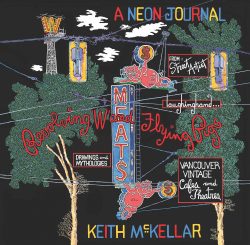

#449 Keith McKellar’s Vancouver

Revolving W and Flying Pigs: A Neon Journal of Vancouver Vintage Cafes and Theatres

by Keith McKellar/ Laughing Hand

Victoria: BoneYard Ink Books, 2018

$50 / 9781775357704

Orders: direct from author at www.laughinghand.com

Reviewed by Grahame Ware

First published Dec. 16, 2018

*

This publication is an exciting and colourful recasting of Keith McKellar out-of-print, Neon Eulogy (Victoria: Ekstasis Editions, 2001). Revolving W and Flying Pigs is a must-have companion to his first book for those of us who revelled in the time when neon and psychedelia danced viscerally and mindfully in the jewelled, rainy streets of 60s, 70s, and 80s Vancouver. Through his brush and words, a huge chunk of social history is channeled laterally by Keith McKellar, a.k.a. Street Artist and Laughing Hand, a Homeric bard-with-an-ink-brush and a complex and technical colourizing process. His artwork is based on the skeleton of pencil done in situ, which is then built up in the studio by the southpaw sketcher with freehand ink and many more technical stages before arriving at his finished work.

This publication is an exciting and colourful recasting of Keith McKellar out-of-print, Neon Eulogy (Victoria: Ekstasis Editions, 2001). Revolving W and Flying Pigs is a must-have companion to his first book for those of us who revelled in the time when neon and psychedelia danced viscerally and mindfully in the jewelled, rainy streets of 60s, 70s, and 80s Vancouver. Through his brush and words, a huge chunk of social history is channeled laterally by Keith McKellar, a.k.a. Street Artist and Laughing Hand, a Homeric bard-with-an-ink-brush and a complex and technical colourizing process. His artwork is based on the skeleton of pencil done in situ, which is then built up in the studio by the southpaw sketcher with freehand ink and many more technical stages before arriving at his finished work.

The format for this publication has been bumped up considerably from Neon Eulogy with much more image space and high quality paper. Revolving W and Flying Pigs benefits from a lovely, large, square 11 1/2” format. Replete with colour in all its neon glory — glowing in the dark, furry night – every entry has pictures and text tucked into a capacious page. This excellent production fuses McKellar’s art and lyricism. Wonderful stories and narrative histories buttress it marvellously and make it far from some rare art book.

The genesis of McKellar’s latest book is truly a case of unfinished business. In Neon Eulogy, the dedication was a poem simply titled “W,” a homage to Woodward’s Department Store’s distinctive revolving red sign. In a sense, then, the W is his Muse:

‘W’

unlit/stilled — foreboding/ melancholy

unturning

as a stage clown

used to his dance

flood-lights

black night

bright faced

and blinking

Now a sad face

a naked droop in a dull sky

tattered and peeling

raw and bleeding

brave ‘W’

bleeds in the rain

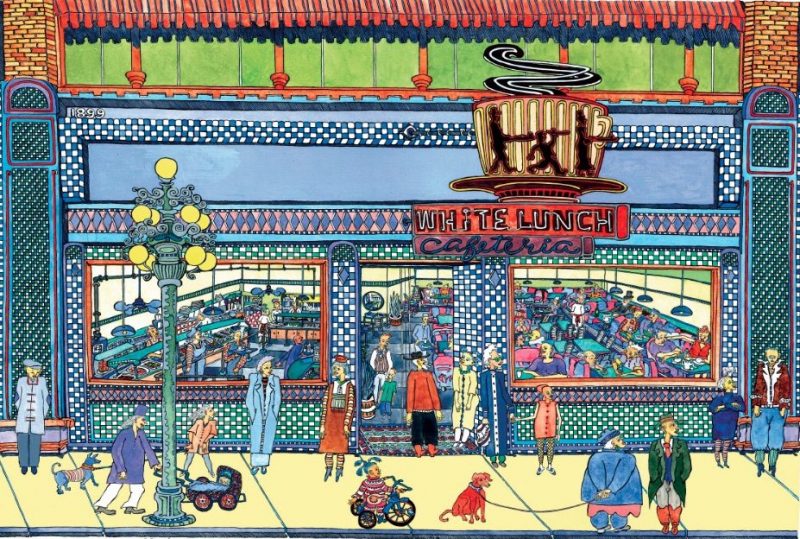

McKellar, seventeen years later, has kept his word to the W. But he hasn’t merely reconfigured that first book. He’s built upon its foundations to give us new entries for places such as the 2400 Motel Court, Helen’s Neon Girl, Cates Towing, White Lunch Cafeteria, Save-On Meats, plus a new Foreword and Afterword. McKellar is in charge of the entire production as artist, writer, editor, and publisher. For those unfamiliar with Neon Eulogy, sadly the only colour was on the cover. But sad no more be!

Once you dive into Revolving W and Flying Pigs, you will inhale it — possibly after doing the same with a little homegrown whilst adding to the reading ambience with some Don Thompson, Cannonball Adderley, or Powder Blues Band with Tom Lavin playing in the background.

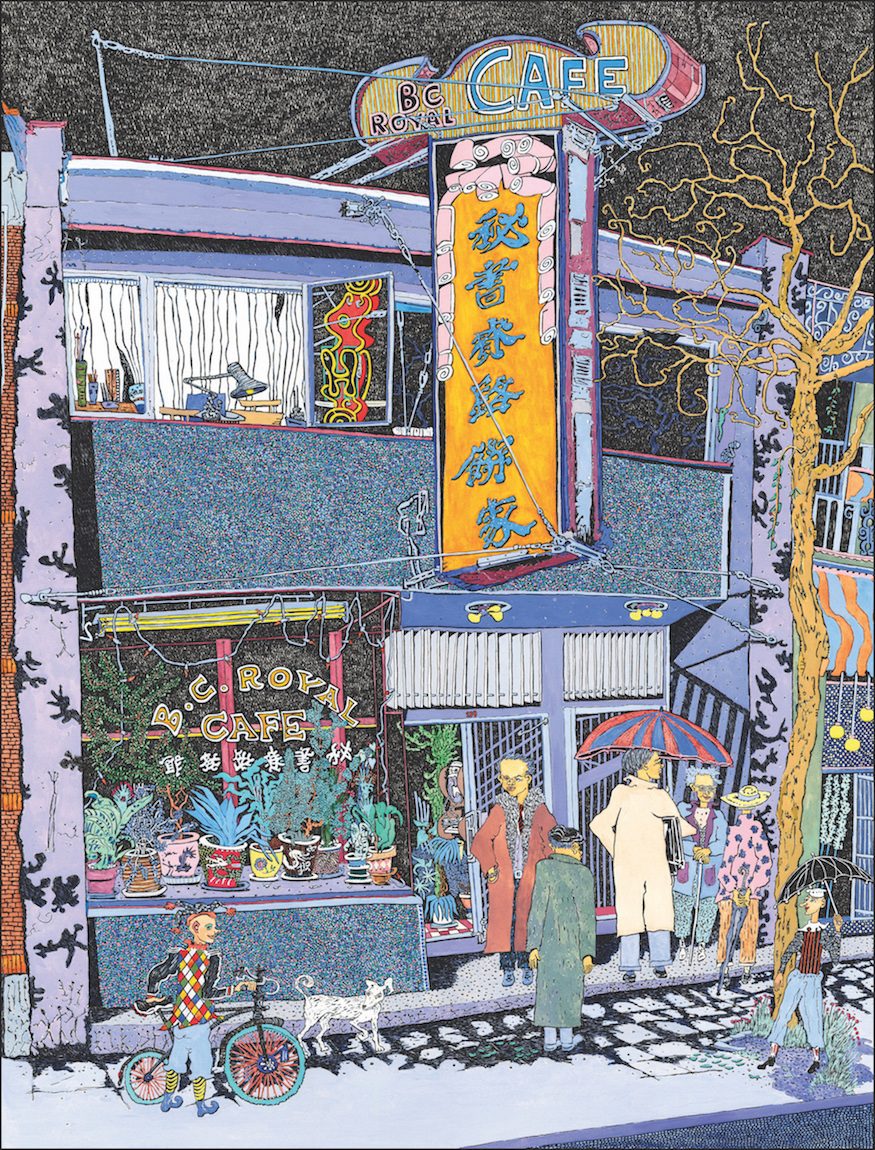

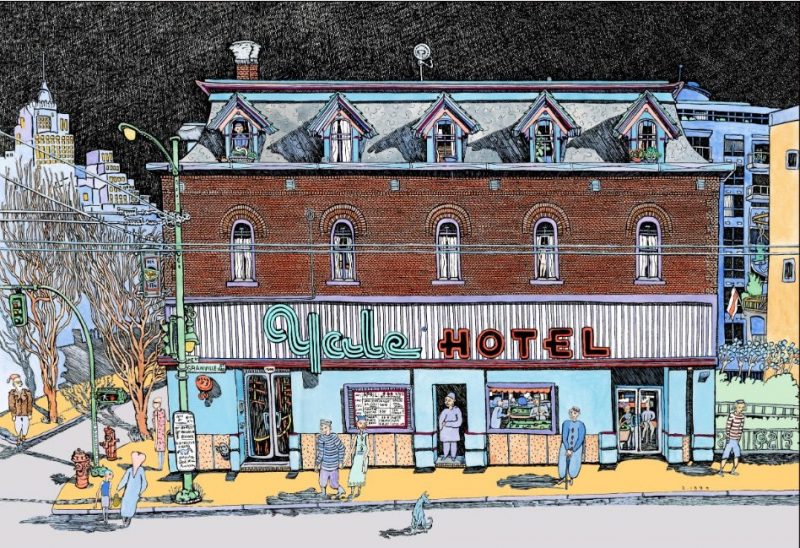

In this publication we have a street-side, street-wise perspective of hotels, cafes, and restaurants of a vintage that was once commonplace and even ubiquitous in Vancouver, especially in Chinatown.

McKellar’s places are, generally speaking, the early 20th century buildings whose sensibilities and personalities acquired a charm in their slow decay and demise. And if the memory has faded and gone cold, McKellar’s book is like a Bristol Cream sherry that warms the cockles of memory and of your history heart. The evocative pictorial quality of the book brings the past back in a rush. These paintings are for history lovers who, jaded with monotonous discourse, like their stories jazzed up with poetic panache. McKellar’s narratives, like those in John Belshaw and Diane Purvey’s Vancouver Noir (Anvil Press 2011) hit all the right notes in spades. But unlike that fine book, this one is not written by teachers of history.

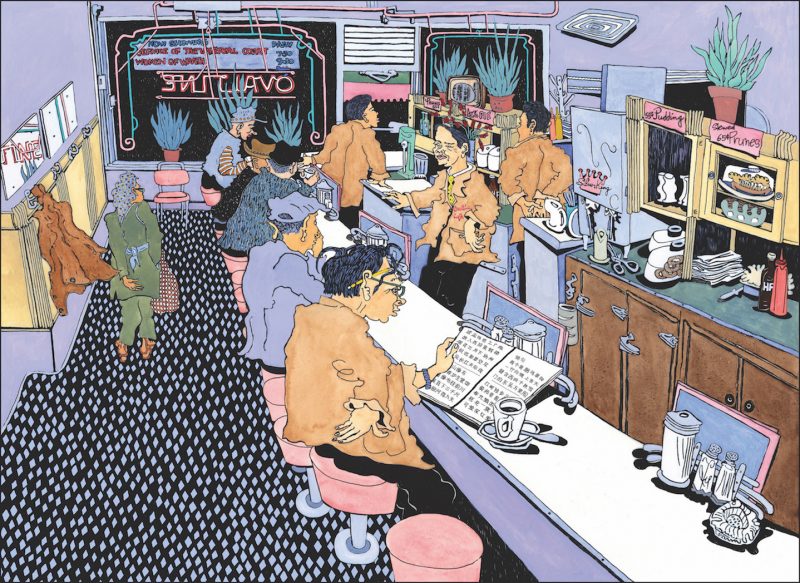

The Ovaltine Cafe Interior (p. 12) represents another change from the first book. Gone is the boney southpaw hand of the artist in the lower right hand corner. The menu of the nearest customer is now not merely a menu. Rather, it is script from a late Tang dynasty scroll. The more you linger over the minutiae of McKellar’s paintings, the more you see.

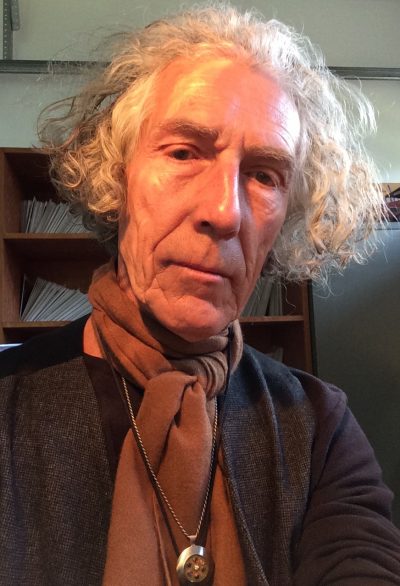

Pathos and nostalgia fill the pages with McKellar’s stream of consciousness narrative, reminiscent of the performance-partial Beat poets like Corso and Ginsberg. Curiously, the wiry McKellar bears such a striking resemblance to William S. Burroughs that you could be faulted in thinking that they’re related. And, in a sense, they are.

But the thing is this: McKellar’s writing is clearer and less smacked-up, no APO-33 to imprint the mind as with Burroughs’ entangled peregrinations and thoughts. This book demonstrates McKellar’s independence from any artistic scenes or literary cliques. Despite this, or maybe because of this, he shines. Thankfully, the narratives have a raw and unedited feeling, unlike some literary works that are as polished as agates left tumbling overnight by an absent-minded lapidary.

The fibrous quality of his writing is its strength, not unlike the village-style chop suey, cooked with fire and air, that sustained McKellar while he worked as a public chauffeur. This phase of his life was the quart-of-milk-between-his-legs period. As an alcoholic and tobacco addict, driving cab was a recovery program as much as anything. He did that for nine years before he transformed into an artist.

Of McKellar’s Muse, the once revolving red W sign of Woodward’s, he says this:

Breaking all the rules of the reactionary 60s, the ‘W’ gets up there and does his sensational twirling act before regulations are laid down. “No rooftop signs, no turning allowed. No flashing.” ‘W’ does it all. Red neon runs up the tower sides like showtime legs at night. A symbol of freedom for a standard of life. A pivotal ecological footprint. A handwritten epigraph to the city. Cusp. A true Vancouver wonder …. Perhaps a sad clown … but one with dignity. Replaced by a silly plastic clone (p. 42).

This wouldn’t be the last time corporate Vancouver flexed its Philistine muscles. “Send in the clones!”

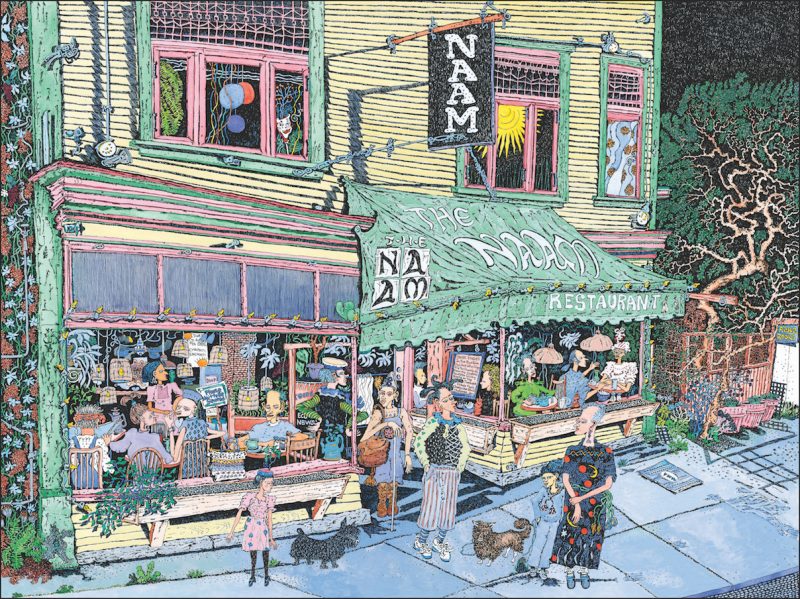

McKellar’s entry for The Naam Restaurant is condensed from that in Neon Eulogy but still has some striking imagery: “This last true 60s cultural phenomenon has journeyed (caravan-like) through time to be in our midst, as though some organic hologram. One big, whittled wood carving from an ancient, zen forest of gnarly trees” (p. 60).

Revolving W and Flying Pigs is an extended elegy and ode to the neon Vancouver of old. McKellar writes with as much authenticity about Vancouver as any poet, as when Peter Trower seeks heat from the Christmas display windows of Eaton’s. This is neon as a semiotic configured, a flashy often kinetic totem that staked out terroir for young Boomers and night-lifers in general. These were the beacons that attracted the culturally and physically hungry nightfall clan. They beamed and flashed, lifted peoples’ spirits, sparked joy across the classes. These signs with neon coursing in their glass arteries declaimed the portal that was both a refuge and a cultural consort.

McKellar’s work is a belated but much-needed tribute to the sky and the dead and departed spirits, emceed in dark and empty alleys in front of derelict buildings, where now the only light and colour is sparked and drawn from the crucible of memory and where the actions of hand and tongue just wait for the latent spark of retrospection.

“Here’s to all that was great way back when!” proclaims Laughing Hand. No shame. No crying. Just a finely-crafted melancholic reminder of what it was really like for him and for the earlier Keith McKellar. The process of his imaginative neon eulogy project transformed McKellar into Laughing Hand, a handle given to him not by any member of his tribe but seemingly from the neon and Vancouver’s dark sky. His is the hand that joyfully remembers and colourfully connects the past with the present. The W bleeds into his persona. This is the moment when he was born as a street artist, laughing at his hand and his ability to do this. This was the authentic personality he’d been striving for as he drove his taxi back and forth across town in his self-directed work cleanse.

I asked Keith what were the sources of his inspirations. An autodidact? “Yes.” Mork from Ork? “No! I credit the 11th century Latin scholar, Hilarius, as my main inspiration.” Curiously, this is the realm of the jongleur (wandering minstrel), a name that was later ascribed to the Goliards. They were known for their satirical poetry written in Latin, the common language that underpinned their education. They were the first to question the concepts of the church in Medieval Christian times. Think Piers Plowman. The late Joachim Foikis, Vancouver’s first and only official Town Fool, would have had something in common with this satirical tradition.

As for McKellar, inspired and transmogrified into Laughing Hand, he would now dress up in some funky clothes and sketch the places he loved and talk to the people who owned and managed them. On the back cover of his book is this blurb of self-description: “Appearing and disappearing in the street as though a Hopi clown off the rooftops, with his show wagon, surviving in the moment of his making the drawings and selling his prints from a string and an umbrella.”

McKellar told me over the phone that Rachel Berman (a.k.a. Susan King), the late illustrator from Victoria, helped get his drafting skills off the ground. She also provided inspiration and insight into own her novel and off-beat illustrations. There is definitely something of her influence in his work.

The dazzling pictorial quality of Revolving W & Flying Pigs wouldn’t be anywhere near the same without McKellar’s verbal imagery, hammered and smithied over his years of driving for Black Top Cabs. His narrative is mercifully devoid of the devices that doomed poetry and stripped it of its wide 60s and 70s audience, imposing a freeze-dried minimalism that was underwhelming in its descriptive range. McKellar’s voice, though, often overstates its laments, a witness bemoaning the end of an era. This may be because there is so much to mourn. With each brush stroke and painting, he wistfully remembers our town with a high-def, fully-dilated eye and with his writing underpinning it. Take for example the entry for the Lucky Times Café:

A cafe takes on the character of the people that visit it. Upstairs the old rooming house called the Cambie Rooms is still standing intact; nearly sculpture, wearing a hundred coats of paint … the crinkle of elderhood, detailed bay windows, intricate stacked corners and ledges. I see an apparition of an occupant in his regular spot at his window after he’s passed away. Through the nightmare tangle of droopy, alley electrical wires, the surreal “W” pokes up phantom and periscope in an ironic twist on the mouth of the sky. Caught orbital dreamer…. We must squint to get a glimmer of its authentic face to see through the disappearing and the disappeared (p. 45).

This is potent imagery, beautifully delivered. McKellar’s is the full-throated voice of the cantor singing the final rites in ways that are neither overtly maudlin nor sentimental in a clunky way because it is all so true and real. He expresses our group sadness. I identify with this book and the times it portrays because I was there. There’s also something quaintly subversive in his art. You can faintly hear the voice of Gil Scott-Heron from 1970, echoed in the pictures’ subtext, that “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.”

In this gallery book, as in its predecessor, McKellar chants softly, laying down riffs and images like saxophonist Gavin Walker at The Classical Joint. “The Joint” was always a popular spot, often packed and hard to get into. This could cause frustrations. Folkie musician Joe Mock once struck up a spontaneous little ditty when a hassle seemed to be erupting at the door: “Move over (call back)… Move over (call back). Do it riggidy jig … We’ve always got room for Marty … ‘Cos Marty is not very big.” Needless to say, after that, fifty sets of eyeballs cooled out this cat.

McKellar’s style fuses sensibilities from an era when there really was a classical joint shared by all, achieved “with a little help from your friends.” His art is a freeze-frame in time; a time when folk and jazz mingled without any stilted self-consciousness, like at the Joint. Paul Horn became Jeremy Steig and then, voilà … Holly Burke! Joni Mitchell, Queen of Folk, appeared in the audience after toddling on down from her home in Sechelt; then jetting down to her Laurel Canyon recording studio where, for another ten years, she threw herself on the jazz pyre. There was nowhere else to go after Blue.

But it wasn’t just music. Integrative art forms and styles were blasting through the neat little walls of convention along with artists of every sort — fearless, sensing, trusting, searching for the deeper and more authentic truth. It wasn’t always pretty. Many promising people crashed and burned. Riding the uncharted waters and ragged waves of the zeitgeist they were choiceless about the outcome.

The nostalgic core of McKellar’s book are the images, flash-frozen in the pulsing arc of the times. The book’s sadness and sense of loss makes us appreciate what we had and makes us feel it all over again. McKellar’s era gave rise to a critical mass for our culture as we now know it. It got the ball rolling. The problem now, of course, is that we’ve gone from too little, to too much, too soon. Capitalism has reared its ugly, freaked-out head of overproduction — at a cost.

With Revolving W and Flying Pigs, McKellar has brought an energy to Vancouver’s social history that few books have. He paid the price along the way but he’s really given us something here. And we haven’t heard the last from McKellar. He has more fascinating projects in the pipeline.

For now, we should all buy his book.

*

Grahame Ware wrote his first poem in 1965 as a sixteen year-old shortly after buying Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited at Kmart. The central image of his opening foray into verse was “a reluctant wolf in an uncomputered spaceship.” Talk about alienation! He’s had an abiding interest in poetry ever since, and lists Gwendolyn McEwen as his favourite poet. The teachers with the most influence on him were the integrative semiotician, Tony Wilden, and Stanley Cooperman, the vibrant poet and SFU prof who took his life in the 70s. He admits to being with Marty that night at the Joe Mock event at Classical Joint. A collection of short stories and essays, My Private Countries, is soon to be published. He lives on Gabriola Island with his partner. He also carves and sculpts: see www.phantasma.ca

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#449 Keith McKellar’s Vancouver”

Comments are closed.