1910 What’s in a name?

Canada’s Place Names & How to Change Them

by Lauren Beck

Montreal: Concordia University Press, 2022

$34.95 / 9781988111391

Reviewed by Jeff Oliver

*

Is it possible to read a nation’s history through its place names? Lauren Beck’s new book Canada’s Place Names & How to Change Them makes a compelling case for it. This is partly the story of the historical emergence of the place nomenclature the contemporary map of Canada has inherited, one that reflects, in significant measure, legacies of colonialism and patriarchy. But it’s also a guide, capturing the zeitgeist of decolonisation, for how to propose a place ecumene which respects the varied cultures and identities that have made their mark on Canada today.

Is it possible to read a nation’s history through its place names? Lauren Beck’s new book Canada’s Place Names & How to Change Them makes a compelling case for it. This is partly the story of the historical emergence of the place nomenclature the contemporary map of Canada has inherited, one that reflects, in significant measure, legacies of colonialism and patriarchy. But it’s also a guide, capturing the zeitgeist of decolonisation, for how to propose a place ecumene which respects the varied cultures and identities that have made their mark on Canada today.

Canada’s place names have complex roots. The most visible stem from a history of settler “invasion” that has tempered the map we are familiar with. English and French prevail, but digging beneath the surface of official maps reveals a richer multicultural and historical place nomenclature. Drawing on oral histories gleaned through anthropological texts, Beck, a professor of visual culture at Mount Alison University, introduces the reader to a rich, but little known, indigenous geography bound up with what she calls “place knowledge”, a living body of wisdom that buttresses the cultural geography of first peoples. Much of that knowledge emerges through a “human-centred” experience of the world that speaks to the capabilities of landscape for wayfinding, food getting and for revealing aspects of indigenous history and cosmology. The Tl’azt’en place name Chuz tizdli, in Northern British Columbia, forms the outlet of Chuzghun/Tezzeron Lake, at the location where its placid waters transform into the running current of Kuzkwa River. More than just a label for a dot on the map, place knowledge is implicated with environmental awareness that waterfowl nest along the shoreline because the running waters keeps it from freezing. Other indigenous places names speak to the origins of the contemporary world. For the Blackfoot in Southern Alberta and Montana the “Sweet Grass Hills” are an important landmark, crisscrossed by pathways and stories laid down by ancestors during the bison hunt. Most importantly, as a picture book for Blackfoot youth explains: “Old Man Napi, he carried rocks with him. He created the Sweet Grass Hills”, making this also a sacred place resonant with world building.

Layered on top of this indigenous geography is the map of Canada that we are more familiar with today. If the indigenous place names emanate from a deep history of experience in the landscape, “settler” naming practices, a group that lumps together everyone else, Beck tells us, are comparatively “superficial”. European naming practices begin with the premise that, because indigenous residents demonstrated no significant settlements or indications of agriculture (i.e. signs of civilization), the landscape of Canada formed a terra nullius open for the taking. Drawing on a well-established scholarship of critical cartography going back to J.B. Harley and David Woodward, she shows us how European map making and its associated colonialist bureaucracy proceeded not only to remake geography it its own image, but also to silence indigenous place ecumene and to reframe it through colonial eyes.

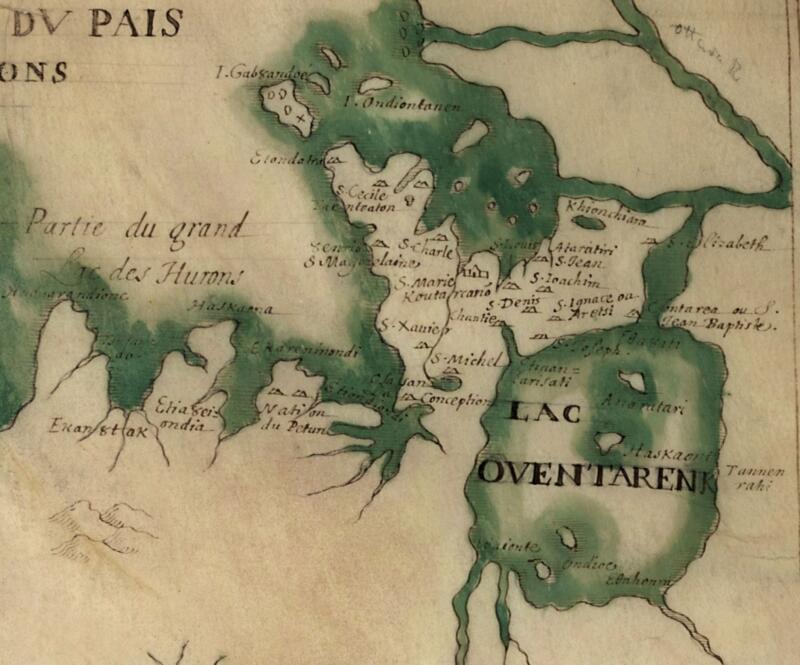

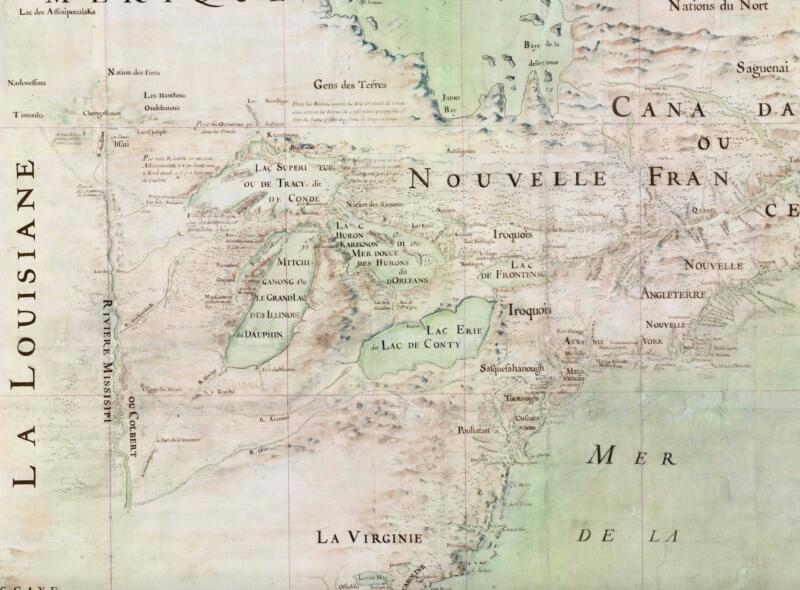

A study of Champlain’s map of “Nouvelle France” (New France) illustrates how European naming practices branded geography with names that brought newly “discovered” land within the cultural clutches of Empire. Catholic saints were forefront in the mentality of place making; so were names that spoke to the vanity of explorers, and especially their sponsors. For example, Cap de Potrinicourt (present day Minus Bay Nova Scotia) was named to flatter one of Champlain’s financial backers. Names that alluded to developments in scientific objectivity, a form of geographical absolutism that laid geography bare, were particularly important: Ill des Mont Desertz (Mount Desert Island, Maine) served to elevate the physical conditions of the island above all other knowledge claims. Beck suggests that later “Euro-settler” motivations for naming spoke to their interests in “trade and resource extraction”. Coppermine River in the Northwest Territories reflected the English explorer and fur trader Samuel Hearne’s hopes of locating the valuable ore in the most northerly reaches of the continent. Later in the twentieth century, towns founded on prising valuable minerals, like Asbestos, Quebec, boasted their way into the Canadian consciousness through toponyms that celebrated their material significance to the nation. Beck emphasizes how such naming practices emanate from the grasping agenda of a “colonial project”, questioning a “western condition” empowered to assign new names over old. That colonialism dispossessed is not in question, but historians and anthropologists may wish for more nuance here in what Beck glosses as an overly simplified history between natives and newcomers. European entanglements with indigenous Americans cannot be solely understood through the lens of colonialism and nor can their naming practices. Take the case of fur traders. Through mutually beneficial ties of marriage with local indigenous groups, many were entwined within complex cross-cultural kinship networks. What is more, they are known to have actively lobbied against the opening of areas to settlers because it interfered with social and economic networks they had fostered. Using their monopoly, the Hudson’s Bay Company managed to hold up settlement schemes in what became British Columbia until the second half of the 19th century. A similar messiness must be attributed to the long durée of Indigenous history prior to European contact. In that context the spread, displacement and/ or transformation of people and languages (and presumably their place knowledge) through their own interactions was the norm. A well-known example is the Northern Athabascan migration to the Northwest Coast, the Great Plains region and the American Southwest around a thousand years ago, a deep history Beck appears to be unaware of.

Settler place names not only signified cultural conquest, they also betrayed a gendered way of seeing rooted in patriarchy. An investigation of Quebec’s place name database reveals 10,000 names for male saints, nearly 80% of the total. Surveying the wider landscape, Beck reveals a history of place naming that is overwhelmingly white and male, with a small number of these leaving a disproportionate mark on the landscape: 134 places across the country bear the name John A MacDonald, the first prime minister of Canada. Unsurprisingly, places connected to female settlers are few and far between. At the same time that women were beging marginalized through toponomy, the male gaze rendered the landscape as female. Place names like Eskimo Paps (Newfoundland) attest to how the conquest of a feminized nature could also be sexualized. What is more, the linguistic dominance of English and French have limited older, gendered understandings of indigenous place names, which have been completely lost on the modern map.

Canada’s place nomenclature is anything but static. In what is one of the books more important contributions, Beck digs into the history of place name changes to reveal how galvanized protest can upturn toponyms shown to be anachronistic. Anti-German sentiment following the start of WWI resulted in Berlin, Ontario, a predominantly German speaking community, being renamed Kitchener, in honour of the decorated Field Marshal, war hero and colonial administrator. Chinaman Lake, added to British Columbia’s archive of place names in 1928, was replaced by Chunaman Lake in 2001, after John Chunamun, a chief of the Dane-zaa First Nations, when the Vancouver Association of Chinese Canadians pointed out its racist origins. Historical examples like these provide the primer for what must be Beck’s most original and controversial contribution.

Beck is not only a scholar of place names, she is also an activist for changing them. Given that Canada’s place names have been largely shaped by the masculinist ideologies of settler colonialism, a central argument is that the map should reflect the complex cultural and social identities that make up the modern nation. The balance of the book provides a thoughtful series of guidelines for doing just that, especially for those names that Beck defines as “problematic”. Particular attention is reserved for indigenous place names that have been “appropriated” by colonial authors. Moreover, she argues, place names with “pseudo-indigenous” origins, such as the names of four of Canada’s provinces (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec), are “abused” when handled and projected onto geographies away from the communities who speak them. Similar criticism is levelled at the misuse of the names of First Nations communities that do not adopt the embraced orthography or permission for their use. One example is the common use of colonial spellings of Micmac or Mic Mac in street names or commercial centres, rather than the currently accepted Mi’kmaq. Beck’s analysis is important for unsettling the assumed stability and inevitability of the contemporary cultural geography of Canada, which mostly goes unquestioned. But I don’t always share her view that swapping “colonial” names for those that authentically evoke indigeneity (along with their currently accepted orthography) is necessarily the solution. This is because in many parts of Canada, First Nations have become enmeshed with the cultures and languages of settler communities; some of which have lived alongside one another for hundreds of years. In so doing, they have reinvented what it means to be indigenous, which among other things can include the use of English or French as a first language. Indeed, they are as susceptible to the same nostalgia that other Canadians can be in thrall to. Beck’s own research confirms the possibility that this is so, particularly among older constituencies, reflecting more recent anthropological learning that colonialism is not only destructive but is also creative of new ways of being and identifying. Recognizing this point opens up further questions that remain unanswered. Who defines what is “problematic”? Beck is clear and open about what she thinks is, but presents little evidence about what other communities feel. With her unabashedly presentist viewpoint, Beck believes that too many of these names are oppressive. This is where her arguments get caught up in a less convincing binary of “origin cultures” in which too often settler = alien/bad and indigenous = authentic/good. While this might go down well on university campuses, especially among a literati engaged in the decolonial Twittersphere, the reality is surely more complicated.

Regardless of whether you agree or disagree with Beck’s views on revising Canada’s current place nomenclature, she is in this for the long game. Raising awareness and education on what could be is part of her message. For those who have taken the plunge, or are thinking about proposing a name change, she offers us some useful guidelines and interesting historical examples.

Few provincial or urban authorities have established policies for changing place names, but some have done. Beck takes a variety of examples to establish a more open engagement, building on policies that promote more inclusive naming, one that local communities can get behind. Any form of consultation must reach beyond figures of power, like mayors, chiefs and donors, who may reflect the established hegemony. Democratic processes are key. For example, New Brunswick requires a plebiscite in which over 50 percent of the local population must vote for the change. Tellingly, many of the instances of change she mentions come from university settings (there is now one less place honouring John A MacDonald – also author of Canada’s infamous indigenous residential school system). Outside these settings, her evidence is patchier (but see Asbestos Quebec, which was recently renamed ‘Val de Source’). While nostalgia is a powerful force for maintaining the status quo, especially among older age groups, Beck suggests that the introduction of multiple names for single locations can allow places to “grow” beyond the names we are accustomed to. Echoing the reality of indigenous cultural geography where “a place may possess more than one name in more than one language”, this innovation could provide citizens with choices about which name they wish to use. And over the long term, it “will graft one or more names onto our collective identity”.

Beck’s words end on a prophetic note. The place nomenclature of Canada has and will continue to change. Whether names stick will depend on how open we are to change, which is why education matters. Growing up in Coastal British Columbia, I once looked out on to the Strait of Georgia (named by Royal Navy captain George Vancouver to honour King George III), a place name for a narrow body of water separating the eponymous Vancouver Island from the North American mainland. Of late, another name has taken hold: The Salish Sea. Initially proposed in the 1980s and championed more recently in recognition of the indigenous Coast Salish lands that surround the Straight and the adjacent bodies of water between the US and Canada, the name was accepted by the Washington State Board on Geographic Names in 2009 and the British Columbia Geographical Names Office in 2010. It now frequently appears on official maps, including Google Earth. How will this watery margin be identified in the future? According to a survey published in 2019 by the Puget Sound Institute, only 15% of British Columbia’s residents and 9% of those from Washington could name and correctly identify the Salish Sea. But as Beck might argue, it’s still early days. I texted my sister whose home overlooks the Salish Sea if she was aware of the name: I know what it is,” she replied. “It’s the Georgia Strait renamed”

*

Jeff Oliver is a landscape archaeologist with an interest in the recent past. He writes on material histories of colonization and the cultural and environmental strategies of settlers in both Western Canada and Scotland. He is the author of Landscapes and Social Transformations on the Northwest Coast: Colonial Encounters in the Fraser Valley (University of Arizona Press, 2010). Born and raised in the Lower Mainland, he teaches archaeology at the University of Aberdeen. [Editor’s Note: Jeff Oliver has previously reviewed a book by Chad Reimer for The British Columbia Review]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1910 What’s in a name?”