#789 Protest, empathy, mourning

INTERVIEW: Tom Wayman with Nathaniel G. Moore

*

In a future issue of The Ormsby Review, Emma Rhodes will review Tom Wayman’s new book of poems, Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back: Poems for a Dark Time (Harbour: 2020), and as an appetizer we present an interview with Wayman by Nathaniel G. Moore – Ed.

*

Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back explores the question of how to live in a natural landscape that offers beauty while being consumed by industry, and in an economy that offers material benefits while denying dignity, meaning, and a voice to many in order to satisfy the outsized appetites of the few. A cri de coeur from a poet who has long celebrated the voices of working people, Wayman’s latest collection also grapples with why “anyone, in this era so profoundly lacking in grace, might want to make poems — or any kind of art.” But the keen sense of justice that drives the collection is tempered by the poet’s reluctance to take himself too seriously: “Centuries without the benefit / of my presence / have to be made up for / by my words.” The poet brings the perspective of age to our current troubled existence, with the reminder that as a society and as individuals we’ve faced perilous times before, and that our shared mortality links us more than circumstances and politics divide us. — Nathaniel G. Moore

Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back explores the question of how to live in a natural landscape that offers beauty while being consumed by industry, and in an economy that offers material benefits while denying dignity, meaning, and a voice to many in order to satisfy the outsized appetites of the few. A cri de coeur from a poet who has long celebrated the voices of working people, Wayman’s latest collection also grapples with why “anyone, in this era so profoundly lacking in grace, might want to make poems — or any kind of art.” But the keen sense of justice that drives the collection is tempered by the poet’s reluctance to take himself too seriously: “Centuries without the benefit / of my presence / have to be made up for / by my words.” The poet brings the perspective of age to our current troubled existence, with the reminder that as a society and as individuals we’ve faced perilous times before, and that our shared mortality links us more than circumstances and politics divide us. — Nathaniel G. Moore

*

Nathaniel Moore: The cover of your newest poetry collection, Watching a Man Break a Dog’s Back is striking, as is the title. How did this all come together?

Tom Wayman: The title of the book is an adaption of lines from a poem by the Santa Cruz, California poet Joseph Stroud, lines which I use as the epigraph to my poem “O Calgary” included in my collection. The publishing house was concerned that the title not be misinterpreted, so I suggested that for a cover image we find something that emphasizes that the poems in the book are against the surging lack of empathy in the world. I had in mind one of the contemporary Spanish artist Juan Genoves’ great paintings of demonstrations, but the rights holders of that art demanded more money than my book will ever make either for myself or the publisher. I found online instead photos that captured Genoves’ intent — militarized police clubbing demonstrators in France, England, Ukraine, Russia, the US, Spain, Greece and more. The photo that the in-house editor picked and added a striking background to is from a student protest in Chile.

I was struck by Joseph Stroud’s image for a couple of reasons. First, because in difficult times, those who are oppressed or in trouble can, and are often encouraged to, turn on others who are oppressed or in trouble. I wish it were needless to say that such activity benefits no one but the masters of this world, some of whom are only too eager to see us squabble among ourselves and hurt each other, rather than understand the true sources of our problems and take meaningful action to improve our lives.

Second, the stark and upsetting nature of the title phrase seemed to me to offer an opportunity reflect on the theme of the collection’s poems: the issues the majority of Canadians struggle with currently in attempting to build a decent life. I know people love their dogs, but to me a starker and more horrible image than that evoked by my title is that in the stationery store in the small town in southeastern B.C. near where I live — set amid mountains and valleys covered in forests — you can only buy paper made in the USA, China, or South Korea.

Nathaniel Moore: What role does humour play in your writing?

Tom Wayman: Humour is important to my writing, because humour is the way we get through the day: a great many person-to-person interactions during the course of the day include a funny comment or a joke. If literature is intended to tell the human story, as it’s constantly lauded (and funded) as doing, humour has to be as central to literature as it is to life.

In addition, humour provides perspective to a difficult — threatening, humiliating, socially awkward, etc. — situation more effectively than any other verbal or written means. Authority hates humour because humour by its very nature undermines authority’s stance — humour brings authority, pomposity, solemnity down to earth, which is where all humans, whatever their so-called “status,” dwell. Critics, therefore, most often view humour as “not serious,” i.e., second rate. Yet humour’s accomplishment — the creation of perspective — is as vital to society as any other contribution literature is alleged (and funded) to make to society.

I don’t think humour’s role has changed over the decades. J.B. MacKinnon, in a presentation about his book on rewilding, The Once and Future World (2013), shows an amazing photo taken on the Seattle waterfront of an eagle snatching up a salmon from the ocean. In the foreground, a young guy sits on the tailgate of a pickup, bent over his cellphone. MacKinnon speculates that he’s texting: I’m @ the waterfront. May b I’ll c an eagle!

Nathaniel Moore: A few elegies appear in your new collection. Is the creation of these poems and the dedication to these individuals part of letting go / immortalizing things for you?

Tom Wayman: The poems that respond to people who have died are not intended to be solely an appreciation of these people, or a mourning of their deaths, but rather arise out of my interest in the arc of people’s lives. For the same reason, I frequently read obituaries. I’m constantly amazed at the lives people fashion for themselves, and hence for the people around them. Frequently I admire the contribution those who have died have made to family and community, or the arts, or all three. And as I mention in the prose introduction to the section of my book that gathers elegies, there is something of the “self-elegy” in what I’ve written: thinking about the lives of the dead gives me insight into the arc of my own life.

