#864 Crossing Lake Tanganyika

Maison Rouge: Memories of a Childhood in War

by Liliane Leila Juma

Vancouver: Tradewind Books, 2020

$12.95 / 9781926890302

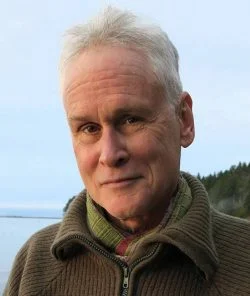

Reviewed by Howard Macdonald Stewart

*

Like many of us, I often find myself reading a couple of books at the same time. So, when I picked up Leila Juma’s thin tome I was also reading another book by a young Canadian woman. The other one was a more typical coming of age story, a hefty book written by a bright and accomplished young person enjoying high adventures while pondering future options and musing on the world she and her contemporaries have inherited. Leila Juma’s book, on the other hand, is a rather small volume that describes mostly terror and heartbreak. The comfortable lakeside home of her childhood, the Maison Rouge of the title, is destroyed as loved ones are murdered and the happy life she knew is obliterated by a scarcely comprehensible torrent of chaos and violence.

Like many of us, I often find myself reading a couple of books at the same time. So, when I picked up Leila Juma’s thin tome I was also reading another book by a young Canadian woman. The other one was a more typical coming of age story, a hefty book written by a bright and accomplished young person enjoying high adventures while pondering future options and musing on the world she and her contemporaries have inherited. Leila Juma’s book, on the other hand, is a rather small volume that describes mostly terror and heartbreak. The comfortable lakeside home of her childhood, the Maison Rouge of the title, is destroyed as loved ones are murdered and the happy life she knew is obliterated by a scarcely comprehensible torrent of chaos and violence.

I found the contrast between the two tales a timely reminder of the differences between our comfortable Canadian lives and those of many who live beyond our borders. While Leila Juma has now re-built her life as a Canadian, her story is a reminder that quite a few new Canadians have experienced trauma like hers. Maison Rouge: Memories of a Childhood in War offers us other Canadians an inkling of what some of our fellow citizens have been through.

Juma’s story is clear and short, maybe 20,000 words: no mean accomplishment given that the situation where she and her family found themselves in the 1990s was powerfully confused and complicated, a maelstrom of war that went on for years in the eastern regions of her native Congo. This Congo war followed directly on the heels of the mass murders of Tutsis and moderate Hutus that swept Rwanda in 1994.

The events in Rwanda shocked the world and became shorthand for genocidal violence. Much of our shock stemmed from the fact that the global community, led by the UN Security Council and the US in particular, had opted to stand back and let it happen. A tremendous amount of ink has been spilled in the years since including by our own Roméo Dallaire, who understood so little of Rwanda but was left permanently scarred by his role as head of a skeleton UN force there, which obliged him to stand by and watch as the slaughter unfolded (see Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands with the Devil, Penguin Random House, 2003).

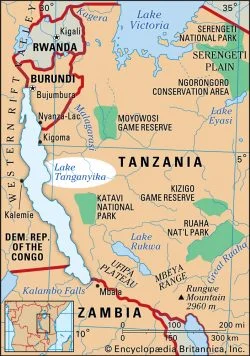

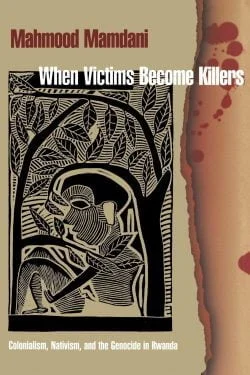

Unlike the nightmare in Rwanda, the Congolese war that engulfed Leila Juma’s family at Uvira on the western shore of Lake Tanganyika a little while later has received little attention. Yet this “other war” dragged on for years. The deadliest conflict in the world since the end of the Second World War, it killed some five to six million Congolese, mostly civilians and a great many of them children. This isn’t the place to discuss the complicated reasons why so little attention was paid to this war. As for its origins, see Mahmood Mamdani’s When Victims Become Killers (Princeton University Press, 2001), a remarkable summary of the complicated modern history of Africa’s crowded western Great Lakes region. Juma’s Maison Rouge is a great complement to Mamdani’s: a very personal story that offers readers a taste of what it felt like to live a bit of that history.

As in all wars, some people did very well by the one that enveloped Juma and her family. The eastern Congo, where it unfolded, was described to me by an old Belgian (who knew what he was talking about) as a “geologic scandal” – a land almost unbelievably rich in mineral resources of many kinds. This meant that once fighting broke out there, with much participation from neighbours like Rwanda and Uganda, many players had an incentive to keep it going as long as they could keep hauling out the loot. When I returned to the Rwandan capital, Kigali, in 2008, it looked far wealthier than it had twenty years earlier. And it wasn’t just the aid money pouring in. Rwanda had become a significant exporter of valuable minerals, like Coltan, that were being mined across the border in the Congo. Only in 2008, after fighting had dragged on in the Congo for many years, did the UN finally screw up the courage to publicly admonish Rwanda and suggest they ought to stop stoking the flames in their giant neighbour next door. Plus ça change.

Juma’s book ought to be required reading for Canadian secondary school students. They would find its brevity and clarity “user friendly,” but their teachers, to impart all the benefits it has to offer, would need to guide them though it. Young Canadians would need to understand that the terrifying collapse of young Leila’s world is not something that happened only in the time and place she describes. This is what war always does to civilians, all over the world. Leila’s childhood friend Amani, who is pressed into one army after another, suffers the tragedy of countless millions of young men swept up and changed forever by wars that turn them into killers – Juma calls them “tyrant soldiers” — and consume them like cordwood.

Juma’s old home on the shore of Lake Tanganyika, like Rwanda, the Balkans, Central America, and so many places rendered nightmarish by war, was a veritable paradise during peacetime. These are the quintessential “shithole” countries Donald Trump speaks of. Teachers could use this book to instruct students about the transition from paradise to the sort of place a moron like Trump feels compelled to dismiss as a “shithole,” and what it means for all of us.

Last but not least, Leila’s book can offer Canadian students a precious lesson in heroism. Our children and grandchildren need to know about people like Juma’s dad, who stood up for people in need before the soldiers took him away forever, or the fishboat captain who got them across the great lake to safety against the odds, or Juma herself and her mother and the millions like them who waste years in squalid refugee camps looking for ways to rebuild their lives while trying to cope with the trauma they drove them there.

Our kids also need to know why some Canadians call for our country to do more, not less, to help these victims and welcome more of them to our country. We need to ensure that young Canadians understand why it’s important to learn from heroes like the ones Juma describes, and to take a stand against the rising global tide of xenophobic hatred and fear being stoked by cynical demagogues like Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi, and Orban, and by those Canadians who align themselves with them. Juma’s book could make a valuable contribution to this kind of education.

*

Howard Macdonald Stewart is author of Views of the Salish Sea: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Change around the Strait of Georgia (Harbour Publishing, 2017). An historical geographer and semi-retired international consultant whose work has taken him to more than seventy countries since the 1970s, Howard has reviewed books for The Ormsby Review and BC Studies. His memoir of a youthful bicycle trip down the Danube with the war hero and debonair cyclist Cornelius Burke, “Bumbling down the Danube,” was published in The Ormsby Review (no. 21, Sept.-Oct. 2016), and his memoir, “The year of the bicycle: 1973,” followed in no. 788, April 2, 2020. He has also written a popular Remembrance Day piece, “Why the Red Poppies Matter,” in no. 420, November 11, 2018, as well as many book reviews, most recently of My Favourite Crime: Essays and Journalism from Around the World, by Deni Ellis Béchard, and Lands of Lost Borders: Out of Bounds on the Silk Road, by Kate Harris. He is now writing an insider’s view of his four decades on the road that followed his perambulations of 1973, notionally titled Around the World on Someone Else’s Dime: Confessions of an International Worker. He has lived on Denman Island, off and on, for more than thirty years.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#864 Crossing Lake Tanganyika”