‘How did it get here?’

Invasive Flora of the West Coast: British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest

by Collin Varner

Victoria: Heritage House, 2022

$24.95 / 9781772034134

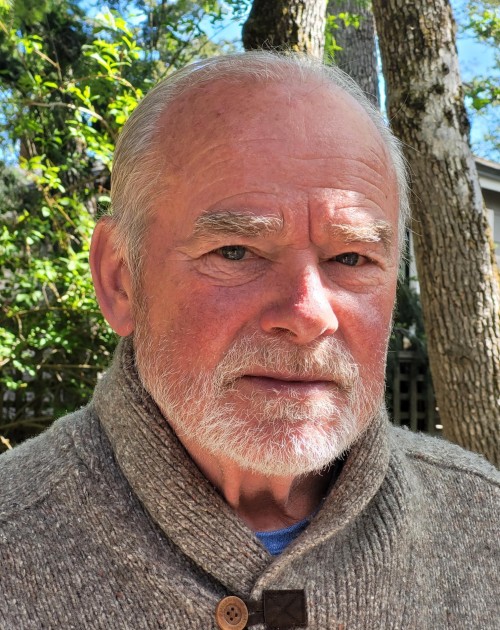

Reviewed by Dave Flawse

*

A flip through Collin Varner’s Invasive Flora of the West Coast, and everything you thought you knew about plants blows away on the wind like a dandelion puff. Varner’s book isn’t just a field guide, it will alter how you see the botanical world: invasive plants are everywhere.

An invasive plant is a non-native plant that has adapted to its new environment. Sometimes these plants outcompete native ones, but not always. Just because it’s invasive, doesn’t mean the plant is undesirable in certain contexts.

An invasive plant is a non-native plant that has adapted to its new environment. Sometimes these plants outcompete native ones, but not always. Just because it’s invasive, doesn’t mean the plant is undesirable in certain contexts.

The book is split into two sections: herbaceous plants and woody ones. As with Varner’s other field guides, each page contains a picture and lists some important details: common names, Latin name, description, traditional use, etymology, season, reproduction, concerns, and last but not least, origin.

The origin descriptions tease the reader with tantalizing snippets. Consider this one about the domestic apple: “Tian Shan Mountains, Kazakhstan. It was probably merchants working the fourteenth-century Silk Road that first spread Malus sieversii (modern apple’s progenitor) across Europe. After the fall of Rome, it was the monasteries that cared for and spread the apples, much as they did with the vineyards.” All this from the humble apple!

This is where this review takes an off-ramp. I had to learn more about these origin stories. And I’m going to share what I learned with you. I set up an interview with Varner to ask him more about these origin stories. Our conversation didn’t disappoint.

The most notorious invasives, Scotch broom and Himalayan blackberry, have been widely discussed in other places, so I asked Varner about other plants readers will likely recognize.

***

Common Apple

DF: I found the origin story of this one pretty fascinating. I had assumed the apple was a native plant.

CV: We have only one native one here. That’s Malus fusca. It’s about a quarter of an inch across. That grows along the coast here and is quite common. If you do the West Coast trail you see thickets of it. You go around Beaver Lake and Stanley Park, and our native apple is in there. But there’s 10 to 1 of the domestic apples, from people throwing their apple cores away.

And apples don’t come true from seed. You have to graft them. And that’s what happened over how many thousands of years. Romans were the first one to start grafting those. And that’s why you’ll go along the old railway lines, especially like Britain. The kids throw their apple cores out the windows. Then you wonder why there are orchards of them growing everywhere. But the apples aren’t very good.

In Vancouver they have the Arbutus Corridor. It used to be a little train that went through Vancouver off to Lulu Island, which is Richmond. That line is now a Bicycle Path, and there must be over a thousand small and big apple trees growing along that line, just from people discarding their apple cores.

When we went across Mongolia. Kazakhstan, that’s where the original apple is. That’s Malus domestica. I didn’t get to find them in the wild, but I had a bowl of them given to me, so I photographed those.

It’s amazing history on those. Think it’s only been in the last 200 years that the Granny Smith, Delicious, and all those have come out. And now the University of Washington State, they’ve been working really hard on the hybridization. They’ve come out with the Cosmic Crisp.

DF: Oh, I haven’t heard of that one. [Interjection: since this interview, I’ve tried a Cosmic Crisp: highly recommend.]

CV: To me it’s the best apple out there.

DF: Better than the Honeycrisp?

CV: Yep. It’s part Honeycrisp.

*

Canada Thistle

DF: As I understand it, this plant is native to Europe. How did it get here?

CV: It first came over to Eastern Canada from Britain by boat in a tainted seed or bale lot of hay, clover, or alfalfa. Some of these tainted or contaminated seeds or bales were sent over to Wisconsin and New York where the thistle germinated. So, the Americans called it the Canada Thistle. You know, if that would have been a good plant, it would have been called the American Thistle.

DF: How did it arrive on this side of the continent?

CV: It came across Canada the same way in tainted or contaminated seed lots or bales of hay, clover, or alfalfa.

*

Giant Hogweed

DF: The specific date of introduction in the book was interesting to me: 1950. How do you know that exact date?

CV: The seed came in as an ornamental, and it was ordered from one of the seed catalogs, and they brought it into a Seattle garden. It really is a beautiful plant. But it’s photo toxic. I ended up in the hospital when I was 12. I took down half acre of it with a machete up in Prince Rupert. The sun came out and I was in the hospital for three days. It was horrid.

One time, I measured a 14-foot-high clump down at Jericho Beach, which by the end of summer was all gone. The parks board came in and removed it. I think it was an overreaction, really.

DF: Why do you think it was an overreaction?

CV: Unless you’re going there and cutting it down and getting the juice all over your body and it’s a sunny day, it’s fairly innocuous. I will not grow it in my garden only because I’ll get shunned by the neighbours.

*

Morning glory

DF: It’s hard to miss morning glory, those beautiful flowers that are roadside, in gardens, and—

CV: Everywhere. We have a native species here that grows on the beaches. But the rest of them came over in seed lots. Most likely the big flowering one, Calystegia sepia. This is probably brought over as an ornamental because it is quite beautiful. It’s one of those ones that if it’s contained, it’s just fine.

DF: What surprised me was the line in the book that said it is one of the top-ten most-invasive plants worldwide.

CV: Yeah, they call it bindweed because it does bind all the other flowers and everything around it together. And they did use it as cordage to wrap up the hay bales at one time. So, it does have a purpose.

DF: And how do you feel about Morning Glory? Similar to Giant Hogweed or do you have a different viewpoint on it?

CV: No, it’s nasty in fields once it gets in there. If you got a damp, low-basin field, it’s horrible to get rid of. It ruins crops, there’s just hundreds of millions of dollars a year wasted on chemicals to get rid of this stuff.

*

English Ivy

DF: When you look around English Ivy is everywhere.

CV: And it’s in the top ten noxious weed. People think they strangle the trees and kill them. They don’t. They smother them. They knock out the light, and that’s what kills the trees, especially conifers.

Conifers can’t outgrow their natural shape. Whereas as a big leaf maple or birch, if they start getting English Ivy (If you want to call that. It’s actually Persian ivy. Another misnomer.), they can actually grow their limbs to get away from the ivy. They know what’s going on. And you’ll see one limb going about 30 feet sideways. It’s very seldom you’ll see one of our native maples be killed by it.

But Doug firs and our grand firs and hemlocks, they can get taken over. But a mature Douglas fir, there’s nothing that can get up to 200, 300 feet. Even the English Ivy can only get up to about 80 feet. I’ve climbed a lot of trees and gone up and looked at the ivy, and it’s pretty interesting: if the bark is really thick and has got crevices, the ivy actually re-roots and starts to regrow again at 60, 80 feet.

DF: This is a question I’ve always wondered, if people disappeared tomorrow, what’s going to happen with the English Ivy in the in the forest? Is it going to take over, or is it going to be impeded by something?

CV: Wouldn’t it be nice if we all disappeared?

DF: I know, right?

CV: The English Ivy can go ballistic as it wants. But really, the first forest fire that comes along, they’re gone. They are not used to forest fires like a lot of our indigenous plants. There is a dozen of our native plants, like fireweed, that have their seeds on the ground, and the forest fires come through and then they thrive. The seeds germinate.

Whereas the English Ivy, those seeds get burned right to toast. So, I would think you’ll have isolated spots of the English Ivy, but it will never become prolific.

DF: Thanks, Collin!

***

To learn more of the fascinating world of invasive plants, check out Varner’s latest book!

*

Dave Flawse is the publisher of a Vancouver Island history site, a freelance writer, and an editor. He writes about history, but also other lesser-known, remarkable stories hiding in plain sight. A firm believer in literary citizenship, he promotes and furthers literary arts in British Columbia with the goal of helping this robust and diverse community impact as many readers as possible. Read his portfolio here and visit his website here. Editor’s note: Dave Flawse has also reviewed books by Cathy Converse, Vickie Jensen, Kathryn Willcock and Kelly Randall Ricketts for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “‘How did it get here?’”