Nathaniel Moore: Release and Last Testament seem to be a sequence of sorts about endings and beginnings. Are you positioning these poems as contrasting signifiers of life and death?

Tom Wayman: These poems are both self-elegies pure and simple — celebrating my pending disappearance from the planet, and the planet’s memory. In one case the poet turns into pollen, and in the other he is reduced to the single tone of a bell reverberating through the cosmos.

Nathaniel Moore: In ‘Literally’ you write, “Why does light never age?” Later in the same poem you describe profiteering food commerce being so far removed from the toil on the field. Do you see the capitalistic system as the ultimate disruptor of nature?

Tom Wayman: This poem arose because I was struck by two quotes attacking literalism by two different U.S. poets whom I very much admire — the magisterial Robert Bly and the Washington state rancher-poet Joseph Powell. My poems, of course, are nothing but literal! Bly was raised in Minnesota farming country, and both poets are astute observers of the natural world. Hence much of my poem — intended as a defence of literalism in the arts — concentrates on natural imagery. But because of my long fascination in why the world of daily work is a taboo subject in the arts, my poem moves to how we currently organize food production, distribution, and profit-taking.

The poem doesn’t name corporate capitalism as the villain here — virtually every organized economy from time immemorial has not treated the natural world very well. Often the ecological impact of a small population is confused with ecological wisdom, but there’s lots of anthropological evidence to the contrary. Ronald Wright’s Massey lectures, A Short History of Progress (2004), is one place this is detailed. That said, I do have lots of poems in the current collection that attack corporate capitalism.

Nathaniel Moore: Can you describe a good writing day? What is your routine?

Tom Wayman: I live on an acreage about 60 km. west of Nelson in the Selkirk Mountains of southeastern B.C. A good writing day for me begins with breakfast, followed by a half hour or so of exercise (at my age, a must), and sitting down at the computer some time before 10 a.m. After a brief scan of online news items, and then a printing out of pressing emails to be dealt with later, I begin to write. First drafts of poems are longhand, but otherwise I compose directly on the computer. I work away steadily to 2:30 or 3 p.m. — I take a break to make lunch, but eat it at the computer.

The balance of the day is spent outside, tending to the seasonal chores of the estate. I work longest hours in the spring getting my far-too-extensive gardens in (flowers and vegetables), but there’s always more to do outside. When I come in from the grounds, I generally return to the computer for either more literary work or to answer emails, letters, etc. I’m a member of various local literary event committees, principally Nelson’s annual Elephant Mountain Literary Festival, all of which involve organizational chores for me to complete. And for some reason I’m often the designated budget officer for these committees, so developing and updating budgets can also preoccupy me once my literary writing, and my time outside in the weather, is done for the day.

My fear is that if I ate supper immediately on returning from the garden, I’d be too tired afterwards to return to my desk and tackle all these non-literary chores. So instead I often work late, and end up eating supper around 10 p.m., just before bed.

*

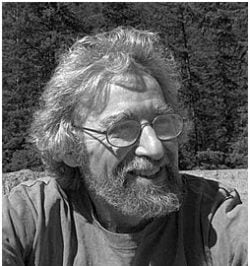

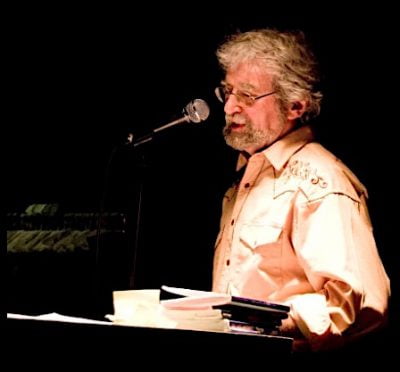

Tom Wayman was born in Ontario in 1945, but has spent most of his life in British Columbia. He has worked at a number of jobs, both blue and white-collar, across Canada and the U.S., and has helped bring into being a new movement of poetry in these countries — the incorporation of the actual conditions and effects of daily work. His poetry has been awarded the Canadian Authors’ Association medal for poetry, the A.J.M. Smith Prize, first prize in the USA Bicentennial Poetry Awards competition, and the Acorn-Plantos Award; in 2003 he was shortlisted for the Governor-General’s Literary Award. He has published more than a dozen collections of poems, six poetry anthologies, three collections of essays and three books of prose fiction. He has taught widely at the post-secondary level in Canada and the U.S., most recently (2002-2010) at the University of Calgary. Since 1989 he has been the Squire of “Appledore,” his estate in the Selkirk Mountains of southeastern BC.

*

Nathaniel G. Moore is the author of seven books including Savage 1986-2011 (Anvil Press), winner of the 2014 Relit Award for Best Novel. His book reviews have appeared in the Georgia Straight, the Globe and Mail, and Canadian Literature, and he reviewed Scarred, by Sarah Edmondson, for The Ormsby Review (no. 706, December 21, 2019). Formerly of Pender Harbour, Nathaniel now lives and works in in Fredericton, New Brunswick.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “#789 Protest, empathy, mourning”

I’m happy to hear about Tom Wayman and his forthcoming book of poetry. Empathy and elegies are on my mind these days. Thank you.