Broadening our thinking on grizzlies

Grizzly Bear Science and the Art of Wilderness Life: Forty Years of Research in the Flathead Valley

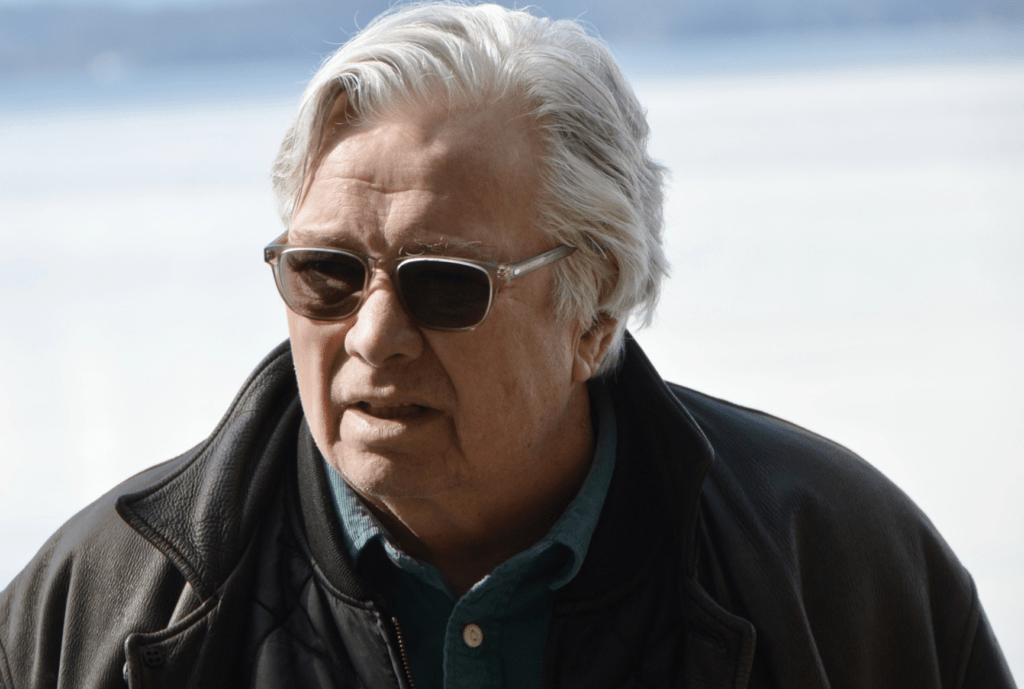

by Bruce McLellan

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2023

$32.00 / 9781771605656

Reviewed by Steven Brown

*

In a career spanning more than forty years of research Bruce McLellan live trapped and sedated hundreds of bears placing GPS radio collars on them enabling him to track their movements and observe their habits. The majority of the bears he studied resided in the Flathead Valley in southeastern BC. That’s an unusual name. The author explains:

The name comes from the indigenous Peoples that lived there who were part of the great Salish Confederacy. Although now called Flatheads, these people did not have flat heads. But a few centuries ago, it was the custom of some people living towards the Pacific Coast to gradually pressure the skulls of some infants so they developed flattened or even wedge-shaped heads. So with simple confusion from translating both spoken and sign language among French and English speaking fur traders and the many indigenous languages, people living in this region ended up being called Flatheads even though their heads were not.

Grizzly Bear Science and the Art of Wilderness Life is McLellan’s memoir of his years in the Flathead. With the research aspects of this book the specialist in bear scholarship will feel right at home but there’s plenty of interest here for the general reader with a desire to know more about these great hairy creatures. Male grizzlies depending on the time of year can weigh in at 600 pounds (272 kilos) and even larger. There’s a lot to learn.

Grizzlies are doing all right. The Flathead Valley has the greatest concentration of grizzlies in North America outside of Alaska. Grizzlies are making a comeback in western Montana immediately south of Canada’s portion of the Flathead Valley and doing well in Yellowstone National Park which occupies parts of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho.

The bears. They’re out there. They’ll be taking that long snooze they take, hibernation. It’ll last three months, depending on the bear. The author actually crawled into bear dens containing hibernating bears to get a better idea of what was going on in there.

Some other things about bear hibernation. Dens are usually at higher elevations. A bear can find the entrance to a den it’s used before even when the area is covered in snow. Caves used as dens show evidence of having been used by many different bears over long periods, even centuries. Grizzly bear hibernation is shorter than in other mammals who hibernate. Male grizzlies will leave their dens earlier in spring than female grizzlies leave theirs. Pregnant female grizzlies will give birth to one pound (454g) cubs and without really waking from hibernation lick them clean and eat the afterbirth. The baby bears, usually two, occasionally three, with eyes and ears that aren’t yet open, make their way to one of their mother’s six teats, favoring the four on her chest area. The cubs make an odd “chuckling” sound.

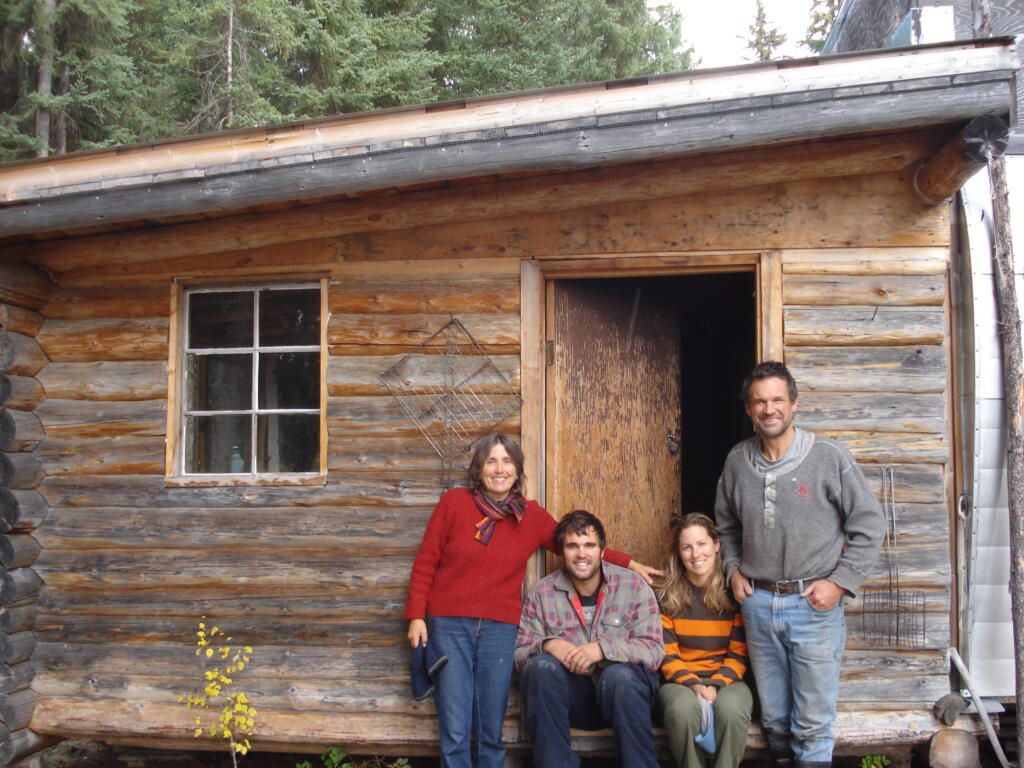

The 600 hundred square miles (1554 square kilometres) of the Flathead Valley is the largest uninhabited valley in southern Canada, which helps explain the rich diversity of animal and plant life within its confines. The author worked for months at a time in both summer and winter from a 1940s era cabin originally built by two game wardens along the east bank of the Flathead River flowing through the valley close to the US border. The Flathead River is a tributary of the Columbia River and winds its way south from BC into Montana. An extraordinary thing about these long sojourns in the wilderness is that Bruce McLellan had his family with him, his wife and their two children, a boy and a girl, from the time the kids were barely out of diapers.

The initial trip to the cabin with two young children took place in winter. As forest roads were impassable the 50 mile (80.46 kilometres) trip was accomplished on an aged snowmobile towing a toboggan of supplies including fuel. Enamoured of the outdoors from an early age, the author developed into a resourceful and highly skilled outdoorsman. Occasionally he hunted to supplement the cabin diet. Field dressing an elk is an important skill in the back country. Mechanical skills were also required to keep that snowmobile running as well as the older vehicles used to get back and forth from the nearest towns in season, Cranbrook or Fernie. He needed to know something about building because he put an addition on the original cabin. He was a skilled skier and dedicated to hiking sometimes long distances to get to where one of his collared bears was, doing its bear things. Then there was the patience required to sit quietly for sustained periods observing bear behaviour. Celine, his wife, accompanied him frequently. Eventually it became a family affair.

Some bears were studied from birth into their adult years, if the bear made it. Cub mortality is typically high. Hunting grizzly bears in BC was outlawed in 2017 but grizzlies still get shot. Many of the bears collared and studied wound up being shot by hunters, often, in the author’s experience, under dubious circumstances. Most shot bears are found near roads. Roads that access wild country are therefore a hazard for bears. They have no predators. The main threat continues to be humans and habitat loss.

Many bears he got to know well. He gave names to them. Just a few: Blanche, Melony, Aggie, Mitch, Elspeth, Old Pete, George, Angelica. Melissa and her three cubs, Cindy, Sally, and Bill. He learned that like people bears are individuals with unique personalities.

Stable isotope ratios. Not something that bring grizzly bears immediately to mind but an advance on traditional scat analysis to learn what a bear has been eating and what portion of it is meat and what portion isn’t. It’s remarkable but through isotope analysis of a clump of a bear’s hair it can be determined what it has been eating during the period of the hair’s growth. The diet can be surprisingly varied. When one thinks grizzly bear it’s huge, sharp teeth, powerful jaws and long sharp front claws that may come to mind. Carnivore. Meat can be on the menu but grizzlies in the Flathead Valley eat the roots of a number of different types of vegetation, scratching them from the earth with those long front claws. Sweet vetch. Creamy pea vine. Glacier lily. Cow parsnip. And of course there’s the berries. Buffalo, soap, Saskatoon, and, especially, huckleberries. Grizzlies will also eat grass and even ants if there are enough of them. On the meat side small mammals are eaten whole. Grizzlies aren’t averse to eating black bears. Often they drive off another predator from its kill and have it for themselves. Wolves are a frequent victim of this kind of theft. Being grizzlies of the Southern Interior, salmon is not on the menu as it is with west coast grizzlies. Diet varies depending on the season and the availability of various types of food. Some female grizzly diets can be almost exclusively plant material.

Foraging theory. Ingestion rates. Foraging models and a bear’s range. Male grizzles will roam over a sizeable territory. A grizzly can find anything in its range without a map. The home ranges of female grizzlies are much smaller. Ranges will overlap. That doesn’t become an issue for a male grizzly except when it means competing with another male grizzly for a female during breeding season. Male grizzlies will kill a female’s cubs so that mating with her produces cubs that are his. Male grizzlies, however, take no part in raising cubs to the point where they can survive on their own. It’s their mother exclusively and they stick with her. As the author states, “Nature is anything but kind…”

Bruce McLellan authored or co-authored over a hundred research papers and earned a PhD in the course of his field studies. There’s a great deal on offer in this book. His story is remarkable.

*

“Books have ruined my life,” jokes Steven Brown. A professional in the book trade for years he’s managed to retain a deep and abiding passion for good books and first rate literature. He was born in Saskatchewan and grew up in Ontario and British Columbia. Vancouver is home these days. His reviews have appeared in Canadian newspapers, a literary review or two and he has donated reviews to good causes. Editor’s note: Steven recently reviewed books by Gail Anderson-Dargatz, Patrik Sampler, Taslim Burkowicz, and Rhonda Waterfall.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Broadening our thinking on grizzlies”