A foundling in the stacks

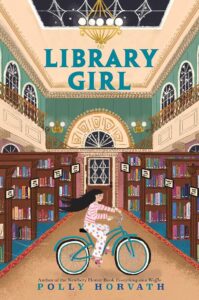

Library Girl

by Polly Horvath

Toronto: Puffin Canada, 2024

$22.99 / 9781774883341

Reviewed by Greg Brown

*

Polly Horvath’s Library Girl, her latest middle grade novel, reads like a forgotten classic. It follows a plucky orphan raised in unusual circumstances; the antagonist inspires more giggles than terror; and the omniscient narrator reads like a refreshing anachronism in the sea of first- and third-person limited narrators that abound in contemporary fiction for young readers. When it works, Library Girl is almost endlessly charming, evoking the warmth and kookiness of The Wind in the Willows or Pippi Longstocking. When it stumbles, it reminds you why we don’t teach Homer Price in schools anymore. (Too episodic for young readers raised on the rollercoaster excitement of Rick Riordan novels!)

There’s a fine line between classic and old-fashioned that the book can’t always keep straight. It’s the kind of kids book a parent—or more likely a grandparent—would love, and a young reader might only just like. Still, Horvath, who resides in southern Vancouver Island and has published some twenty books for kids, including Everything on a Waffle (a Newbery Honor book) and The Canning Season (winner of a National Book Award for Young People’s Literature), knows what she’s doing. The novel is fanciful and fun, even though it occasionally stalls out.

In the novel’s opening chapters, the narrator introduces four eccentric librarians—Doris, Lucinda, Taisha, and Jeanne-Marie. They work in the children’s section (except for Lucinda) of the Huffington Public Library, a lovely, red-bricked building with “scrollwork aplenty.” These eligible bachelorettes are fast friends and share a secret longing. For years, they’ve each pined for a baby. And, like in a fairy tale, they discover one: a foundling abandoned in the stacks. They plan to bring it—her—to the authorities, but of course they don’t. Within a week, they’re on a rotating schedule, caring for the child in an inner office. Technically, it’s kidnapping. But also: love.

The child, dubbed Essie, grows up under the care of her four mothers. They go to elaborate lengths to hide her from “shy and devastatingly handsome” Mr. Fellows, the befuddled head of the library—and later from Ms. Matterhorn, yet another librarian and the novel’s busybody antagonist who vows to kick Essie out of the library for good, having taken her for a vagrant. (Understandably, as Essie’s always hanging out in the library!) Meanwhile, Essie bathes in a tub lugged into a cramped office and receives improvised schooling from her four-headed materfamilias. Better yet, she spends days reading—and reading well. She gobbles up Shakespeare and then plays by Edward Albee and Tennessee Williams. By age eleven she’s enjoyed a “splendid education” and plans to continue reading until she’s read every book in the main branch.

There’s a madcap energy to all this setup, a silliness that calls to mind the baroque playfulness of Wes Anderson or Anderson’s greatest influence: Roald Dahl. Realism this ain’t. (Not even by the loosey-goosey standards of children’s literature.) It’s delightful, though it often feels more like tableau than motion. Nothing much happens in the first several chapters. There’s no real sense of urgency. The problem rests with Essie, and the novel’s failure to give her a meaningful problem. Yes, she’s grown antsy to explore the world outside the library, and visits a few local shops, including Hippy Haven, where she disperses her allowance on candy and bath soaps. But it’s a pretty banal vision of freedom and doesn’t inspire much dramatic energy. Hard to imagine a young reader caring about Essie’s first fumbled trip to the store.

Things eventually pick up when Essie befriends G.E., a familiar-looking boy whom Essie believes is her long lost twin. He’s a bit of a bad egg—and certainly a bad influence. He claims he’s also an orphan like Essie and that the three appliance salesman and surly cook he’s been hanging out with are actually his four dads. Essie and G.E. (named, Essie believes, for General Electric) hatch a harebrained scheme to trick their eight parents into falling in love. It’s The Parent Trap multiplied by four. And it’s here—in this late arriving plot—where the novel finds its footing and where Essie finally finds something worth chasing. The novel achieves lift-off and there’s a sense of momentum, as the wound spring of silliness finally snaps into motion.

Throughout these late developments, the novel trots out some big ideas about the gap between fiction and reality, suggesting that Essie’s biggest problem has been how badly she’s wanted her life to be a storybook, like the ones she’s grown up consuming in the library. And that’s she pushed too hard to find a Big Happy Ending for her four mommas. (Oh, how badly she wants them to fall in love with her long lost twin’s four poppas!) But there’s so much unreality in Essie’s life—her having four mothers, for instance, and the fact that she’s been raised in a library like, well, a lucky orphan in a story—that it’s hard for the reader to arrive at the same conclusion. There’s just too much artifice in the novel to take its skepticism of artifice seriously. Isn’t artifice the entire pleasure of this novel?

Anyway, the only real question is: Will a kid like this book? Will they be charmed by the strangeness of Essie’s maternal glut and laugh out loud to read the villainous villainess Ms. Matterhorn described as “one who caused cats to leap into open manholes.” Will they care about lovelorn Mr. Fellows pining after one of Essie’s moms? Sure. Maybe. But most of the young readers I know—and I teach students the age of the book’s intended readership—care about action, profluence, and plot above the kind of delights offered here. Young readers aren’t immune to whimsy and silliness. They love these things! But only when embedded in stories that move. And Library Girl takes a touch too long to turn the page.

*

Gregory Brown is a writer and teacher from Nanaimo, BC. His work has appeared in Pulp Literature, PRISM International, Best Microfiction, The Journey Prize 30: The Best of Canada’s New Writers, and elsewhere. He’s taught at the University of Virginia’s Young Writers Workshop, the Creative Writing for Children Society in Vancouver, and Literacy Central Vancouver Island. [Editor’s note: Gregory recently reviewed Sarah Suk for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster