1824 Hello, Wells

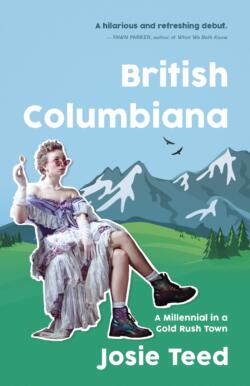

British Columbiana: A Millennial in a Gold Rush Town

by Josie Teed

Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2023

$22.99 / 9781459750210

Reviewed by Forrest Pass

*

The summer that I was eight, my parents bought me a red Walkman in hopes that it would keep me entertained during the long drive up to Barkerville, the reconstructed Cariboo gold rush town and that year’s family vacation destination. I also got to choose a tape to go with it, and from the modest offerings of the Sechelt Pharmasave’s cassette carousel, I selected a compilation of Country Hits of the Sixties. Whether my untrained ear was at fault or the quality of the analog recording, I thought that the Faron Young track Hello Walls was, in fact, entitled “Hello Wells,” and imagined it to be a homage to Barkerville’s newer, slightly shabbier — but also more recently lived-in — twin town. For a child of the 1980s (an “xennial” in the parlance of our times), travelling to a “living” gold-rush town that was then already more than a century old, this confusion of space and time made perfect sense.

The summer that I was eight, my parents bought me a red Walkman in hopes that it would keep me entertained during the long drive up to Barkerville, the reconstructed Cariboo gold rush town and that year’s family vacation destination. I also got to choose a tape to go with it, and from the modest offerings of the Sechelt Pharmasave’s cassette carousel, I selected a compilation of Country Hits of the Sixties. Whether my untrained ear was at fault or the quality of the analog recording, I thought that the Faron Young track Hello Walls was, in fact, entitled “Hello Wells,” and imagined it to be a homage to Barkerville’s newer, slightly shabbier — but also more recently lived-in — twin town. For a child of the 1980s (an “xennial” in the parlance of our times), travelling to a “living” gold-rush town that was then already more than a century old, this confusion of space and time made perfect sense.

As I read British Columbiana, Josie Teed’s frank and amusing memoir of a year spent living in Wells while working as a curatorial assistant and costumed interpreter at Barkerville Historic Town, I felt a certain solidarity — the historical theorist E.H. Carr might say “imaginative understanding” — with the author as she drives through the Cariboo for the first time, listening to a playlist of “40s Country,” music about a generation older than the soundtrack to my first Barkerville visit. Teed fancies that she is preparing for her role by listening to the singers’ long-dead voices, and in a sense her thinking is not entirely anachronistic. After all, the timelessness of living history sites is illusory. In the great scheme of human history, the period that Barkerville presents is rather recent. The children who scratched cursive letters into slates in Barkerville’s one-room school easily could have listened, as octogenarians, to 40s Country. Moreover, the version of the Cariboo gold rush that Barkerville offers its visitors is really a dialogue between what researchers have gleaned from the written and material records of the period and the experiences, expectations, and values of later residents, interpreters and visitors. For each generation, a day (or a year) spent in Barkerville will mean something a little different.

Separated from us by only a few generations, Barkerville’s nineteenth-century residents lived lives similar enough to our own for us to come to an imaginative understanding, but just far enough removed to seem a little unfamiliar. Readers “d’un certain âge” might feel a similar tension between the accessible and the mildly foreign as they see Barkerville and Wells through Teed’s eyes. The title promises the experiences of “a millennial in a gold rush town” and Teed delivers. Her generational lens verges at times on the stereotypical, as when she remarks that Wells’ tarp-covered wood piles “made for quaint Instagram posts,” or when she considers a selfie in her volunteer fire-fighting kit might work as a pic for an online dating profile. She also clashes with older colleagues over what she perceives as their casual racism or homophobia, and even over the question of removing statues of controversial historical figures — all typically intergenerational flashpoints. But Teed shows none of the entitlement that some might consider a hallmark of her generation. Appointments with her Quesnel-based therapist punctuate the narrative, and she is frank about her insecurities, both professional and interpersonal. Her self-deprecation is often very funny: I laughed out loud, for example, at her description of breaking out in acne from the exertion of writing, and at her frustration at having warranted the attentions of a man in a poncho.

Teed’s self-deprecation might make it easier for Wells residents to accept the candid and occasionally unflattering depictions of them. The book reminded me a little of David Farley’s An Irreverent Curiosity, which, like British Columbiana, humourously recounts its author’s sojourn in a small town steeped in history and populated by eccentrics. Farley, who was separated from his subjects by distance, time, and a language barrier, may have found a limited readership among residents of Calcata, a medieval Italian village whose parish church purportedly preserves the desiccated foreskin of Jesus Christ. For her part, Teed can be sure of a large audience among Wellsites and Barkervillians. Names have been changed, but the disguising is perfunctory, and both Wells and public history in Canada are small communities. For instance, as I was reading British Columbiana, I had a hunch that Teed’s predecessor as curatorial assistant, who makes a brief appearance on page 32, might be a current coworker of mine whom I knew had worked at Barkerville some years ago. A surprised “Sita” (as Teed has rechristened her) confirmed her own identity and, over the course of a Friday afternoon MS Teams chat, recognized a few other characters based on Teed’s descriptions. Whether Teed’s former coworkers are flattered, offended, or a little of both at their appearance in her book, they are identifiable and, for better or for worse, immortalized.

I don’t mean to suggest that this book is just salacious gossip and early-twenty-something angst, though Teed does write about both of these entertainingly and sincerely. Museum folk rarely write tell-all memoirs and future museologists might read British Columbiana, especially its later chapters, for the snapshot it offers of life and labour in the Canadian heritage sector in the 2010s. Some of the details are practical: how a young millennial woman adapts to wearing a museum-issue corset; how vast collections of vintage bottles are at once too “historical” to dispose of and too “boring” to exhibit; and how an archivist teases a hurdy-gurdy girl’s story of love and redemption out of seemingly dull and dusty bureaucratic documents.

Other discussions are more philosophical. Teed’s fellow interpreters worry about the “Disneyfication” of history — a perennial concern for staff at many museums and historical sites — and Teed’s boss “Nancy” points out instances in which interpretation of the site departs from strict historical accuracy in the interests of visitor experience. Anyone who has worked in heritage will recognize in Teed’s description of Hallowe’en preparations the challenge of striking a balance between interpretation and revenue generation. Among Teed’s roommates, workplace rivals, and prospective love interests, I detect the peculiarity and precarity, passionate commitment and youthful transience that characterize so many young heritage workers. 2023 has already proven to be a difficult year for some of British Columbia’s provincially-owned but independently-managed heritage sites, with the closure of Point Ellice House for want of adequate government support and the controversial prospect of new management at Historic Yale. As the longtime “jewel” of the province’s heritage property portfolio, Barkerville may be spared some of this tumult, but reading between the lines of British Columbiana, we see that the town faces challenges common to many museums.

In the end, Teed finds that heritage interpretation is not for her. “All around me were ordinary people, fixed securely in the twenty-first century,” she writes of her fellow passengers on her flight home to Ontario. “Their concerns lay in the present, and the future. Mine should, too, I thought to myself.” It seems an odd note to end on, for it belies the more complicated relationship between past and present that underpins her book. British Columbiana is an engaging, funny, and at times deeply revelatory account of a year spent in a living museum. Teed’s decision to write it — to recount her own recent past and its connection to British Columbia’s slightly more distant one — suggests that she might find it difficult to say so securely, “Good-bye, Wells.”

*

Forrest Pass is a Curator in the Programs Division at Library and Archives Canada. His career path in the public history field has included researching gold rush artifacts for a national museum and developing exhibits (and hanging Christmas lights) at a heritage village. Originally from the Sunshine Coast, he now lives in Gatineau, Quebec. Editor’s note: Forrest Pass has recently reviewed books by Robert A.J. McDonald, Richard Kool & Robert A. Cannings, Moira Dann, Hannah Turner, Maddie Leach & Michael Kluckner, and Philippe Tortell, Mark Turin, & Margot Young for The British Columbia Review.

Forrest Pass is a Curator in the Programs Division at Library and Archives Canada. His career path in the public history field has included researching gold rush artifacts for a national museum and developing exhibits (and hanging Christmas lights) at a heritage village. Originally from the Sunshine Coast, he now lives in Gatineau, Quebec. Editor’s note: Forrest Pass has recently reviewed books by Robert A.J. McDonald, Richard Kool & Robert A. Cannings, Moira Dann, Hannah Turner, Maddie Leach & Michael Kluckner, and Philippe Tortell, Mark Turin, & Margot Young for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster