STWS? Read on.

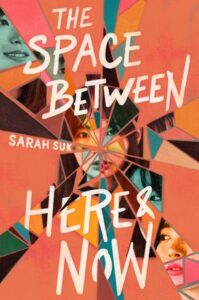

The Space Between Here and Now

by Sarah Suk

Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2023

$24.99 / 9780063255135

Reviewed by Greg Brown

*

Sarah Suk’s second YA novel, The Space Between Here and Now, is a beautiful, heartwarming story about memory and grief with a speculative twist and a sprinkling of romance that’s sure to delight teen readers. It’s soft sci-fi, or if you like, speculative fiction from the heart. The novel’s time travel conceit is big and flashy—part Billy Pilgrim coming unstuck in time, part magical memory retrieval system à la Harry Potter’s Pensieve. But that never outshines the novel’s earnest teenaged heart. This is a novel about finding yourself—wherever or whenever you are.

Protagonist and narrator Aimee Roh is a seventeen-year-old Vancouver high schooler who suffers from a rare and unusual medical condition: She can time travel. Well, sort of. She’s afflicted with STWS (Sensory Time Warp Syndrome), which causes her to vanish into her own past. One minute she’s strolling past the high school woodworking shop, the next she’s reliving a family vacation on Salt Spring Island. It’s annoying for Aimee. Who wants to disappear in the middle of a date? Awkward. Plus, there’s always the danger of becoming trapped, like a few rumoured STWS sufferers, inside a “time loop”—an endless temporal purgatory of repeating memory.

And what’s the cause of Aimee’s syndrome? Well, it’s a medical mystery, though it seems at least partly connected to the trauma of her family’s breakup. (Throughout the novel, STWS serves as an ingenious catch-all for all the ways in which we get lost in the past: grief, post-traumatic stress disorder, even nostalgia.) It doesn’t help that Aimee’s father refuses to talk about the end of his relationship with Aimee’s mom, the past, or really anything. He’s convinced himself that everything—including Aimee’s worsening condition—is fine. Repression, thy name is Dad.

The disappearance of Aimee’s mom, who abandoned the family and returned to South Korea when Aimee was a child, turns out to be the fulcrum of the novel’s plot. According to Aimee’s dad, her mom vanished “out of the blue,” but Aimee discovers, in a forgotten memory of a family vacation, that her mom’s unhappiness was longstanding. (“I can’t stop thinking about going back. Starting fresh,” her mom says, of returning to South Korea.)

There’s also a tantalizing hint that Aimee’s mom might suffer from STWS too. “You know I can’t help the disappearing,” Aimee’s mom confides. “It’s getting harder and harder to control.” Is she referring to STWS? It sure sounds like it. Aimee, anyway, convinces herself that there’s a familial explanation for her condition and talks her reluctant father into letting her go to South Korea for spring break, though crucially doesn’t disclose her plan to find her mom.

It’s probably apparent that there’s a lot of exposition in the early pages of the novel. There’s much to set up—from all the worldbuilding around STWS to the intricacies of the family drama. But once everything’s explained and settled, and the action’s been transplanted to South Korea, the novel picks up. The search for Aimee’s mom provides the story with an exciting profluence, and the double mystery of her disappearance—where is she and why did she vanish in the first place? —will keep readers hooked.

The novel’s subplots also come into view in South Korea. There’s a ghost in a subway station that may be an unfortunate soul caught in a time loop, a road trip to the countryside, and a mysterious trespasser lurking in Aimee’s memories.

Foremost among these threads is Aimee’s reconnection with Junho, an artsy boy whom she met as a kid. Of course, as any reader with a pulse will predict, a flirtation develops between Aimee and Junho. Unlike Aimee’s father, who refuses to take Aimee’s condition seriously, Junho is a gentle and compassionate listener, and really seems to get Aimee. If a bit one dimensional, at least he’s good boyfriend material. In fact, he’s not the only secondary character who might feel a bit one-note to keen readers. Apart from Aimee’s dad, whose chilliness hides a profound grief—and of course Aimee herself—many of the characters feel like they exist in service of Aimee’s story.

Throughout her time in South Korea, Aimee experiences a real sense of return. South Korea was her parents’ home when they were kids, and although Aimee’s spent most of her life in Canada, South Korea is home for her, too. Aimee’s search for her mom is actually a search for herself, and becomes an occasion for a reunion with her heritage.

The novel’s evocation of South Korea is romantic, even sensual, though also familiar and familial. (There are several scenes that take place at the table, drawing connections between food, family, and culture.) But the Vancouver author’s South Korea isn’t an outsider’s exoticization of the country. It’s a place of homecoming for Aimee. Seeing her aunt at the Incheon airport, Aimee thinks: “And then: Gomo. She is my lighthouse. Beaming at me with the light of a thousand stars.” What a welcome!

This isn’t to say that things necessarily work out for Aimee. Her investigation hits several dead ends, including a heartbreaking encounter with her grandparents. (Warning: You’ll need your tissues.) Aimee’s even tempted to give in to the allure of memory, and lets herself be carried off (maybe forever) by the recollection of a perfect day spent organizing cereal boxes with her mom. It’s not much of a memory, but it’s easy to see the temptation. Why live in the painful present when you can hide forever in the beautiful past?

Fans of Suk’s lovely debut, Made in Korea, a YA romance about two Korean American teens running competing beauty businesses, will know that Suk’s got a talent for endings. In that novel, the characters don’t finally get exactly what they want—a trip to Europe, a parent’s approval—but they do find each other, and they do grow up. Suk manages a similar trick here. Aimee’s search for her mom yields complicated truths about herself, her family, and memory. Life, she discovers, isn’t in the past. It’s here. And now.

*

Gregory Brown is a writer and teacher from Nanaimo, BC. His work has appeared in Pulp Literature, PRISM International, Best Microfiction, The Journey Prize 30: The Best of Canada’s New Writers, and elsewhere. He’s taught at the University of Virginia’s Young Writers Workshop, the Creative Writing for Children Society in Vancouver, and Literacy Central Vancouver Island. [Editor’s note: The above is Gregory’s inaugural review for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-25: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster