#557 Sea otter slaughter and survival

Sea Otters: A History

by Richard Ravalli

Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press

$45.00 (U.S.) / 9780803284401

Reviewed by Robin Inglis

*

This slim volume — about 140 pages of narrative excluding an appendix of data tables involving the California fur trade, endnotes and a full bibliography — provides readers with a fascinating overview of the life, times and history of the smallest marine mammal in the North Pacific Ocean. It is at once natural history, commercial history, imperial and nation defining history, species extinction history, conservation history and tourism/entertainment history.

This slim volume — about 140 pages of narrative excluding an appendix of data tables involving the California fur trade, endnotes and a full bibliography — provides readers with a fascinating overview of the life, times and history of the smallest marine mammal in the North Pacific Ocean. It is at once natural history, commercial history, imperial and nation defining history, species extinction history, conservation history and tourism/entertainment history.

With the scientific name Enhydra lutris, sea otters have traditionally lived for millennia in the coastal waters of a giant arc from Baja California in the southeast, north through the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, round the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, to Kamchatka, the Kuril Islands and on to Japan in the southwest. About four feet long and weighing an average fifty to sixty pounds, sea otters are ecologically important for protecting kelp forests from the predations of sea urchins (they use kelp to avoid being swept out to sea) and in this way they support fish and other marine species who need the forests to survive.

In human history, however, the otters have been prized, and therefore hunted, for their fur. Unlike whales, for example, sea otters rely on the densest fur of any species in the world to protect them from the cold water they live in. Their coats contain up to a million hairs per square inch, with an undercoat of longer guard hairs. As heat loss is a major issue, the otters spend up to ten percent of each day grooming their fur to prevent contamination. The overall result is a wonderfully rich and luscious fur. Predators in the wild include whales, sharks and eagles (who take their pups) but their inshore existence has historically made humans their prime threat. Evidence of hunting dates from 10,000 BC in Japan and from about 8,000 BC in Haida Gwaii.

By placing the animal at the centre of this study, Ravalli creates a bridge — a continuum if you like — between a variety of research fields that authors have written about separately, be they the fur trade, aspects of which, Alaskan, Northwest Coast and Californian, have been extensively documented, or efforts at conservation as sea otters were hunted to the very edge of extinction by the early 20th century. He also identifies for us in British Columbia that it was furs from Hokkaido and the Kuril Islands that first reached China as a luxury commodity in the 15th century, not those from the Aleutian Islands or Vancouver Island in the 18th century.

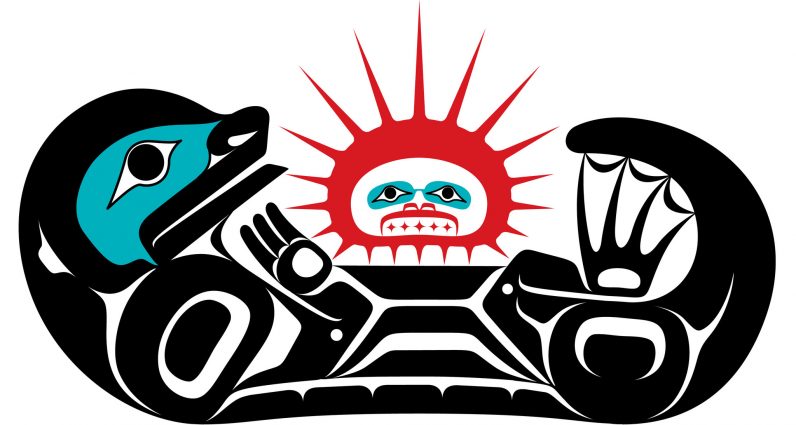

It is hardly surprising to read that sea otter furs were used and traded by Indigenous communities around the North Pacific long before non-native societies developed an interest in them as a commercial commodity. The oral traditions and mythologies of the Ainu of Japan as much as of the Haida in Canada reflect their strong connection with the sea otter upon whom supernatural qualities were bestowed. There is evidence of a clear spiritual importance of the animal to many Pacific communities, and sea otter fur was not just prized for clothing in general but for special decoration and as a trade item that could be monopolized and therefore served to enhance the power of local chiefs.

The book is set up with a short Introduction to the world of the sea otter since before recorded time. Then the “history” is covered in five chapters, whose titles give an idea of the subject matter presented: “Rakkoshima, the Sea Otter Islands;” “Promyshlenniki and Padres;” “Boston Men;” “Near Extinction and Reemergence;” and “Nukes, Aquaria and Cuteness.”

Historians of the Northwest Coast maritime fur trade have tended to use the benchmarks of Vitus Bering’s Second Kamchatka Expedition (1741-42) and James Cook’s sojourn on Vancouver Island (1778) as the beginning of the “fur rush” in the North Pacific. These voyages unleashed extensive hunting across the Aleutians in Alaska and on the Northwest Coast respectively. However, in his first historical narrative chapter, Ravalli details the existence of a flourishing fur trade on the Asian coast, centred on the Kuril Islands — the Sea Otter Islands — where Urup Island played a similar role to that of Vancouver Island and later Haida Gwaii in North America. The Ainu became key figures in the trade with Japan. As the Russians reached the Pacific and established a border with China in the late 17th century, they pushed south from Kamchatka. Furs garnered were sold into China through the famous border market town of Kiakhta. A situation that was to later play itself out in America developed — the Ainu as middlemen, beneficiaries yet victims — were caught between imperial powers vying for hegemony.

It is interesting to read that Grigorii Shelikhov established a settlement on Urup in 1795, similar to the one on Kodiak a decade earlier, and that Russian American Company manager, Alexandr Baranov, had authority over the Kurils. The islands were vigorously defended by both Ainu and Japan, and Russian activity was blunted though never eliminated by any means. The islands became a frontier of tension for the entire 19th century. Ironically, sea otters, although hunted extensively in the region, were saved from the disastrous effects of the unrelenting Aleutian and Northwest Coast hunts, as the Russians found enslaving the skilled Aleuts and an unobstructed advance to America easier to undertake.

If the sea otter became a defining feature of relations between Japan, Russia and China, the animal was also central to imperial maneuvering in the eastern Pacific, where events in the late 18th century paralleled the Kuril Islands. Again, a Russian advance — this time post Bering towards America — alarmed authorities in New Spain as it had Japan in Asia. Spain had long assumed hegemony over the Northwest Coast, but six voyages from Mexico, 1774-1791, five of them into Alaskan waters, did nothing to arrest Russian progress; and the Russian American Company was able to consolidate itself in New Archangel (Sitka) by 1804, send Aleut hunters into San Francisco Bay, and build an outpost, Fort Ross in California, in 1812.

By that time Spanish and Russian activity in California had largely decimated the sea otter population. However, with her New World resources stretched within New Spain and supplying the missions in Baja and Alta California, combined official inertia and opposition from the Philippine Company that had a monopoly of trade with China, meant that Spain was never able to use her geographical advantage to engage effectively with the fur trade as a way of establishing (and paying for) her presence north along the Pacific coast of North America. Elsewhere, the Canadian historian-geographer James Gibson has documented no less that nine proposed plans to do just this; all failed.

As authorities in Mexico City fretted about a Russian threat to New Spain in the 1770s, James Cook arrived on the coast to search for the Pacific portal to the Northwest Passage. Before running the coast north from Oregon to Alaska he stopped on Vancouver Island. Within two years, the furs so casually traded for in Nootka Sound, fetched exorbitant prices in Canton. In the early 1780s, as this news became known and Cook’s journal was published in 1784, trading voyages from Asia, England, and Europe descended upon the coast. In addition, ships from New England — carrying “Boston Men” — arrived, bringing persistence and entrepreneurial skill for the best part of three decades that, coinciding with British distraction with the Napoleonic Wars, led to their domination of the trade from California to British Columbia. As Russian-sponsored hunting in the north melded with British and American trading with Indigenous communities in southern Alaska and British Columbia, the wholesale slaughter of local sea otter populations drove the animals towards the edge of extinction by the turn of the 19th century.

Spanish, Russian, and American activity in California in the first two decades of the new century also did the same. Ravalli describes the central role of native participation in hunting the otters and trading their skins, the different voyages arriving from afar and setting sail to cash-in in China, and the “contributions” of a panoply of actors such as Esteban José Martínez, John Meares, Robert Gray, and William Sturgis, that marked the ebb and flow and the rise and fall of the regional maritime fur trades — north, central and south. He also places the Nootka Controversy, Astoria, the effects of the arrival on the coast of the overland fur trade, and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia Department into the context of the world of sea otters and their destiny. In doing so, he presents not only a story of violence and greed, a voracious appetite for commercial profit, but also one in which the hunt and trade in pelts along the Pacific shores of coastal North America generated imperial rivalries that determined national boundaries.

After the maniacal years of the American maritime fur trade had finally played themselves out by the second decade of the 19th century, sea otter populations continued to decline to the point of extinction in certain localities despite a recognition, from that time, that some regulation was necessary in the interests of conservation in aid of future hunting opportunities. Ravalli devotes a chapter to this. Enforcing conservation measures ran the gamut from unsuccessful to marginally beneficial. For example, Russian American Company efforts at severely limiting the hunt saw some success in Aleutian areas that had essentially been stripped of animals; however in California, Mexican officials proved unable to control Russians and Americans from bringing the animal population there to record low levels. The root cause of the problem was that female otters usually give birth to only one pup at a time; and even if females were spared in the hunt, which was much more likely to be indiscriminate anyway, population recovery was always going to be a slow process.

When American hunters and traders continued to seek profit over any concerns for the ecological impact of their activities following the division of Oregon in 1846, the absorption of California into the United States in 1848 and the purchase of Alaska in 1867, those sea otter populations that remained only barely viable came under continuing pressure. With native communities north of California also taking otters, they had seemingly become extinct in Washington, Oregon, British Columbia, and southeast Alaska by the early years of the 20th century. Later 19th century investigators had feared an almost total extinction across the entire historical range of the animal. Conservation efforts at the time became more connected to seal hunting than otter protection, and the author maintains that the pelagic emphasis of the Anglo/Canadian, American, Russian and Japanese North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911 did nothing to help the inshore world of the sea otter, but it did serve to focus attention on the general plight of species at risk. In 1913, an Aleutian Island Refuge was created and California banned the killing of otters. Even if any animals actually continued to exist in British Columbia, however, sea otter hunting was not officially prohibited until 1931.

But the early-century trend has continued over the last hundred years as nations including Canada and the United States have developed strategies to protect sea mammals in general and to regulate hunting. Together with relocation — the current BC sea otter population (over 5,000 in 2008 and so more today) — is made up of descendants of the 89 Alaskan otters that were relocated to Vancouver Island in the years 1969-72 — these strategies have reversed the historical calamity that befell American sea otters for the over hundred and fifty years since the mid-18th century.

In his final chapter Ravalli explores the question of how we think about sea otters today. He cites a series of “events” that together have helped shaped our response: the romanticizing of the sea otter in natural history television films and in literature — articles in journals and newspapers and natural history books — especially aimed at children, as “cute,” “playful,” and “gregarious,” as indeed they are (and were first recorded as such by Georg Wilhelm Steller, Vitus Bering’s naturalist); the furore around the three underground nuclear tests on Amchitka Island in the Aleutians (1965, 1969 and 1971), the last of which killed at least a few hundred and maybe as many as a thousand in a place where the largest population of extant sea otters in the Pacific lived at that time; the Prince William Sound, Exxon Valdez disaster of 1989 which killed over three thousand otters, highlighted their plight and catapulted them to iconic status as hapless victims and a symbol for environmental conservation; and finally their appearance to “entertain” millions of visitors at aquaria since they first arrived in Seattle in 1954.

Nyac was a favourite at the Vancouver Aquarium having arrived there from Alaska as one of the few survivors of the Exxon Valdez oil spill. The charisma of the sea otter today has in fact created an image that has allowed it to come to ever-wider public attention, even if has commodified it in a way diametrically opposite to its role in history and especially in the 18th and 19th centuries. But there are problems with “cuteness” that often obscure the fact that these are wild animals prone to serious aggression and, in larger numbers, can negatively impact local commercial fishing. The author ends by calling for a more nuanced view of sea otters both in the nature and in their potential social and political impacts on coastal communities.

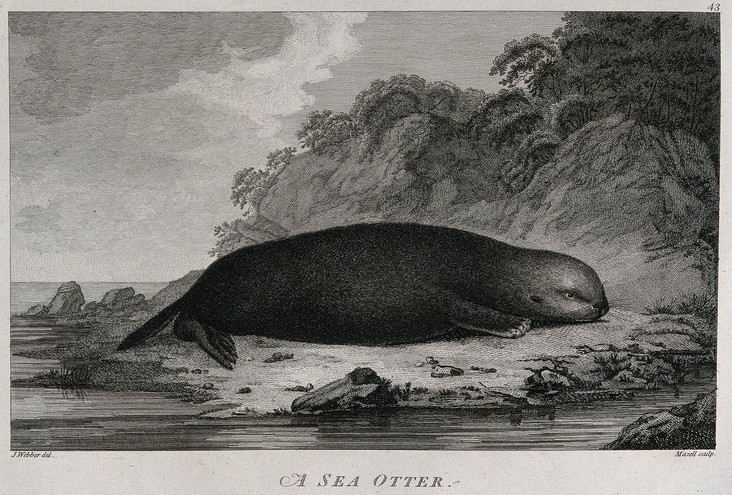

Ravalli has written a book that is at once informative and often fascinating. The narrative is tight and sometimes one would appreciate a bit more expansion; for example, when James Cook’s journal was published, it was Lieutenant James King who was responsible for the third volume after Cook’s death. In it he not only discussed the substantial benefits of developing a fur trade between America and Asia but also presented a blueprint as to how it might be prosecuted. Thirteen helpful illustrations are provided, and this reviewer’s only serious quibble is that a few maps would have been useful. One cannot always expect readers to know their geography.

Postscript to this review. Prior to the modern fur trade there were probably at least 150,000 sea otters between Baja California and Japan, and maybe even twice that number. Today the Vancouver Aquarium website lists the following numbers: Russia, approximately 22,500; Alaska, approximately 71,500; British Columbia, approximately 6,000; Washington State, approximately 550; and California, approximately 2,500.

*

Robin Inglis is a former Director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum and the North Vancouver Museum and Archives. He is a Fellow of the Canadian Museums Association. After graduating from Cambridge University with a degree in history, he came to Canada to teach before taking a Master’s degree in Museum Studies at the University of Toronto. Since the 1980s he has studied, written and lectured on the early exploration of the Pacific coast of America, completing the Historical Dictionary of Discovery and Exploration of the Northwest Coast of America (Scarecrow Press) in 2008. He has curated major exhibitions on Pacific explorers Jean François Galaup de La Pérouse (1986), Alejandro Malaspina (1991), and James Cook (2015). Currently he is working with a colleague at UVic on a new translation and annotation of the 1789 Nootka journal of Esteban José Martínez; it will serve as a companion to the work he and other colleagues undertook to publish the 1792 journal of Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra in 2012. Robin has received decorations in recognition of his work as a museum professional and historian from the governments of France, Spain, and Canada. He lives in Surrey, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher: The Ormsby Literary Society

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster