1805 Nêhiyawêwin: being Cree

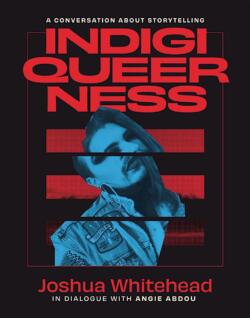

Indigiqueerness: A Conversation About Storytelling

by Joshua Whitehead, in dialogue with Angie Abdou

Athabasca, Alberta: Athabasca University Press, 2023

$19.99 / 9781771993913

Reviewed by Mary Ann Moore

*

Joshua Whitehead doesn’t feel ashamed writing about sex he says. When he went home to “the rez,” he’d prefer helping the women in the kitchen where all the liveliness was rather than watching TV in the living room with the men.

Joshua Whitehead doesn’t feel ashamed writing about sex he says. When he went home to “the rez,” he’d prefer helping the women in the kitchen where all the liveliness was rather than watching TV in the living room with the men.

Whitehead’s aunties, mother and grandmother were loud, energetic and animated, laughing, in the case of his aunts, about who they “snagged (or slept with)” the weekend before.

“These conversations were just so normal that the idea of sex was simply a part of our lives, not something to be ashamed of. It’s part of our Cree culture,” Whitehead says in Indigiqueerness, written after a conversation with Angie Abdou.

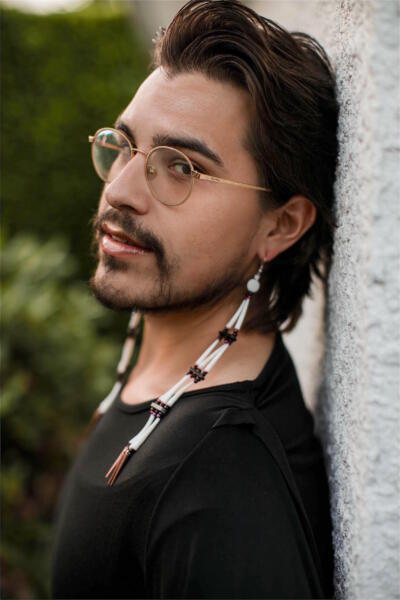

Joshua Whitehead is an Oji-Cree/nehiyaw, Two-Spirit/ Indigiqueer member of Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1).

Included with the definitions in the book, featuring colourful photo montages, is Nêhiyawêwin meaning “being Cree” with the root word, neyihaw, meaning “an Aboriginal person.”

“Two-Spirit is an Indigenous term for those who may be seen, from within Western epistemologies, as not conforming to ideological ideas of gender, sex, sexuality, and/or communal roles” as Whitehead describes the term, often represented as 2S following LGBTQ.

“Inclusive” is the word repeated in his definition of “Two-Spirit” such as “sexuality (inclusive of LGBTQ+) “ . . . Two Spirit people [are] at the forefront of decolonizing Indigenous sexualities through language and ceremonial revitalization and/or land/water protective activism . . . “

The definition in the book, really an art object, goes on to say that language “needs to mutate and change. Hence Indigiqueer. Hence, not knowing and knowing. That’s the whole damn point to me. That’s the whole futuristic key of Indigenous sexual, and by elation, environmental sovereignty because to be undefinable is to be unknowable to colonial powers – that’s radical freedom. In my opinion, at least.”

A quote in larger letters is: “I discovered myself as I removed myself from the world.”

Storyteller Whitehead admits that it’s “incredibly embarrassing” when doing a reading in his hometown with his family present and he’s talking about “fun sex acts that queerness involves.”

As mentioned earlier, sex is part of his Cree culture. As Whitehead says in response to Angie Abdou’s question in which she gets the feeling he likes writing about sex, he says: “Even in our trickster stories, we have detachable genitalia and mountains that become breasts and rivers as vulva, sex and sexuality – hetero sex and sexuality that is – were naturalized and normalized.”

Jonny Appleseed (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018), Whitehead’s bestselling novel that was the winner of Canada Reads in 2021, is about a queer character, also from Peguis First Nation. “I wanted him to be unabashed. I am (and my community is) unabashed about sexuality. I didn’t want to shy away from raunchiness and messiness,” Whitehead says of the book that people often believe is a memoir.

He writes of his character at the end of Jonny Appleseed: “Jonny has taught me a lot of things but there are two that I want to share with you: one, a good story is always a healing ceremony, we recuperate, re-member, and rejuvenate those we storytell into the world; and two, if we animate our pain, it becomes something we can make love to.”

Angie Abdou, who holds a Ph.D. in Creative Writing from the University of Calgary and has published seven books, poses the questions in Indigiqueerness, presented in a countdown from 10 to 1. The first is (i.e. Number 10): “What were you like as a child and when did writing and reading become important in your life?”

He has always gravitated toward books and writing, Whitehead says. His parents still have a stack of poetry and prose he wrote when he was around five or six years old. And Whitehead notes, he’s always been obsessed with apocalypses.

He grew up in Selkirk, Manitoba and spent summers in Peguis First Nation. The family was poor, living in housing projects “in a town very much segregated between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.”

At school, Whitehead “excelled” in home economics. In a Zoom interview with Angie Abdou, one of the Learning with Syeyutsus presentations, an initiative of Nanaimo Ladysmith Public Schools in partnership with UBC Press, Whitehead described himself as a queer kid who had Michael Jackson dance parties and dressed up as Sailor Moon.

While back at home and isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, Whitehead was “emotionally and mentally exhausted from the memory excavations I had to do for Making Love with the Land (Knopf Canada, 2022), my memoir about mental health.”

He read earlier writing about the characters he created as a teen and remembered he loved them and still thinks about them. “Characters can live within us for so long,” he says, “not like a parasite but like a host. They fatten and become emboldened and return to us when we need them down the line. That’s what Jonny did for me in Jonny Appleseed, and these characters are doing that again.”

Growing up shy and now working on stages with large audiences “blows child Josh’s mind,” Whitehead says. He began finding confidence in his own writing voice toward the end of high school when he started attending writing workshops. “I knew my strongest most stalwart ability as a person was being a storyteller. It’s persona work, like theatre.”

The ”gritty artistry of Winnipeg” was formative in his early twenties as he started to become a writer and his novel, Jonny Appleseed is very much infused with it.

Whitehead did his undergraduate degree in English Honours at the University of Winnipeg. He’s now also completed his Ph.D.

“A lot of my material comes from listening fiercely to those around me and witnessing that which is discarded or not seen.” A definition is included in the book of the term “witness” from the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Part of the definition reads: “Generally speaking, witnesses are called to be the keepers of history when an event of historic significance occurs.”

“Animations are the backbone to Nêhiyawêwin (or Cree) as we don’t have genders, we instead animate things (including rocks, sky, mountains, earth, the non-human) and in animating them we are in relation. What I mean here is, I animate my kin/relations, and listen to them, that’s where stories begin,” Whitehead says.

Answering Abdou’s question about Jonny [Appleseed] needing his own book, Whitehead replies: “Every rez probably has a couple Jonnies on it.”

In his book, Jonny Appleseed, Whitehead wanted to ask: “What about queerness outside of those queer urban ‘utopias’ “such as Los Angeles, Vancouver, New York, San Francisco?”

“I wanted to show we can thrive in our own homes. We don’t have to flee or migrate to cities and abandon part of our identities. We can be Indigenous and we can be queer and we can be rural – all at the same time.”

As for reading, Whitehead says it “is a very collaborative endeavour.” He includes Cree language in his writing without much explanation, he says.

“The role of translation,” he says, “specifically for Indigenous languages, does a disservice. In Cree, to translate “tânsi” to “hello” . . . well, it does mean that, but it’s also asking how you are and how you have been and sometimes where you’re from. Those things get lost if we offer a direct translation. Depending on the conjunctions or inflections, the meaning of the word changes.”

One of Abdou’s last questions is about Whitehead’s “roles as writer versus professor, or creative person versus academic person, or artist versus employee.”

Whitehead, who is an Assistant Professor of English and Indigenous Studies at the University of Calgary (Treaty 7), says: “Academic theory is a type of poetry, but a poetry that is trying too hard to sound like poetry, to the point it becomes obtuse. I try to read theory like poetry (even though academics themselves insist on a hard division between creative and critical work).

“I take it as my job to eat these theories – eat gender theory and queer theory and decolonial theory and post-colonial theory – and dissolve it all in my belly and spew it onto the page as fiction and poetry and nonfiction. That’s more accessible.

“When philosophy becomes story, it becomes the greatest tool we can use for societal reformation.”

While storytelling is a living, breathing art form, we can also be grateful for the tactile work of art with colourful pages of quotes and photo montages that is Indigiqueerness. The cover, art direction, and illustrations are by Brnesh Berhe. The interior book design is by Natalie Olsen.

Reading Indigiqueerness, you’ll be inspired to read more of Joshua Whitehead’s work as well as other Indigenous writers “defying the expectations of border.”

*

Mary Ann Moore is a poet, writer and writing mentor who lives on the unceded lands of the Snuneymuxw First Nation in Nanaimo. Her full-length book of poetry is Fishing for Mermaids (Leaf Press, 2014) and she has a new chapbook of poems called Mending (house of appleton). Moore leads writing circles and has two writing resources: Writing to Map Your Spiritual Journey (International Association for Journal Writing) and Writing Home: A Whole Life Practice (Flying Mermaids Studio). She writes a blog here. Editor’s note: Mary Ann Moore has also reviewed books by Donna McCart Sharkey & Arleen Paré, Michelle Poirier Brown, and Celia Haig-Brown, Garry Gottfriedson, Randy Fred, & the KIRS Survivors for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-24: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster