1774 Hardwired for defiance

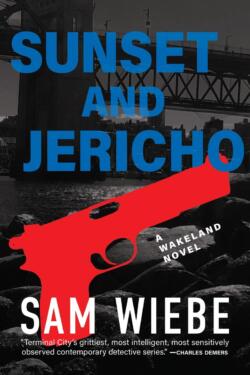

Sunset and Jericho: A Wakeland Novel

by Sam Wiebe

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2023

$24.95 / 9781990776236

Reviewed by Brett Josef Grubisic

*

Regarding Sunset and Jericho, an expected question might be “So, is it any good?” Happily, the unhesitant answer (“Yes, absolutely”) inspires a better follow-up: “Oh, what’s so worthwhile?”

Regarding Sunset and Jericho, an expected question might be “So, is it any good?” Happily, the unhesitant answer (“Yes, absolutely”) inspires a better follow-up: “Oh, what’s so worthwhile?”

The easy reply is “New Westminster’s Sam Wiebe.” This author’s tough, wounded, and increasingly embittered character (Dave Wakeland) ought to be a household name.

Narrated by Wakeland, wintry Sunset and Jericho showcases punchy, rhythmic dialogue spoken by difficult, intriguing, compromised, and occasionally terrifying characters whose motivations and actions (from ignoring overdue bills to dousing a corpse in bleach) coalesce into a colourful and gripping portrait of humanity and the unbalanced, volatile society it has created.

Society, in the case of Sunset and Jericho, is Vancouver, a city — “Cold and unaffordable, but now mean in a way it hadn’t been” — of heaving, breakneck changes. Wakeland’s astonished by it over and again. Both “hardwired for defiance” and driven to understand the puzzles he encounters, Wakeland is confounded by the place, his role in it, and the necessary steps to make it better. Either a wary romantic or reluctantly sentimental, Wiebe’s dogged Private Investigator yearns for earlier iterations of the city, when ordinary folk weren’t priced out of the market; for Wakeland, the past is the place where the entitlement and extravagances of the monied elite weren’t so visible, so accepted, and so adulated.

Wiebe also captivates with a dazzling criminal case that initially inspires Wakeland to halfhearted action. There’s a missing person (the mayor’s partying brother, in fact). The second, a nearly hopeless commission, involves a stolen object: Wakeland is hired by a distressed transit guard whose face was scalded by “jailhouse napalm” during the assault where assailants got away with her handgun.

Ostensibly unrelated, Wakeland’s cases eventually lead him all over the GVRD. Intricately interwoven (not to mention progressively bloody and perilous), Wakeland’s pursuits impact his physical health and mental wellbeing. As battle-weary Wakeland trudges through the costly homes and panelled offices of Vancouver’s movers and shakers — “crooks with unlimited funds,” “princelings,” and one “phoney mystic” — and speaks begrudgingly to careerist politicians and patrician real estate developers, he grows reflective about his unwelcoming hometown as well as his own capacities — for violence, for love, for endurance, for hope.

After ten years as a PI, the experiences of this former cop have battered and transformed him; and if he’s cynical, despairing, or pushed to his moral limits in Sunset and Jericho, there’s ample evidence to situate those states of mind in his everyday interactions. Often, for Wakeland, other people are hell.

*

To begin, though, there’s Wiebe’s writing. Elegant but unfussy and poetic without growing gnomic or precious, Wakeland’s narration compels us to listen to his weary voice and see through his wizened eyes. From “Just fucking watch me,” the last words of the novel, to the opening paragraph, he’s magnetic. And Wiebe’s short exhilarating chapters (78 in Sunset and Jericho) perfectly complement Wakeland’s clipped delivery. He can quip, exhort, describe, and philosophize but he’s always economical. He says what he needs to say, and not a whole lot more.

As tough, pithy, direct, and feral as Wakeland can be, he possesses a subtle eye that’s unexpectedly attuned to beauty. So, while Sunset and Jericho has no shortage of viscerally-described wounds and dead bodies (and fights: “Beyond thought. Beyond even desperation. My broken fingers felt someone’s hair. A neck, a face. I brought mine closer. Sank my teeth into soft jelly. Heard a scream and held on, gagging at the wash of fluid, the ropy fiber of an eyelash”), Wiebe counterbalances this occupational brutality with “something,” as Wakeland exclaims, whether a mood, sight, or moment:

The view from the mayor’s outer office was something. Pearl-coloured clouds had flung down snow all night, piling slim white barriers atop Vancouver’s roofs and awnings. A late morning rain was undoing the work, drowning Broadway in a slurry of gunmetal, platinum and ash. On Cambie Street, caution lights pulsed. An accident of some sort. It was February, and the wrong people were dying.

Even within that paragraph (the novel’s opener), the sublimity of the view steadily erodes; the panoramic beauty — snowfall from pearlescent clouds — cedes to “drowning,” “slurry,” “ash,” “caution lights,” and “dying.” The world, the urban world, that is, can never leave well enough alone. It intrudes and insinuates itself into every street and address.

Wakeland meets dark souls as his labyrinth of a case twists and turns and twists again. Callous, maniacal, self-serving, fanatical, entitled, deluded, lost, and hateful, Wiebe’s characters come across as opposite sides of the same coin. Wakeland notices as much and proceeds with the job in a state of deep reluctance. If the novel’s cadre of villains uses senseless violence to (supposedly) achieve societal betterment and the 1 percent uses its status to maintain a status quo that’s offensive to Wakeland, then what good is he doing as a gun-for-hire?

“I want to understand,” Wakeland states in assorted ways as Sunset and Jericho progresses. Optimally, understanding promotes enlightenment. With this disposition, however, Wakeland faces a quandary: what if this drive — for answers, for clarity, for truth — leads to unwanted or undesirable results? If home is a terrible place, or its citizens are, or, more generally, if the human species is just bad to the bone, then where does that leave Wiebe’s hero?

Wiebe realizes the value of a cliffhanger, and in Sunset and Jericho’s terminal words (“Just fucking watch me”) he’s crafted one that’s perfectly pitched. Without a doubt fans will stay tuned. We’ll wait for further news about the fate of Wakeland, a befuddled and earnest Everyman in a breathtakingly imperfect world.

*

My Two-Faced Luck, the fifth novel by Salt Spring Islander Brett Josef Grubisic, published in 2021 with Now or Never Publishing, is reviewed here by Geoffrey Morrison. A previous book, Oldness; or, the Last-Ditch Efforts of Marcus O (2018), was reviewed by Dustin Cole. Editor’s note: Brett Josef Grubisic has recently reviewed books by Joseph Kakwinokanasum, Chelene Knight, Lyndsie Bourgon, Gurjinder Basran, Don LePan, and Paul Headrick for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1774 Hardwired for defiance”