#254 Theresa Kishkan’s orchard

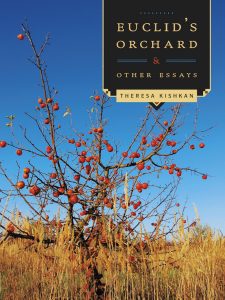

Euclid’s Orchard and Other Essays

by Theresa Kishkan

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2017

$22.95 / 9781896949635

Reviewed by Catriona Sandilands

First published Feb. 27, 2018

*

My kitchen, on this wet, early January afternoon, is saturated with the smell of apples slowly reducing to become apple butter. In the almost-forgotten autumn, my daughter and I picked about 50 lbs of Egremont Russets on a hot, sloped orchard.

My kitchen, on this wet, early January afternoon, is saturated with the smell of apples slowly reducing to become apple butter. In the almost-forgotten autumn, my daughter and I picked about 50 lbs of Egremont Russets on a hot, sloped orchard.

Many lunches, baked apples, crumbles, and exactly one tart later (my pastry skills leave something to be desired), we are ready to bid adieu to the russets’ nutty, not-too-sweet white flesh for another year and consign the rest of them to preserves. Wafts of clove, allspice, cinnamon, and nutmeg mingle with apple and draw us into the smell of winter.

For about the length of time that it has taken to reduce the apples to an appropriately spreadable thickness (nearly two hours), I have been trying to make headway into Euclidean geometry: pure math, like pastry, is something that I find beautiful but elusive.

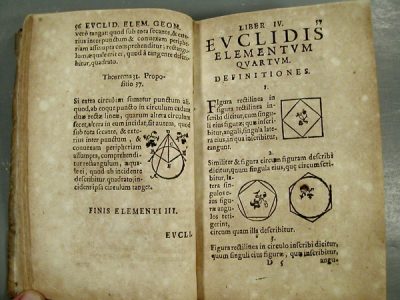

Specifically, I want to understand Euclid’s orchard, which is a thought experiment that involves identically-sized trees placed on lattice points in a square lattice. If you stand at the origin of the lattice (the bottom left tree in the orchard/quadrant), Euclidean geometry allows you to predict which trees on the lattice you will be able to see directly, and which will be obscured by other trees. It turns out that each of the trees we cannot see is blocked by the one that its numbers reduce to, meaning that all of the trees that are visible have coprime coordinates, and the ones that are not visible do not.

At least, I think that’s right. Just when I feel I have a solid grasp of the trees and the lattice and the relationships, and just as I am poised to glimpse the larger truth about the world that the thought experiment reveals, the understanding recedes from my grasp. I am left with longing: I know there’s something foundational about the pattern, but I can’t quite touch what it is. The helpful youtube “geometry explained” videos can’t interpret my longing for me, and it continues to resonate underneath the sounds of the apple butter jars in the hot water canning bath.

Theresa Kishkan’s beautiful essay collection Euclid’s Orchard is very much concerned with the pursuit of pattern and meaning, and also with the elusiveness of geometric clarity in the midst of the dense particularities of places and relationships (obviously, it is why I am wrestling with Euclid in the first place).

The back cover blurb describes the book as “an intricately patterned algorithm, a madrigal of horticulture and love.” I like the metaphors, but I am not sure I entirely agree with them; for me, the book is also about the stubborn refusal of life to conform to even the most elaborate logical or harmonic structure.

Although the final essay, “Euclid’s Orchard,” thinks with several different mathematical concepts in order to explore the intertwinements of trees, coyotes, and generations of a family — Euclidean axioms and postulates, Pascal’s triangle, and most beautifully the Fibonacci numbers that are so abundantly manifest in the natural world — the overwhelming sense of the book is that attentive presence in the world requires “departing from … logical usage to urge the reader to emotional and intellectual discovery” (p. 153): looking, sideways, at the trees we otherwise can’t see.

Many of the essays in the Euclid’s Orchard are intensely personal, and the intensity becomes most heated when Kishkan is writing about her fraught relationship with her parents, especially her father. The book’s first essay, “Herakleitos on the Yalakom,” written in the second person to her (dead) father, is so personal that it is almost painful to read: It is a daughter’s frank letter to a very difficult, sometimes downright hateful parent who is more concerned with knives and fishing tackle than the affections and aspirations of his daughter and sons.

For his children and grandchildren, his is a “legacy of diminishment” (p. 7). Later in the book, Kishkan softens slightly by allowing into her relationship with him the fuller family picture of brothers, mother, and the different places where they lived when she was a child.

In “Poignant Mountain,” for example, set in Ridgedale where he worked at CFB Matsqui, his violence is still present, but only as a small, almost matter-of-fact moment in her rich depiction of the tastes, smells, sites, and events of her remembered life there: the sharp taste of buttermilk and the creamy yellow of pancakes from neighbouring farms, a prank played on her by her brothers (in which they locked her in a below-ground dairy bunker), a baby shower full of cigarette smoke and fur coats she attended with her mother, even the bridge over the Fraser river from Matsqui to Mission, from “the open prairie to the shadow of the mountains … from the dailiness of our lives … to the lights of Mission City” (p. 95).

Kishkan also softens toward her father by giving him a context in the struggles of his parents, poor immigrants from what is now the Czech Republic, to make a life for themselves and their surviving child in the harsh, dry landscape of Drumheller in the early twentieth century. As she discovers on a trip to the Alberta Provincial Archives, her paternal grandparents were not, as she had thought, homesteaders: her father “never knew or never told that the family home was a shack in a former squatters’ settlement” (p. 60).

Kishkan also softens toward her father by giving him a context in the struggles of his parents, poor immigrants from what is now the Czech Republic, to make a life for themselves and their surviving child in the harsh, dry landscape of Drumheller in the early twentieth century. As she discovers on a trip to the Alberta Provincial Archives, her paternal grandparents were not, as she had thought, homesteaders: her father “never knew or never told that the family home was a shack in a former squatters’ settlement” (p. 60).

The madrigal of the essay “West of the 4th Meridian: A Libretto for Migrating Voices” includes the imagined words of her grandmother, her grandfather, and his brother alongside her father’s curt responses to Kishkan’s questions, alongside her children happily having babies and announcing pregnancies, alongside both her memories of family gatherings and her present experiences of the prairie.

Paired with “Tokens,” a parallel essay about her mother’s complicated relations to family told through the stories of some of the tangible things that mark a parent/child relationship — artifacts, heirlooms, papers — it is a particularly powerful reflection on both the presences and the absences that make up family histories: ghosts, “blurry moment[s]” (p. 78), and especially the intrusions of the concrete present into the ephemeral past that reorganize memory through the persistence of photographs, coats, chest, and buttons.

Euclid’s Orchard is, of course, full of Kishkan’s signature: arresting descriptions of the material details of place and inhabitation; her home on the Sechelt Peninsula; her responses to the places through which she is travelling as she reflects on her family across five generations; and of course her orchard, lovingly planted and eventually failed in the face of the deer and bears that have, in the end result, a more vigorous claim to the harvest than she does.

Each image is a perfect crystallization of a detail, gesturing toward a truth much larger than the tiny pinpoint of its composition. Near Victoria, she recounts an exquisite memory of “an abandoned house completely knitted into place by honeysuckle and roses” (p. 101). Near Drumheller, she sings the prairie: “turn, turn, bend the song to the roadside plants … free verse composed of craneflies, dragonflies, bluebottles, broad-bodies leaf beetles, greasewood and cocklebur” (p. 61). And near her home, she concludes with the cries of coyotes: “lilting joyous youngsters unaware that a life is anything other than the moment in the moonlight, fresh meat in their stomachs, the old trees with a few apples and pears too small and green for any living things to be interested in this early in the season” (p. 155).

At the end of the day, the patterns may be intricate and exquisite, but it is the unpredictable, intimate details of the past and present that create a life: a father’s fishing knife, a mother’s new suit, a grandmother’s hands, the anticipation of an egg salad sandwich, a cherished family wisteria by the west-facing deck.

After searching for the meaning of Euclid’s orchard, sometimes the most important thing you are left with is the smell of apples cooking in your kitchen.

*

Catriona (Cate) Sandilands is a Professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University, where she teaches at the intersections of environmental literature, humanities, and philosophy; queer, lesbian, and feminist studies; and ecological politics (especially but not only in BC). The author of close to seventy articles (academic and not so academic) on topics ranging from national parks to lesbian communities, Walter Benjamin to honeybees, melancholic natures to monstrous plants, she is probably best known for The Good-Natured Feminist: Ecofeminism and Democracy (Minnesota, 1999) and Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire (Indiana, 2010). She is currently working on two projects, the first a reflective monograph on Jane Rule’s public lives as represented by her novels, stories, essays, epistolary activism, and community engagements, and the other a collaboratively produced collection of stories, memoirs, and poetry on climate change centred on the Salish Sea.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “#254 Theresa Kishkan’s orchard”

Comments are closed.