A ‘dream on the water’

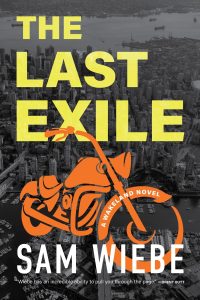

The Last Exile: A Wakeland Novel

by Sam Wiebe

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2025

$24.95 / 9781998526086

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

Detective Chief Inspector Adam Dalgliesh, London’s cop-poet, appeared in print in 1962 and effectively retreated from public life in 2008, having solved, or tried to solve, cases in thirteen subsequent novels. Detective Inspector John Rebus strode the mean streets of Edinburgh through about two dozen novels. He retired in 2024. The creations of P.D. James and Ian Rankin, respectively, each character stands for the singular creative talent and sobering worldview of an author whose publications have attracted legions of readers. For fans, numbering in the millions, the question is virtually never “Is the novel any good?” for the simple reason that the quality is assumed: of course it’s good. The real draw of the latest instalment is following a case—the tense relationships, the grisliness, the suspects, the twists and turns, the ambiguous resolution—relayed via masterful hands.

Though a relative novice with a handful of novels under his belt, New Westminster author Sam Wiebe has fans in sizeable numbers. And for good reason. Like James and Rankin, Wiebe has earned admiration for a signature style. There’s a propulsive tough-guy prose that’s artfully spare. Cases where apparent simplicity (a missing person, a dead body) gives way to beguiling complexity. Investigators with their own intriguing complexity. Plus, an expressionistic portraiture of the west coast that’s nostalgic yet critical, not to mention jaded, despairing and angry, but also affectionate. Disturbing too, as the region’s underbelly, a festering corruption that’s endemic to the human species, isn’t limited to a little x on a map. It’s anywhere. Or maybe everywhere. Wiebe’s Greater Vancouver Area gives Gotham a run for its money.

Readers will be right to assume that The Last Exile, Wiebe’s latest novel, is good. Sentence by sentence, he exhibits a steady hand; and chapter by chapter he showcases a brain for criminal puzzles. Plus, from start to finish, there’s that painterly gift for observation.

After the superb Ocean Drive, where White Rock-based RCMP Staff Sergeant investigates a horrific, metastasizing case of arson, Wiebe returns to Dave Wakeland in The Last Exile. The PI was last seen battered, guilt-ridden, bone-tired, and sick of it all (yet: in love) in Sunset and Jericho, where he readied himself for new scenery in Montreal. The Last Exile catches him for a brief moment in Montreal, where although retired and “practising radical indifference” (aka “boozy idleness”), he remains ill at ease. A call from Vancouver that begins with “I need help” cuts short Wakeland’s “reprieve.” His ears are filled with “get the hell back to work.”

Wiebe doesn’t launch the novel with Wakeland, but with a celebration. On a float home docked at Granville Island, a woman and man return home on an evening of toasting to a forty-year anniversary. Their “dream on the water”—affluence, contentedness, ease—ceases in a heartbeat: a panicked thought—“alone here, now, at the end of the world”—accompanies fear, screams, and the sight of a woman carrying an axe. In that prologue, Wiebe draws a connection between the couple’s well-heeled comfort and their underworld connections. A key relationship of theirs involves “favours,” “unclean cash,” and the Heaven’s Exiles Motorcycle Club.

Wakeland soon meets Maggie Zito, who has been arrested for what the media calls the Houseboat Massacre. Police found a hatchet and machete in a shed on her property. An old wound originating with the death of Zito’s brother and the woman’s reputed appetite for vengeance suggest an open-and-shut case.

Nothing is so easy, naturally. Wakeland’s preliminary steps remind him of the ‘love you, love you not’ of his sentiments for Vancouver. He left feeling no longer at home in the place he was born, and his first few days do nothing to comfort him. One cop’s outlook—“We’re all fucked and who cares anyway. Tant pis”—immerses him far into his own ambivalence. Along the way sights, from the “elegant emptiness” of Yaletown to a solitary man smoking crack on a park swing, find Wakeland mulling over the city and coming up short on accolades: “The days of an honest living were over. The new frontier involved corporate pillaging, jicama slaw, and a view of construction cranes from a 300-square-foot micro apartment. Don’t care for a million-dollar mortgage? You’re free to leave. Again.”

Even the business he ran with Jeff Chen has stumbled into staggering debt. Jeff himself appears dissolute. Worse, perhaps, is a case that brings Wakeland in contact with—and later, a Faustian relationship with—a nemesis, a guy who “was volatile and brutal, enjoyed hurting people, adored being feared.” Despite dread, despite uncertainty, and despite ambivalence and a thriving sense of fighting an uphill battle, Wakeland proceeds. Even though there might not be much justice left in the world, he’ll do his part to maintain order. Besides, in the Zito home he perceives an essential part of Vancouver that has been mowed over by yoga wear moguls and e-commerce czars. If he can keep that nurtured, thinks Wakeland, he’ll be doing an unqualified good.

Naturally, Wiebe shows that notions like doing the right thing aren’t necessarily directly applicable to real life, or the Vancouver of his novels, where “every evil leads back to real estate” and “you ingest small does of loss every day.” As the case intensifies (oh boy, does it) Wakeland faces old demons even as he strives for presence in a fledging romance and calm with a beleaguered former partner, who tells him, “Get gone, Dave…. Get fucking gone.”

Although a “man with a code” (cracks the PI’s jailed sister) who resides on “a whole continent of stolen real estate, floating on the dead and dispossessed,” Wakeland finds a place for himself on the final page of The Last Exile. He may have made peace with his own personal Mephistopheles, and perhaps gotten the better of him. For the time being, at least. Wiebe knows about deals with the devil, though. We’ll have to wait another two years to learn what price Wakeland will have to pay.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, published in 2021 with Now or Never Publishing, is reviewed here by Geoffrey Morrison. A previous novel, Oldness; or, the Last-Ditch Efforts of Marcus O (2018), was reviewed by Dustin Cole. [Editorial note: A BCR editor, Brett has reviewed books by Maureen Young, Daniel Anctil, Adam Welch, Andrea Bennett, Patrick Grace, Cole Nowicki, Tania De Rozario, John Metcalf (ed.), Brandon Reid, Beatrice Mosionier, Hazel Jane Plante, Sam Wiebe, Joseph Kakwinokanasum, Chelene Knight, Lyndsie Bourgon, Gurjinder Basran, and Don LePan for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster