” Wong brings up important questions such as “who are your people?” and “what does it mean to show up for others?” In 2018, Wong compiled an anthology, Resistance & Hope: Essays by Disabled People: Crip Wisdom for the People (Kindle: 2018). Wong, an activist, journalist and founder of the Disability Visibility Project, has two pieces in the anthology.

In “HASHTAGGETLOUD,” Jill M. Talbot uses a stream of consciousness style of storytelling in her fictionalized account of homelessness and addiction. The main character is a young bipolar girl who says:

I was less alone in the gutter than I am in front of you folk with your #GETLOUD campaign who want me to be as quiet as a mouse, with your art and your poetry and your hypocrisy.

The book has an easy-to-read font, printed larger than normal to help those with visual impairment. There are also detailed content notes before many of the stories and poems, including profanity and other trigger warnings. These notes, while very thorough, often have the unintentional effect of stopping the flow of the reading experience. Some notes appear unnecessary, such as, “brief mention of food and description of minor sports injury.”

On the positive side, the terms in the content notes may prompt readers to search up the meaning of any terms, such as “ableism” which, according to Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary, means discrimination or prejudice against individuals with disabilities. Other key words to learn include “crip,” a slang term for being unable to use all your limbs, and “inspiration porn,” which was first used by disability rights activist Stella Young to describe people with disabilities as inspirational solely or in part on the basis of their disability.

Another benefit of these content notes is that they serve to signal the issues to be dealt with, such as Nicola Kapron’s reflective piece, “The Invisible Girl,” which carries the content note, “internalized ableism.” In her essay, Kapron explores her resistance to accepting her own multiple disabilities which include, among others, face blindness and topographagnosia, which is the inability to orient oneself to their surroundings. She explains:

I’ve finally begun peeling back the masks of normativity, which were uncomfortable and stuffy and never fit me properly anyway.

Similarly, as Lys Morton explains in his essay, “Community, Identity, and My Gifted Diagnosis,”

There is nothing wrong with being Disabled. There is something wrong with shame denying you the community and knowledge you need to survive and thrive.

Disabled Voices Anthology serves to illuminate new and diverse human experiences. Small indie publishers like Rebel Mountain Press are proving to be vital to the cause. For example, Rebel Mountain brought the world Michelle Sylliboy’s book of poetry, Kiskajeyi — I am Ready, which recently won the 2020 Indigenous Voices Award.

Now more than ever, in these complicated times of rising civil unrest combined with a welcome intellectual intersectionality, it is imperative to listen closely to the stories of those who may be marginalized. Disabled Voices Anthology will equip readers with an expanded vocabulary for the cause – readers who may also inspire us to show up for each other and get out there to make some “good trouble.”

Note: Disabled Voices Anthology will soon be available in ebook format

*

Margot Fedoruk has a BA from the University of Winnipeg and is completing a Creative Writing degree at Vancouver Island University. She is the recent recipient of VIU’s Meadowlarks Award for fiction and last year’s Barry Broadfoot award for Creative nonfiction/ Journalism. Her writing can be found in Portal 2019, Portal 2020, Island Parent Magazine, and The Globe and Mail. She is currently working on a memoir titled, Cooking Tips for Desperate Fishwives: An Island Memoir (with recipes) about her adventures raising her children on Gabriola Island with an urchin diver. Editor’s note: for The Ormsby Review, Margot Fedoruk has interviewed Shelagh Rogers and reviewed books by Kim Clark and Sari Cooper.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#872 Making some good trouble”

I was so so honored to be featured in this Anthology with such amazing writers and artists. This book and the review are wonderfully written. Thank you!