A musical, musical life

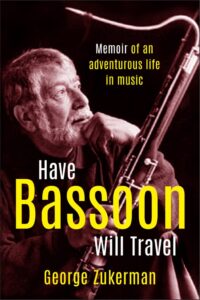

Have Bassoon, Will Travel: Memoir of an Adventurous Life in Music

by George Zukerman

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2024

24.95 / 9781553807131

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

“It was a brilliant, expensive and insane proposal. But somehow it worked out.” Sometimes a short quotation can crystallize a whole book. This isn’t that quotation. It comes close, though. In tone, language, and content, these few words go long way to epitomizing George Zukerman’s Have Bassoon Will Travel, a memoir of his musical life. A longtime resident of White Rock until his death in 2023, this unstoppable and multi-talented man of music describes his two musical identities as “impresario and virtuoso.” In one of his obituaries, that list is given a third component—“raconteur.” Anyone emerging from the end of this utterly absorbing book will have a hard time disagreeing that all three are equally accurate.

The subtitle of the book, “Memoir” (in white) and, as a qualifier, “of an adventurous life in music” (in yellow), goes a long way to getting it right. In some ways, though, the memoir is better described as “misadventures in music.” Indeed, most readers are likely to experience the whole narrative sequence, not as a life arc, but, rather, a scrapbook of incidents, many wonderfully “insane.” Although punctuated with some key autobiographical way marks, the book only touches on Zukerman’s personal life and, in particular, his two marriages, the first unhappy, the second rewardingly happy. The fact that Zukerman’s written sketches were assembled into book form by a “small group of ‘co-conspirators’” rather than the author himself explains some of the effect, but only some: this is a remarkable life that really seems to have been a series of stories—and mighty good stories.

Ironically, perhaps, with no claims to being an autobiography, and with almost no writing that approaches self-portraiture, the memoir nevertheless conveys a vivid sense of a memorable personality. (Accurate? We cannot know for sure.) This indirect portrait is created in three main ways—first, through the decisions and actions Zukerman undertakes (remarkable); second, through the language with which he writes about those decisions and actions (likewise remarkable); and, third, through the ways others react to some of his astounding, even preposterous undertakings (spoiler alert: usually vigorously, often positively). A single sentence in the “Postlude” reveals a lot: “I simply cannot stop planning, dreaming, imagining… and hoping that somebody will sense the excitement and potential in such projects.” And the impression created of an extraordinary personality is all the more extraordinary because he usually doesn’t seem to notice how extraordinary he is.

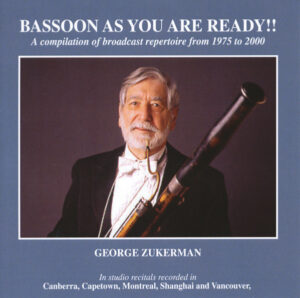

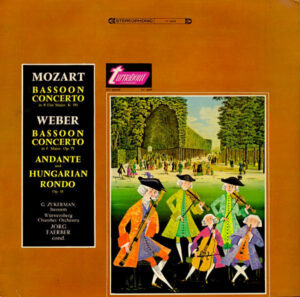

True, at a few points Zukerman rises to expressing something like avuncular pleasure in some of his achievements. Being, for example, the first western solo bassoonist in the Soviet Union or arranging literally hundreds (and hundreds) of concerts in the tiniest villages in Canada’s far north are, after all, no mean feats. Still, the recurring note is of self-effacing breeziness. In one case, for instance, after playing the fiendishly difficult solo opening to Stravinksy’s Le Sacre du Printemps—in front of the composer—he writes, “I suppose it must have gone passably well.” We all suppose likewise: the great man chatted amiably with the author after the performance, leaving him “awestruck that the composer had deigned to talk to a mere bassoonist….” From a broader perspective, it is striking that he lets slip only a line or two about his commercial recordings and never breathes a word about being awarded the Order of Canada, or any other of a proper slew of further distinctions and medals.

On the contrary—he revels in stories where he is the anti-hero. His description of his role in the navy is typical: ”Apart from the fact I never succeeded in repairing whatever it was that ailed the antennae, my seasickness aloft became so severe that I was finally released from service at sea and deposited ashore….” Not only does the author usually underplay his own cleverness, creativity, and courage (or is it audacity?), but he almost always seems good-humoured. Almost. At a a few points he seems wickedly delighted to rise to just the teensiest bit of dudgeon—when, for example, he recalls acting on behalf of the musicians of the Vancouver Symphony and, as a result, being let go by the management for having been a “troublemaker.” As for the CBC, it does actually get something close to a tongue lashing for shutting down the CBC Radio Orchestra, “in an inexplicable act of musical destruction.”

In both these examples, Zukerman is clearly devoted to the value of music, even though he writes few passages where he rhapsodizes about performing. The few that he does write are memorable. As a young man, for example, as he says, “I was helplessly caught up in transcendental awe at the miracle and wonder of ensemble playing.” As a solo bassoonist he describes the intensity of sustaining a long note: “you may experience ecstasy or ‘exquisite pain’ in a moment of achieved beauty.”

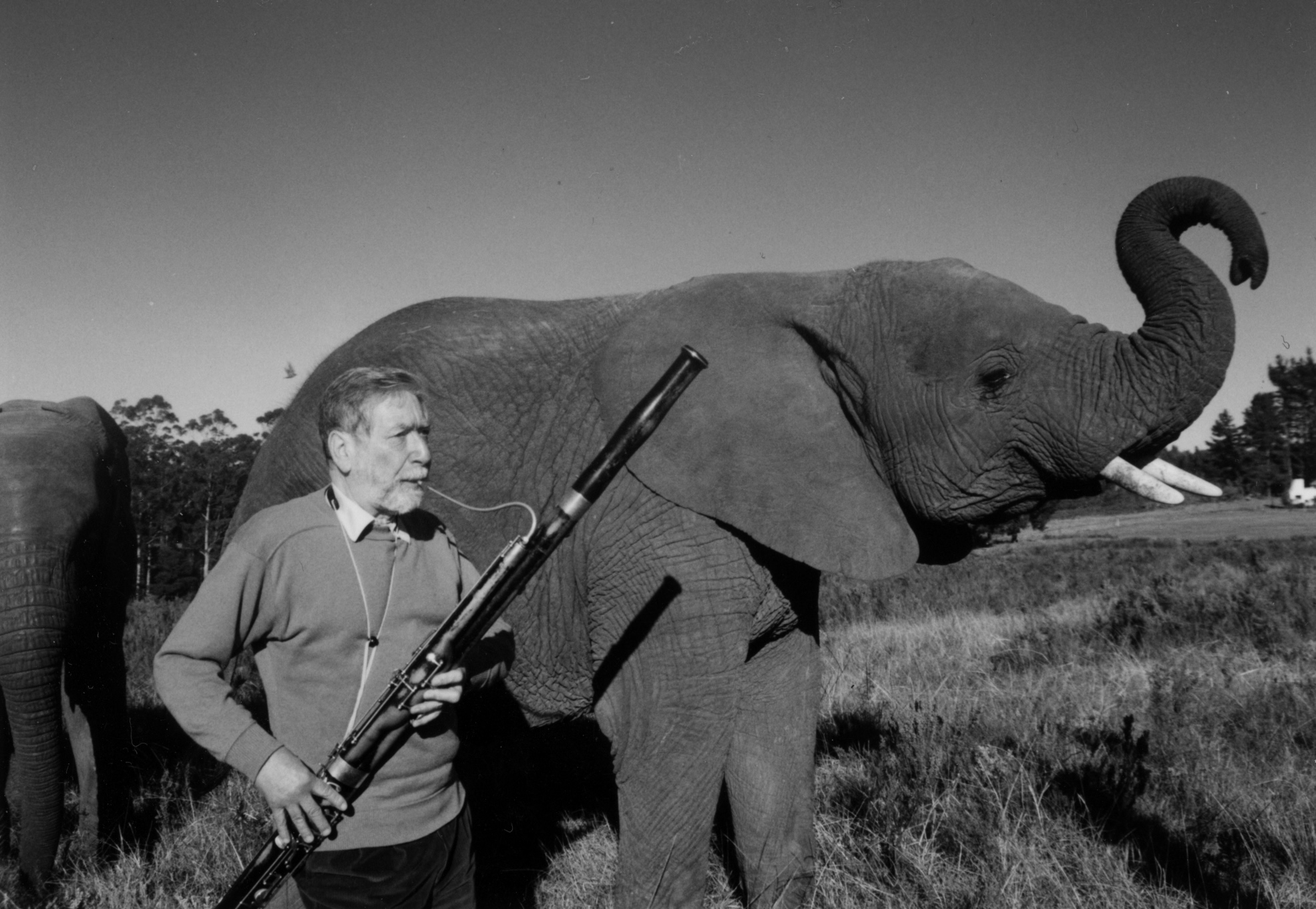

Zukerman’s personal relationship with music has a sharper focus, though. More than just a musician, he was a bassoonist—and, as such, “did my best to free it from penal servitude in the back ranks of the symphony orchestra.” The barriers were huge. To get out of the “back ranks” a soloist would need, unsurprisingly, solos. Getting them required numbing willpower and effort. Penetrating the recesses of obscure music libraries and tolerating dour gatekeepers, Zukerman ultimately ended up with “170 works that I discovered and transferred to film, or wrote out laboriously by hand….” Thus armed, the bassoonist achieved huge international success—even being compared, as he notes with amusement, to rock guitarist icon Van Halen.

But, as he says, he had two hats—or, as he puts it sometimes, he operated by a toggle switch. Switch the toggle and suddenly he is no longer the “virtuoso,” but the “impresario,” the originator in Canada, for example, of a vast network of far flung community concerts. Operating on a system of financially fail-proof subscriptions, this he called the Overture Concert series. In addition, through the force of sheer personality, we sense, he managed, amongst other projects, to engineer enough grants to take music to the remotest northern communities.

Far from financially fail-proof, this kind of outreach could lead to his recalling of one case, apparently as pleased as Punch, “our budget was splendidly shattered, but we had made some kind of broadcasting history.” He is equally pleased to report that one (good-hearted) administrator called one of his tours “Zukerman’s Folly.” While most readers will be puzzled that the bassoonist seemed to be equally fulfilled playing the “theme song from The Simpsons” to a tiny audience of Innu as performing a concerto with a major symphony, his joy in this kind of performance is also deeply considered. Only too aware than most southern interventions in the north were “patronizingly instructive,” he, through “the glory of music,” did not “impose a preconceived order.” The music he brought was simply “to listen to, to marvel at, to emulate, to enjoy or—equally—to reject.”

No matter which way the “toggle” was switched, though, the author, through his recollections, consistently wears the third hat identified by his admirers—that of “raconteur”. Anyone dipping into the book at just about any point will instantly be absorbed. From just about any incident, the author manages to extract and emphasize the most colourful details and, through splendidly flamboyant language and vividly cadenced sentences, to construct a whole drama. In simple terms, for example, he witnessed a raid on a restaurant in Tel Aviv that served forbidden foods. Those are the simple terms. Zukerman’s terms are quite otherwise: as he puts it, he saw “happy diners… attacking their schnitzels and savouring succulent mouthfuls,” until panicked waiters, in reaction to “furious hammering,” seized “plates from under diners’ noses and carried them relentlessly out of sight,” with some “half-consumed meals left behind as congealing evidence of gastronomical crime.” Extravagantly written? Of course. Delightful? Richly.

Even without turning to such language, the author, with a razor sharp eye for recollected detail, can make vividly recalled circumstantial details dance off the page. At one tiny village in northern Ontario, for example, he places the fascinated reader directly into a “dilapidated shed that served as the terminal building. There was a solitary pay phone but it was clearly out of order, its wires ripped from its base. Torn airline posters clung precariously to the wall. On the desk which once served as a check-in counter, were faded travel posters of the Spanish Riviera and a typewritten page of stern instructions about proper hygienic disposal of sickness bags.”

His love of puns adds to the energy: “Who else in the world could possibly claim to have played Rigoletto in Rigolet?” he asks. (And, for those who don’t know, Rigolet is a village in Labrador.) His parallel love of going beyond actual events and spiralling into the world of whimsy can lead to a preposterously straight-faced assertion like “‘Yes,’ breathed the victorious cheese….” Further to add to the narrative joy, the memoir is divided into bite-sized morsels, alive with titles like The Bail Bond Bassoonist or Piano in the Passing Lane.

As for the stories themselves, though, patterns and themes emerge, without apparent design, but certainly with unifying effect. One of the most revealing could arise only in the memoirs of such a well-traveled and observant writer—namely, striking cultural practices. It might, in one case, be in the form of his discovering that Chinese composers typically chose a florid, sentimental style of music and to disguise forbidden traditional tunes by giving them titles like “Chairman Mao’s Triumphant March to Victory through the 7th Valley of the Yangtze River.” This is, we are assured, completely true. Likewise, Zukerman might be astounded that the entire audience of the Glinka auditorium in the Soviet Union rose to their feet before he played even a note. Why? Well, as he later learned, he happened to be playing a composition by the very Glinka after whom the auditorium was named. Standing, in such circumstances, was what one did. Who could have known?

Even within Canada, the cultural moments never stop coming. In the far north, for example, it might happen that an audience, rather than sitting passively, “came with their own musical instruments: a fiddle, an accordion, the ubiquitous drums. Sometimes they played with us. On one occasion they came up and challenged us to a throat-singing competition.” Characteristically, Zukerman cheerfully observes, “We lost!”

A second recurring theme in the swarms of stories, is colourful characters. They abound. They might be famous composers like Benjamin Britten, Aaron Copland, or Dmitri Shostakovich. They might be other celebrities, like Roger Bannister. Of all of them, probably the most admirable is a eccentric and irascible master bassoon repairman. At the opposite end of the likability scale is the notoriously difficult conductor Herbert von Karajan. As Zukerman carefully presents the man, his notoriety was well deserved. A more thoroughly unpleasant man, it seems, there never was.

The most permeating theme of the most memorable stories is the fact that so many of them turn on the way that things can, and often do, go horribly, horribly wrong. While every book needs a villain, in this book the human villains are few. When they do occur, they do so most often in the form of bureaucrats and officials. Cue, for example, the grim officials in Moscow airport who conduct a “quasi-inquisition,” abetted by “snarling Dobermans.” Or take the border guards (there is a sub-theme here) who refuse to allow a desperately late group of performers to get to their concert—because their car is rented. Probably the prize for the most bizarre of these officials we encounter in the royal library of Madrid. As Zukerman reports, without batting an eye, “my cufflinks were confiscated lest they contain hidden cameras. Only then was I grudgingly permitted to copy by hand, from the library’s immense collection…. for hours I sat under the constant watchful scrutiny of two members of the Guardia Civil, suitably armed with automatic weapons pointed threateningly in my direction.”

In response to many an officious roadblock, though, is, in many stories, a mighty array of arm waving, voice raising, bargaining, cajoling, and sweet-talking. Sometimes aided by others, often alone, the author more often than not gets his musical way. In attempting to get North American soloists to get paid in hard currency for performing in the USSR, for example, he proposes intricate solutions until, eureka, “details of a compromise were tortuously hammered out.” Some of the compromises, though, are worthy of the most preposterous comic film. At one point, a giant cheese (in, of course, Zukerman’s possession) is refused entry onto an airplane. The eventual solution? It is cut in two, half in Zukerman’s hand-baggage compartment, half fed to the fellow passengers as part of their meal.

The biggest villain of the piece, though, and perhaps the most recurrent theme, is not human. It is the weather. More than anything these stories record a battery of snow storm after snow storm, canceled flights, blocked roads, panicky diversions and desperate countermeasures, even if they might involve “war canoe, bombardier Ski-Doo and… dog sled.” Snow storms aren’t always the culprit: “we spent the next three hours driving through swirling clouds of dust and sand, looking for overnight accommodations.”

On the opposite side of the scales and the most heartening theme is the one that emanates from good will—and the extraordinary number of times a motley array of townsfolk, minor officials, just about anyone in a position to help, rises to the inventive and surprising occasion. The show does, in the end, nearly always go on. In one example, “What followed then was a miracle of community organization. The editor spoke to his son, who spoke to his friends at the high school who spoke to the principal, who spoke to the mayor, who spoke to the librarian, who happened to be married to the town’s hospital administrator… and from this exchange came an extraordinary plan.”

This goodwill is nowhere more common than in getting musicians instruments on which they might play—not necessarily their own, but instruments nevertheless. The title of the section called Flying Pianos perhaps says it all. But, while pianos, in story after story, are probably the most problematic, they are not alone: “where on the Canadian prairie,” asks the author, “would we find four concert harps in the next twenty-four hours?” Even the bassoon could create a crisis, not least of all when the author is expected to play an original composition, by Canadian composer Murray Adaskin. On sight. Without a bassoon: “A borrowed high school bassoon appeared complete with three ancient reeds—one caked solidly with lipstick, one cracked down the middle, and a third that was made barely playable after ten minutes of ardent scraping with a borrowed kitchen knife.”

Another crisis averted. Another Canadian composition introduced to the world. Yet, whether introducing the world to an original Canadian composer, as here, or evoking The Simpsons, whether performing in a giant concert hall full of the glitterati, or organizing the world’s tiniest concert for five villagers, George Zukerman conjures up an unforgettable experience for the reader as much as, we sense, he did for countless music lovers. How did he accomplish all this? As he puts it in the opening sentence, “Somehow it worked.”

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at UVic and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, UVic, and finally Lester Pearson College in Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at Banff School of Fine Arts and UVic. He lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Theo Dombrowski has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has reviewed books by Robert Mackay, Genni Gunn, Eric Jamieson, Adrian Markle, Tim Bowling, Lisa Brideau, Deborah Willis, Brady Marks and Mark Timmings, Darrel J. McLeod, and Max Wyman for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “A musical, musical life”

My goodness! This must be one of the most thorough and enthusiastic book reviews I have ever read. With a summary like this, my only hope is that the reviewer, like some movie trailers, did not divulge all the best parts. I shall find out for myself when reading Have Bassoon, Will Travel! Thank you for this thoroughly provocative review.

What a terrific, thoughtful, insightful review. Ordering the book now!